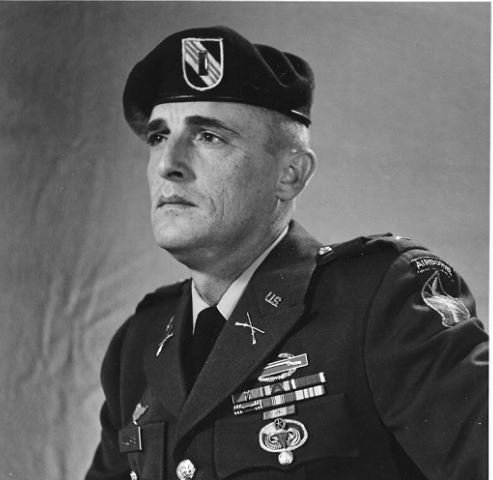

In a battle for the district capital of Phuc Long Province in the III Corps area about 60 miles northeast of Saigon in the country of Viet Nam, Special Forces 2LT Charles Q. Williams would distinguish himself in the battle of the Dong Xoai CIDG camp and later be awarded the Medal of Honor.

In the same action, CM3 Marvin Shields, Navy Seabee would posthumously be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions.

Dong Xoai was home to 400 Montagnard CIDG strikers and 24 US troops including Special Forces and Navy Seabees. On the dates of 9-10 June, the Viet Cong, with North Vietnamese Support attacked the base with 1500 guerrillas armed with AK-47s, grenades, rocket-propelled grenades, rocket launchers and flamethrowers.

The 14-hour battle would leave 20 of the Americans either killed or wounded along with 200 Vietnamese strikers and civilians. Vietcong dead numbered between 500-700.

Williams was the XO (Executive Officer) of the Special Forces A-Camp when the Vietcong began massing for an attack on the camp late on June 9. The Americans were aware of the buildup outside the camp and placed their troops on full alert.

This caused the Vietcong to begin their attack over an hour early, and at 2330 they began to mortar the camp, hitting both Vietnamese and US positions before an infantry assault by the 272nd Regiment.

It was during the initial artillery fire that the Special Forces commander of the camp was hit and seriously wounded which would place Williams in command of the camp. He wasn’t the typical 2LT. Williams had been an NCO in the 82nd Airborne Division before going to Special Forces and Officer Candidate School.

Williams organized his defenses in his compound and determined the source of the insurgents’ main effort and led the troops to their defensive positions on the south and west walls. The Vietcong initially took heavy casualties by failing to negotiate and recognizing the barbed wire and minefields that the team had laid out. Williams attempted to establish communications at the District Headquarters, found that there was no operational radio with which to communicate with his commanding officer in another compound.

Attempting to reach the other compound and establish communications, the heavy assault by the Vietcong drove him back and he was wounded by shrapnel in his right leg. He returned to District Headquarters and directed the defense against the Vietcong’s first attempted assault on the camp.

The Vietcong had succeeded in scaling the walls and as some of the strikers began to panic and retreat, Williams ran thru a hail of gunfire, and rallied the Montagnards, and led them back to their positions. He was wounded two more times in the left leg and thigh.

Told that communications were restored, he raced back to the communications bunker, where he sustained two more additional wounds in the stomach and right arm from grenade fragments. Then he was told that the detachment commander was seriously wounded and he was in overall command of the camp’s defenses.

The Vietcong stepped up the pressure and the camp defenses began to crumble. At 0130 two helicopter gunships from the Bien Hoa airbase expended all of their ammunition on the communist troops inside the wire.

With casualties mounting, Williams ordered the consolidation of the American personnel from both compounds to establish a defense in the district building. The Special Forces and Seabees from the SF compound would withdraw to the district headquarters and consolidate with the remaining CIDG troops.

Williams, despite his many wounds, grabbed a radio and was directing airstrikes thru a forward air controller all while directing the defense from the District building. Firing flares as reference points to adjust the air strikes with deadly precision. Williams’ defense force was now besieged and they were throwing grenades out the windows of the district HQs at the charging Vietcong.

By dawn, the Vietcong had the upper hand and were firing a machine gun directly south of the district building, pinning the Americans and strikers down in a murderous fire. The machine gun had to be taken out. Williams didn’t hesitate and led the mission himself.

He grabbed a 3.5-inch rocket launcher and asked for a volunteer to help him go after the gun. CM3 Marvin G. Shields, a member of the camp’s Seabees detachment stepped forward despite already having been wounded three times. Under heavy fire and completely ignoring their own safety, the two attacked, with Shields loading and Williams firing as they assaulted the enemy position. And despite a faulty sight, they destroyed the enemy gun from a distance of 150 meters.

While trying to return to the district HQs, both men were hit again, and Shields was seriously wounded where he would later die of his wounds the next day. Williams was unable to carry Shields back to the district building, he pulled him to a covered position and then made his way back to the HQs where he sought more volunteers who went out and successfully brought Shields back.

Vietcong attempts to take the district HQs building increased and were firing recoilless rifle fire directly into the American positions. Williams continued to direct air strikes on the communists and they were creeping increasingly closer almost on top of their position.

By early afternoon, and the situation deteriorating, he moved the seriously wounded to communications bunker. Informed that helicopters would be landing to exfil the Americans from the area, Williams led the team to the camp’s artillery positions. And finally, after evacuating all other wounded personnel, he boarded a helicopter and took the last Americans out.

The Vietnamese Rangers entered the battle but were ambushed by the Vietcong and broke. This prompted General Westmoreland to send a battalion of the 173rd Airborne Brigade into action. This was the first major involvement of large numbers of US troops in Vietnam.

Williams would receive his Medal of Honor from President Lyndon Johnson at the White House a year later in June 1966. Shields widow would receive his two months later in the Oval Office. In his remarks Johnson would say of Williams:

“We have come here this morning to honor a very brave American soldier.

The acts of extraordinary courage to which we pay tribute were not performed with any hope of reward. They began with a soldier doing his duty–but they went so far beyond the call of duty that they became a patriot’s gift to his country.

Lieutenant Williams and a very small band of Americans and Vietnamese fought for 14 long hours against an enemy that outnumbered them more than five to one.

During those long hours, Lieutenant Williams was wounded five times. Any single one of those wounds might have caused another man to completely abandon the fight. Yet Lieutenant Williams continued to rally his men, to protect his wounded, to hold off the enemy until help could come.

Few men understand what it really means to draw deep from the wellsprings of such bravery. Few have ever made that kind of journey–and far fewer have ever returned.”

“Lieutenant Williams, it is hard for your President to find words to tell you of the deep gratitude and admiration that your fellow Americans have for you.

But I do rejoice that I may present to you, in the name of the Congress of the United States and of the grateful people of America, the Medal of Honor–for the bravery and the gallantry that you displayed at the risk of your life, far above and beyond the call of duty.”

Williams retired as a Major and died in 1982 at the age of 49. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Photos courtesy, US Army, US Navy, YouTube

COMMENTS