At Gettysburg, Battery A took position on Cemetery Ridge near a kink in the stone wall that soldiers would soon call the Angle. It was a key point in the Union line, where any serious break could ripple out into disaster. The placement meant the battery would see the elephant up close.

“I Will Stay Right Here and Fight It Out”

On July 3, the third day of Gettysburg, Robert E. Lee lined up roughly 150 Confederate guns on Seminary Ridge and opened an artillery barrage that shook the continent. Cushing’s battery sat squarely in the middle of the Union target zone on Cemetery Ridge. Confederate shells smashed into limbers, caissons, and men, killing officers and horses and tearing apart ammunition chests.

Cushing caught a fragment through the shoulder, then another round tore into his abdomen and groin, spilling his intestines. By every normal rule of war, that should have been the end of his day. Higher command ordered him to the rear. He refused and stayed with what was left of his guns, reportedly holding his belly with one hand to keep things where they belonged while directing fire with the other.

As the Confederate infantry of Pickett’s Charge closed in, the battery was down to two guns and a clutch of gunners. Cushing had those remaining rifles dragged right up to the stone wall to fire canister at almost point-blank range into the gray ranks. His voice failed, so First Sergeant Frederick Fuger physically supported him and passed his orders down the line.

Accounts from the field say his last command was to adjust the range as Virginians closed in. Moments later, a bullet hit him in the mouth and exited through the back of his skull. He died on the line he refused to abandon. Cushing was 22 years old.

Memory, Monuments, and a Long Road to the Medal

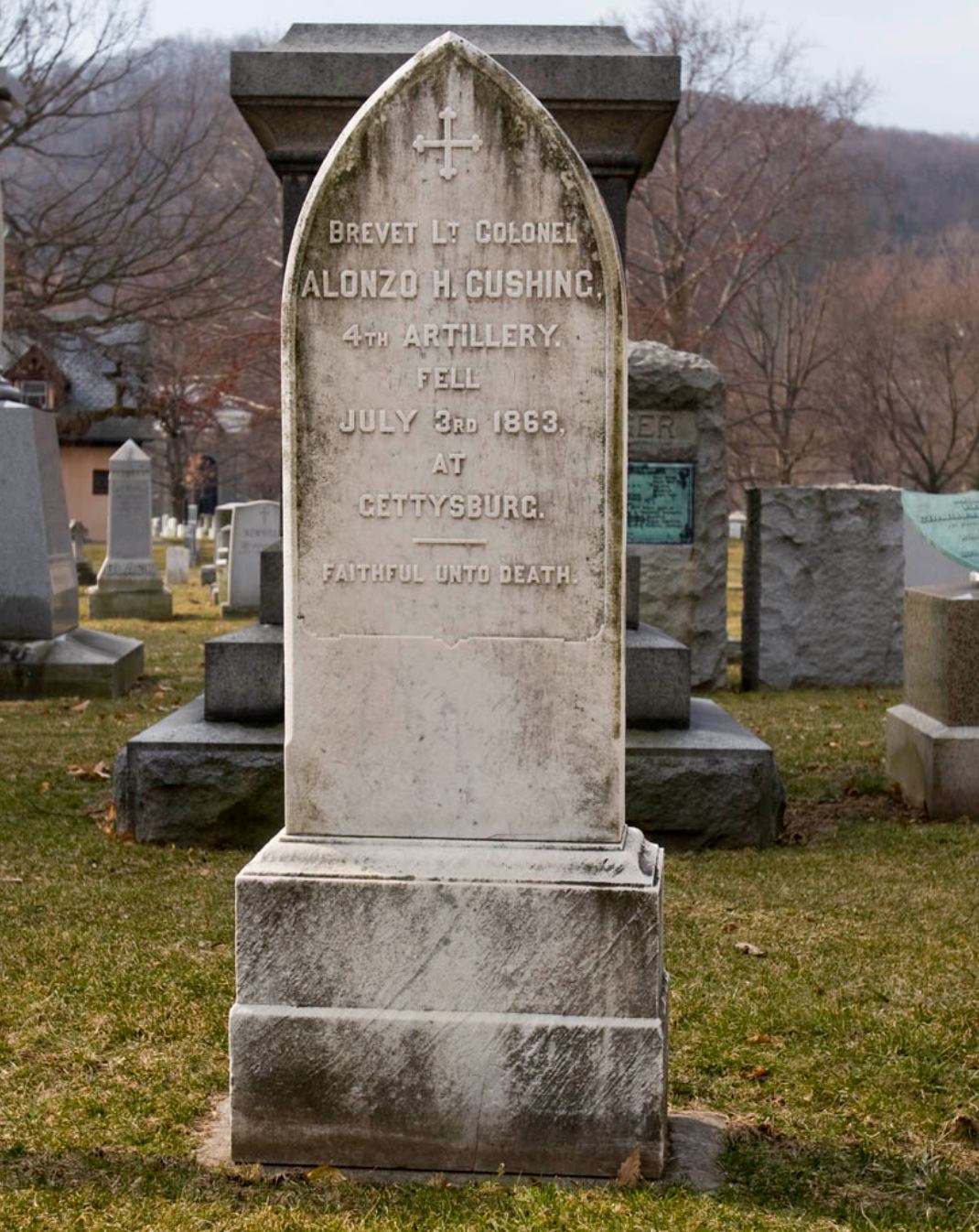

The Army buried Cushing at West Point under a stone that reads “Faithful unto death.” He received a posthumous brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel, and his name lived on in after-action reports and in the stories of men who had seen him stand by his guns in that storm. A granite monument and a marker on Cemetery Ridge mark the ground where his battery fought and where he fell.

What he did on July 3 met any standard for the Medal of Honor of his day, yet nothing came. Early on, there was a bias toward awarding enlisted men, and officers were often considered already “recognized” through promotion and brevet rank. Cushing’s courage faded into the background noise of Civil War legend.

It took a Wisconsin neighbor, Margaret Zerwekh, to drag his story into modern daylight. In the 1970s, she began lobbying to have Cushing recognized. The campaign ran for decades and required Congress to waive the usual time limits on the medal. After false starts and a failed attempt to tuck his award into a defense bill, the provision finally passed.

On November 6, 2014, President Barack Obama presented the Medal of Honor for Alonzo Cushing’s actions at Gettysburg to his distant cousin Helen Loring Ensign in a White House ceremony.

That was 151 years after Cushing died behind his guns. The official citation calls out his “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity” at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty, language that fits what his men already knew as they watched him refuse evacuation and fight a lost body through one more fire mission.

The guns on Cemetery Ridge are long silent. The stone wall is a tourist stop. Yet the image of a young officer, held upright by his sergeant, bleeding out and still calling for canister into the face of an oncoming brigade, is the kind of thing that keeps the phrase “above and beyond” from turning into a cliché.

COMMENTS