A power older than the country’s sidewalks

When Americans talk about sending troops into a city, they are usually talking about the Insurrection Act.

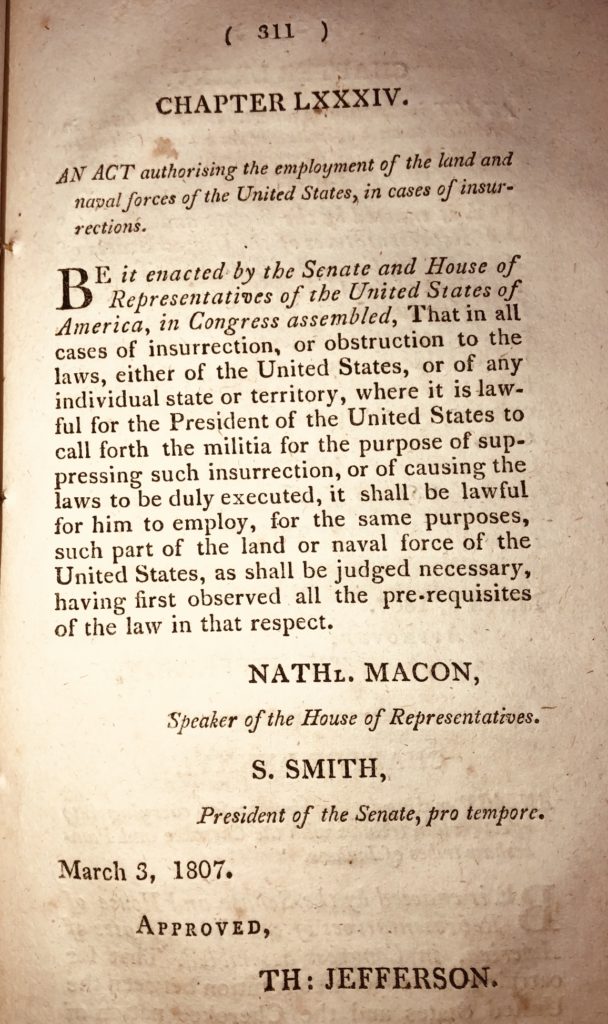

Congress first passed the Militia Acts in 1792, authorizing call-ups; the specific Insurrection Act authority was enacted in 1807. It gives the president authority to use the military at home in narrow circumstances. The modern statute lives in Title 10 of the U.S. Code, mainly sections 251 through 254. Those provisions cover when a state asks for help, when federal law cannot be enforced through the courts, and when civil rights are being denied. There is also a requirement that the president issue a proclamation telling people to disperse before troops are used.

Why Congress wrote it in the first place

The earliest version answered a simple problem from the early republic. Courts and marshals could be overwhelmed by riots or rebellion, and the Constitution gives Congress the power to call forth the militia to suppress insurrections and execute the laws. Jefferson’s era produced the 1807 act after concerns that paramilitary plots and frontier violence might outstrip local capacity.

How it evolved

Across two centuries, Congress adjusted the law but kept its core. During Reconstruction and its aftermath, federal power was used to protect civil rights when states would not. In 1871, the Ku Klux Klan Act augmented federal tools to counter organized violence, and later recodifications placed today’s Insurrection Act in Chapter 13 of Title 10. The most recent housekeeping renumbered sections and kept the proclamation rule intact. An effort in 2006 briefly expanded presidential authority for domestic deployments, but Congress rolled that back in 2008 after bipartisan criticism.

Operational Definition of “Insurrection”

The word “insurrection” as used in the Insurrection Act refers to an organized, usually violent uprising or rebellion against the authority of the United States or any state government, which obstructs the enforcement of laws or threatens governmental authority.

The Act authorizes the president to deploy military forces or federalize National Guard troops to suppress such insurrections when ordinary judicial processes are impractical for law enforcement.

Specifically, the law describes insurrection as unlawful obstructions, combinations, assemblages, or rebellion against United States authority that make enforcing laws impracticable by the normal legal course, thus requiring military intervention. Insurrection involves violent opposition to government authority, differentiating it from peaceful protests or civil disobedience.

In the U.S. legal context, insurrection includes acts that rise against the state’s authority or laws, typically with violence or intent to overthrow or seriously undermine government power. The Insurrection Act provides the statutory basis for federal military intervention in such situations to enforce laws and restore order.

Thus, “insurrection” in the Insurrection Act means a violent, organized resistance or rebellion against lawful government authority that hampers law enforcement and justifies presidential use of military force.

Where it meets the Posse Comitatus Act

Americans are understandably wary of soldiers doing police work. The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, now codified at 18 U.S.C. 1385, reflects that instinct by barring use of the US armed services to execute domestic law except where the Constitution or an act of Congress says otherwise.

The Insurrection Act is one of those express statutory exceptions. The Coast Guard is already a law enforcement service under Title 14 and is not bound by Posse Comitatus in the same way. National Guard forces under state control operate outside Posse Comitatus, but once federalized under Title 10 they are treated like active duty forces.

When has it been used

Presidents have invoked the act at flashpoints when local authority failed or federal rights were being blocked. Eisenhower used it to enforce court orders during Little Rock school integration in 1957. Kennedy used it at Ole Miss in 1962. The most recent use was in 1992, when President George H. W. Bush deployed forces in Los Angeles after the Rodney King verdict and at the request of California’s governor. Each instance turned on a breakdown of law and order or obstruction of federal authority, coupled with the proclamation requirement and a defined military mission.

What it allows, and what it does not

Under section 252, if judges and marshals cannot enforce federal law because of rebellion or widespread obstruction, the president may use militia or armed forces to restore the rule of law. Under section 253, if people are being denied constitutional rights and state officials cannot or will not protect those rights, federal forces may intervene. But the statute is not a blank check. A president must issue a proclamation to disperse, tailor the mission to the statutory trigger, and remain mindful of the Posse Comitatus line that still governs day-to-day policing. Courts and Congress watch how those lines are drawn, and recent legal analysis continues to debate how far National Guard forces can be used without invoking the act.

The modern debate

In recent years, the Insurrection Act has been discussed more than it has been used. Policy groups and legal scholars argue that the statute is broad, out of date, and should be clarified to reduce the chance of politicized deployments. Proposals include stronger reporting to Congress, clearer definitions of what counts as an obstruction of law, and guardrails on missions that look like routine policing. Whatever Congress decides, the operational truth remains the same for commanders and governors. The act is a narrow emergency tool for restoring lawful order or protecting constitutional rights when normal mechanisms fail. It is not a substitute for local policing, and it is not a domestic security strategy.

Bottom line for today’s reader

The Posse Comitatus Act sets the default that soldiers do not police Americans. The Insurrection Act is the rare safety valve when courts and sheriffs cannot do the job or when rights are being trampled. Knowing the difference matters because the distinction is what keeps the military lethal abroad and restrained at home. The law gives presidents power, but it also gives the public a checklist to measure whether that power is being used within the confines of the law.

COMMENTS