‘You live dangerously, my friend.’ Schenke had only met Hauser’s wife on a handful of occasions, but that was more than enough to realize that she was formidable. ‘Even without being shot at.’

Both men were quiet for a moment as they recalled the incident at the Abwehr headquarters where Hauser had taken a bullet, then the sergeant turned to a thin man in his mid-twenties sitting at another desk. He had fine white hair over a gaunt, bespectacled face, and unlike the others, he wore no coat but sat in a simple dark suit and tie, apparently oblivious to the cold. He was reading the front page of the Völkischer Beobachternnewspaper. The headline story concerned the gallant resistance of the Finnish army as it held back the Russian invasion and defied the ill-equipped and incompetent legions of Stalin.

Even though a pact had been signed with Russia the previous August, the article was clearly sympathetic to the Finns. Russia put in its place, the headline ran. Schenke wondered how long such a treaty could endure between two nations with such diametrically opposed ideologies. It was odd, Schenke thought

that a very real war was taking place with high numbers of casualties – at least on the Russian side – while the land war Germany was involved in seemed to be little more than an occasional exchange of shots and the dropping of propaganda leaflets since the fall of Poland. Although, like many people, he still hoped for a peaceful resolution, he was beginning to fear that worse was to come.

‘Liebwitz, go and see if the man from the lab has finished examining those ration coupons that came in this morning.’

‘Yes, Sergeant.’ Liebwitz rose quickly and gave a nod before he strode out of the office.

Schenke felt a stab of guilt. Liebwitz had been sent to the Kripo section to assist with the investigation into the killings before Christmas. Recruited into the Gestapo, his stiffly formal attitude had not endeared him to his colleagues, and Schenke suspected that he had been assigned to the Kripo to get him out of the way. Now, he was waiting for official confirmation that his transfer was permanent. The wheels of bureaucracy were turning at their usual glacial pace, so for the moment, Liebwitz was still officially Gestapo, and that made him a target for Hauser, who treated him as the office dogsbody.

‘You could go easy on him,’ Schenke said.

‘He has to pay his dues, like any member of the team.’

‘He has nothing to prove. He’s done a good job.’

‘So far . . .’

Schenke could see that he was not going to shift the sergeant’s feelings towards the new man and looked round the office at the empty desks. ‘Where are the rest of the team this morning?’

‘Frieda and Rosa are interviewing a woman about a domestic assault. Persinger and Hofer are out rounding up a few of the known forgers and fences for interrogation about the fake ration coupons. One of them must know something about it.’

Schenke nodded. Persinger and Hofer were veterans of the police force. Both were big men who had a talent for getting information out of suspects, even without having to resort to violence. There was a no-nonsense demeanor about them that was usefully intimidating. Frieda Echs was in her forties, solid and efficient, with enough lived experience to handle situations sensitively. The section’s other woman, Rosa Mayer, was slim, blonde and striking, and was good at her job and at fending off attempts to flirt with her.

‘Schmidt and Baumer are down at the Alex attending a political education seminar.’

‘I’m sure that will broaden their minds,’ Schenke responded quietly as he considered the political training sessions held at the Alexanderplatz police headquarters. Schmidt and Baumer had joined the force since the Nazis had seized power and were therefore deemed more likely to be responsive to the regime’s propaganda. Hence their summons to the seminar.

Even so, Schenke had sufficient faith in their intelligence and detective training that he was confident they would privately question what they were told. Even though Hauser was a party member, the sergeant similarly had little time for some of the activities of the Nazi Party. The notion that there was an ‘Aryan way’ of conducting criminal investigations struck both men as a ridiculous waste of time.

‘I dare say we’ll be sent for political training at some point.’

Hauser shrugged. ‘No doubt. In the meantime, let’s just do the job, eh, sir?’

There was a subtle warning in the retort to remind Schenke that the occasional critical comment about the party was acceptable but not to push the issue.

—

About the Author

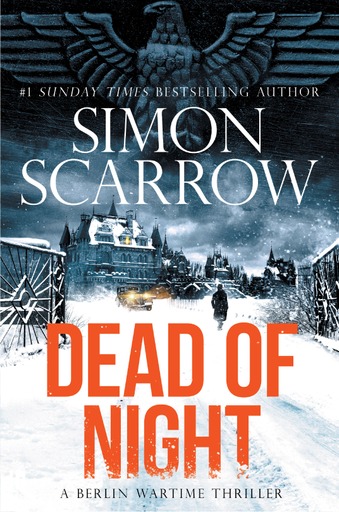

Simon Scarrow is a Sunday Times No. 1 bestselling author skilled at combining detailed research, fully realized characters, and historical accuracy. His Roman soldier heroes Cato and Macro made their debut in 2000 in Under the Eagle and have subsequently appeared in many bestsellers in the Eagles of the Empire series. He’s written novels on the lives of the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon Bonaparte; a novel about the 1565 Siege of Malta, Sword & Scimitar; Hearts of Stone, set in Greece during the Second World War; and Playing with Death, a contemporary thriller written with Lee Francis.

Pick up your copy of Dead of Night here.

COMMENTS