During the course, I started watching AMC’s “Turn,” which tells the story of the Culpepper Spy Ring that provided Washington with intelligence during the American Revolution. The series features Robert Rogers, a loyalist guerilla fighter who the 75th Ranger Regiment claims as an ancestor and father of American Ranging. The character of Roberts is obsessed with tracking, and in one instance is furious with a conventional British soldier who contaminates the scene of an ambush by the Continental Army.

Rogers began rifling off the same tenets that we had been taught during the course: Had he been given access to the scene, he could have determined access routes, the number of men, the planning of the assault, and very well could have determined that it was an American spy that betrayed the British troops. Rogers’s insistence on tracking as a critical skillset for warfighters is immortalized in his standing orders, which live on in those of the modern American Rangers.

The remaining days were spent primarily in the field, with only brief lectures in the morning about more advanced topics (backtracking, counter-IED, tactical acuity, and small-unit tactics). Each field exercise gradually built up our confidence as we moved further away from the comforts of the spoor pit and into the harsh reality of the woods. The cadre intentionally boosted our confidence as the evolutions became more complex, providing teaching points and encouragement from their years of experience. The students split into teams and headed for the woods, where we would take turns being trackers and quarry.

Though on the surface it would appear to be an elaborate and methodical game of hide-n-seek, we were rapidly building our skillset brick by brick. Each venture deeper into the woods taught us to track with greater “economy of movement,” to be silent and preserve the spoor, hone our situational awareness, and move securely as a unit without exposing the team in open terrain. On our second day in the woods, the quarry began using anti-tracker devices (emphasis on tracker– more about anti-tracking later).

Now we would need to blend tactical acuity and tracking skills so that we could pursue the quarry, but do so without walking into an ambush or an anti-personnel device. The cadre reminded us that we would need to use a “sliding scale,” constantly switching between our micro-focus on the minute details/spoor and our macro-view of our surroundings in scanning for potential threats.

“The best tactical trackers have short attention spans,” bellowed one of the cadre in a grave voice that was devoid of sarcasm. “They focus on tracks for just the right amount of time before breaking their concentration and looking up to check the greater environment around them. Then, they look back at the ground with a fresh set of eyes.” He was right.

As we patrolled along a small ridgeline in pursuit of our quarry, I glanced up to scan for possible egress points down the ridge and “track traps” (soft patches of earth that hold clear tracks) that might indicate where the quarry went. I scanned the terrain and the natural choke points. I slowly approached a deer trail between two scrubby trees, where two tracks had been preserved in a patch of fine dirt. My first glance at the narrow pass between the branches came up clean, but as I got closer, I noticed the razor-thin glare of the tripwire that had been set to snare my teammates and me.

The tripwire was nothing more than a training dummy that emitted a loud, repetitive shriek, but the lesson was clear: Tactical acuity and awareness of your surroundings is a matter of life and death in difficult terrain. We carefully brushed back the branches hiding the device before disarming it and documenting the tracks of the quarry that had placed it. Once we caught up to the quarry, we asked them to show us their boots and correctly identified the “insurgent.”

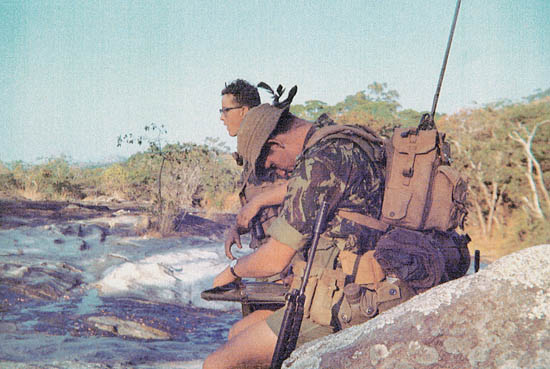

For the remainder of the course, it would be our charge to correctly and empirically identify the specific culprit for each IED placement, weapons cache, and clandestine trail marker. The final exercises covered more terrain, through mediums difficult to track in, and without any verbal communication. Security became more important as we carefully moved through open areas. Potential ambush points were glassed with optics by the flank trackers before the rest of the team moved forward.

I had always relied on convict movies like “Cool Hand Luke” for my knowledge of anti-tracking: brushing up tracks, moving through water, or using roads where no tracks could be preserved. In reality, brushing up tracks only conceals your numbers and leaves an even clearer and more defined trail for your pursuers. Moving through rivers or water allows trackers to run parallel to the river, scanning for the obvious wet tracks that you would leave while exiting the water, speeding up their chase. Several elite military units have approached TSDTS for anti-tracking training, but there is no “anti-tracking” curriculum; one must first learn to track before using methods to hinder the efforts of trackers.

By graduation, the tactical applications of tracking rang clear and true for me: “the ground doesn’t lie.” If the simple, scientific principles are applied correctly, they can be used to apprehend a fleeing insurgent or criminal, gather intelligence about their operations, or identify IEDs and other hazards to friendly forces.

From an intelligence perspective, the truth told in the spoor’s story can be used to critically evaluate an asset’s intentions or the validity of their information: For example, an asset whose tracks intentionally avoid IEDs on the way to a meeting but denies knowledge of their existence is not one to be trusted.

Despite the vast applications of tactical tracking on the modern battlefield, there is still much to be done to bring the skillset and its lessons in tactical acuity to the American warrior ethos.

Editor’s note: This article is courtesy of the Applied Memetics, LLC Blog.

COMMENTS