At that time, Warsaw citizens had only hand guns, no anti-tank weapons, to defend themselves. The latter were replaced with petrol bombs (Molotov cocktails), anti-tank grenades and a few RPGs. Even though the morale and the willingness to fight and win were tremendous, the Uprising lasted for just 63 days of an uneven fight that ended in a fall.

When it was clear that the Warsaw Uprising wouldn’t finish very quickly, and its leaders supported the Allies, Stalin’s army became hostile. Although they were waiting at the gates of city from the end of July, it wasn’t until 14 September when the Red Army and the First Polish Army liberated Praga, situated on the eastern bank, that hadn’t taken part in the upraising.

The Soviet command allowed only smaller sub-units of the First Polish Army to be sent to battle, which in no way changed the fate of the Uprising. The Uprising Headquarters counted on air support from the West for weapon supplies and provisioning. On August 3, the President of the Polish Republic in exile, Wladyslaw Raczkiwicz, asked Churchill about it.

That very same day, the Mediterranean Allied Air Force stationed in Brindisi received a telegram from London ordering an air attack to the Poles fighting Warsaw. In the beginning, the aid provided only air drops in forests near Warsaw. However, the order was broken by Polish airmen from 1586 Special Duty Flight, who, during the night of August 4, flew over Warsaw.

The next day brought a total ban on flights over the city due to heavy losses in the initial missions. It took a lot of intervention from the side of the Polish Government in exile to allow Polish crews from 1586 Special Duty Flight to take part in “voluntary hazardous to Warsaw,” and everybody signed up.

On August 12, British and South African units were also allowed to take part in air-dropping provisions. For this mission, the 205 Group was chosen. It consisted of the 1586 Special Duty Flight, 178 and 148 squadrons of the Royal Air Force and 31 and 34 squadrons of the South African Air Force. The whole operation was more difficult due to the fact that Allied planes couldn’t land on the Soviet airfields on the right bank of the Vistula.

Those missions turned out to be one of the hardest missions in the history of Air Force. The Italian allied air bases in Brindisi were 1,500km from the Polish capital. Flights took, on average, 14 hours and at night, often in difficult weather conditions. The Special Duty Flight lost 11 planes with 59 soldiers during those missions, which constituted 150% of the total numbers.

The other squadrons lost 19 planes. 39 British, 37 South African and 12 American pilots were killed in what constituted 25% of losses. It wasn’t until September 10 that Stalin agreed to allow American and British planes to land in the areas controlled by the Red Army.

Thanks to that decision, on 18 September, the 8th American Air Force organized a mission over Warsaw during which 107 “Flying Fortresses” dropped nearly 1,250 pods with supplies (Operation Frantic 7). In the face of wide criticism though, the mission couldn’t end successfully, of course, or improve the dire situation.

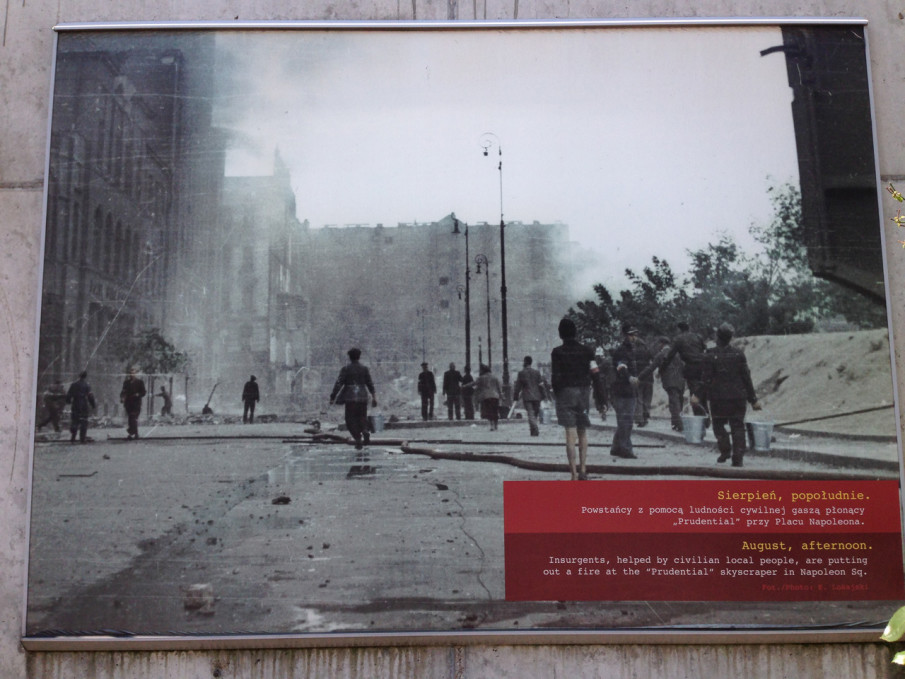

The Warsaw Uprising, although controversial, was inevitable. People en masse had been waiting impatiently to be able to fight in retaliation for five years of brutal occupation, and they fought a lonely fight for 63 days against the overwhelming forces of the German Army. The fight ended on October 3, 1994.

The Warsaw Uprising was one of the most important events in the modern history of Poland, and its consequences were far-reaching and they are still echoing today – the destruction of a significant part of the city, its historical sights, its infrastructure and, above all, the loss of thousands of young, educated people who gave their lives for their country.

Everyone who was in Warsaw on 1 August at 5 pm stopped for a minute, listened to the sirens and thanked the heroes.

Thanks for listening

Naval

(Photos Courtesy: Author’s Private Collection)

COMMENTS