Led by an MC-130 guideship, a formation of 6 helicopters would leave Thailand, fly across Laos and into North Vietnam at low level. Approaching the camp, another MC-130 would release flares as the helicopters prepared to land.

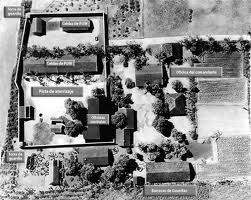

A ground force of 56 men commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Bud Sydnor Jr. would hit Son Tay. They consisted of an assault group of 14 men under Major Dick Meadows that would crash land inside the compound using an HH-3 Jolly Green Giant Helicopter. They were to engage any guards and rescue prisoners. 4 larger HH-53 Super JollyGreen Giant choppers would land in fields adjacent to the walls. One chopper carried a 22 man support force to aid the assault, while a second carried a 20 man security force to hold off enemy attempts to reach the camp. Sydnor and Simons would be a part of each of these teams respectively.

Once secured, prisoners would be led out to 2 more HH-53’s to be extracted. A lone HH-53 would stay airborne to provide gunship support with .30 caliber miniguns, while 2 prop driven AD-1 Skyraider attack aircraft would destroy bridges in the vicinity. Jet aircraft would provide combat air and SAM suppression patrols. Even the Navy would create a massive diversionary attack over Haiphong Harbor. However, due to the bombing halt, they were only to drop flares.

Receiving final approval from Nixon, the razor-honed force arrived at 3:00 A.M., November 19th, at Takli Air Force Base in Thailand, where Simons informed them of their target. “We are going to rescue 70 American prisoners of war, maybe more, from a camp called Son Tay. This is something American prisoners have a right to expect from their fellow soldiers. The target is 23 miles from Hanoi.”

First there was silence, and then the men rose as one and applauded. This reassured Simons they were ready and willing.

First there was silence, and then the men rose as one and applauded. This reassured Simons they were ready and willing.

After final gear checks and a trip to Udorn Air Force Base, close to the Laotian border, the olive drab attired and blackened face men transferred to the helos. and the ground force lifted into the darkness at 11:18 P.M. November 20th Thailand time for the 337 mile flight to Son Tay.

Flying in a V formation behind the MC-130, the force maneuvered at tree-top level through Laos and on into North Vietnam, penetrating the deadliest air defense system in the world. And as they homed into Son Tay, a shower of tiny blazing suns released by the MC-130 flareship turned the area over the prison into day.

The HH-53 gunship raced ahead to hover over the compound, miniguns spouting flame and bringing 2 guard towers down. It throttled forward as Meadows’ HH-3 raced under the artificial light, the pilot rearing the chopper nose up, and letting it settle towards the ground. Rotors bit into tree branches shearing off wood and metal sending them twirling through the air.

The chopper slammed hard to earth. The rear deck lowered and men poured out, flame stuttering from their CAR15’s, tearing flesh and bone as tracer bullets etched a storm through the windows and open spaces of the compound. Another guard tower exploded. Meadows shouted through a bullhorn “Get your heads down we’re Americans, we’ll be in to get you in a minute.” The support force blasted a cavernous hole in the wall near prisoners’ barracks and sped through. They blew the locks on the doors and stepped in to find…nothing.

“Negative items,” blurted from radios, as firing died down. Nearly 50 guards lay dead as Meadows and Sydnor’s men withdrew out the hole. They boarded the choppers and lifted off, unaware that a navigation error placed Bull Simons group outside another camp complex where they tore into what appeared to be Chinese advisors, killing some 200 along with their Vietnamese allies. Simons ordered his chopper back and got his men out, linking back up to the force heading towards Laos.

Taking stock of the situation, the force suffered just two lightly wounded, but had recovered no prisoners. The men stayed glum and silent on the long trip back to Thailand, unaware that apart from rescue, they’d given the POWs something needed almost as much.

Morale.

Over the following days, North Vietnam rounded up its prisoners and placed them even closer to Hanoi where controlling them came easier. They removed men from solitary confinement and placed them for the first time in years with other Americans. Treatment improved, as did food. Many could bathe regularly. Word of the raid spread throughout their ranks. Whatever doubts they harbored vanished. America cared. It was that simple.

After it was all over, an inquiry was made as to why Son Tay came up empty. It turned out the prisoners were moved months before, as heavy rains created flooding that rose to within a foot or two of the compound. And it may not have been Mother Nature’s work alone. Operation Popeye, a project which involved seeding the clouds for more rain over North Vietnam in ’67 and ’68, then Laos from ’69 to ’72, was underway. So secret it was, that not even the Secretary of Defense knew about it.

Whatever the reason, Operation Kingpin remains America’s most dedicated attempt to retrieve its men captured during the war, and the effort is perhaps summed up in one word by former POW John McCain when asked to describe he and his comrades’ feelings upon hearing of the raid.

“Elation.”

COMMENTS