NASA’s Dawn spacecraft was launched in 2007 with a mission that didn’t garner a great deal of attention in the press. The small craft was headed for the asteroid belt, where it would be tasked with studying the development of protoplanets, or celestial bodies in orbit around our sun that could have developed into planets. By learning more about these protoplanets, we can gain a better understanding of how our own planet formed – offering a bounty of sought-after knowledge to those interested in planetary science, but not much in the way of attention grabbing headlines.

Throughout 2011 and 2012, the Dawn spacecraft maintained an orbit around the protoplanet Vesta, returning data and images to NASA for further analysis, before setting off for its next target: Ceres, a large protoplanet located somewhere in the asteroid ridden gap between Mars and Jupiter.

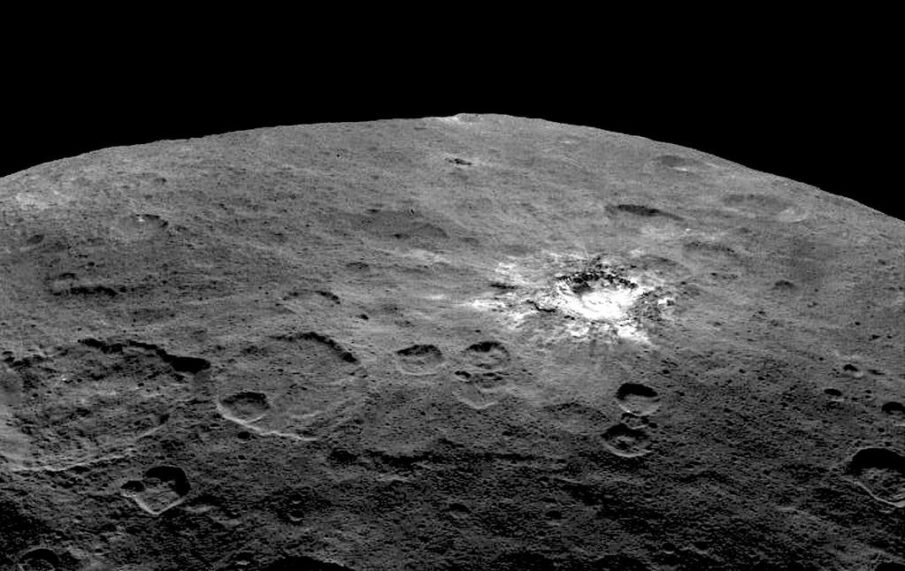

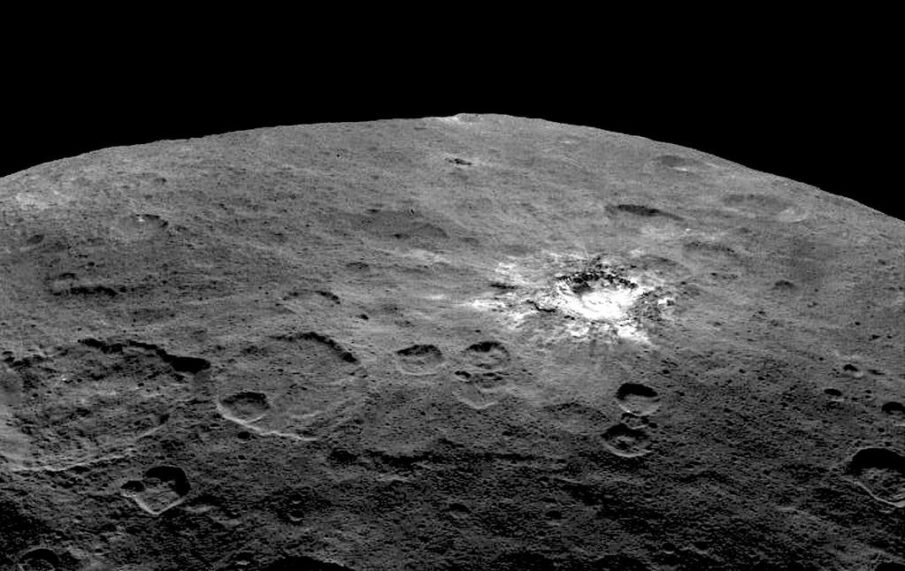

Ceres is the largest body in our solar system’s asteroid belt, with a diameter of approximately 587 miles. Over the past two years, the Dawn Spacecraft has been in orbit around the massive protoplanet, using its on board suite of analysis equipment to study the composition of the space rock and transmit its findings back to scientists on Earth – all of its work could be considered interesting in a certain regard, but wasn’t quite worthy of a press release.

That is, until last week.

On February 16th, NASA’s team of scientists studying Ceres announced that they had discovered signs of organic material on the surface of Ceres. These organic materials are a big deal – as they do not verify the existence of life on the protoplanet, but are a mandatory prerequisite for life as we know it.

“This is the first clear detection of organic molecules from orbit on a main belt body,” said Maria Cristina De Sanctis, lead author of the study, based at the National Institute of Astrophysics, in Rome.

These organic compounds, discovered by scientists using a visible and infrared mapping spectrometer on the surface, may indicate “that primitive life could have developed on Ceres,” according to Michael Küppers, a planetary scientist with the European Space Agency. Although no signs of life have yet been observed by the spacecraft, it’s important to note that this craft was not designed to conduct such an analysis, and that any life that exists in the orbiting rock would likely be microscopic and hidden deep within the rock’s interior.

“In principle life could exist on Ceres today.” Küppers continued. “It’s closer to Earth and [the] spacecraft does not suffer the high radiation levels that it experiences in the environment of the outer planets. Admittedly, in all cases it is challenging to search for life that, if it exists, is expected to be several kilometers below the surface.”

Of course, even if there isn’t life on Ceres, this discovery could have a dramatic effect on our understanding of how life developed on our own planet. If asteroids with similar compositions to Ceres impacted with the Earth billions of years ago, the organic material left behind, combined with liquid water already on the surface, could have been the recipe required to get kick start life on our planet.

Organic material of similar composition has been discovered elsewhere in our solar system, including on Mars, where scientists still believe there is the potential for bacterial life to exist deep beneath the planet’s surface, but it came as a surprise to many in the scientific community to find such compounds on what is effectively a large asteroid. It could mean that this necessary building block for life is found commonly throughout the universe, and that large asteroid-like bodies could actually harbor life if tidal or tectonic movement within the protoplanets are able to produce enough heat to melt water-ice and mix with the organic materials.

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft has reached the limit of its capabilities in the hunt for life on the surface, and is now adopting a wider orbit in order to study the celestial body from a higher altitude. NASA has already been entertaining ideas for manned missions to asteroids in our solar system, as well as unmanned missions seeking life on other planetary bodies like Jupiter’s moon Europa, but perhaps with such promising new discoveries about the potential for life within the closer asteroid belt, we may see a shift in NASA’s strategy moving forward.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

COMMENTS