However, can you imagine the same scenario at a Russian launch control center, with absolutely rigid rules and controls, and no room whatsoever for improvisation? That’s truly a scary thought.

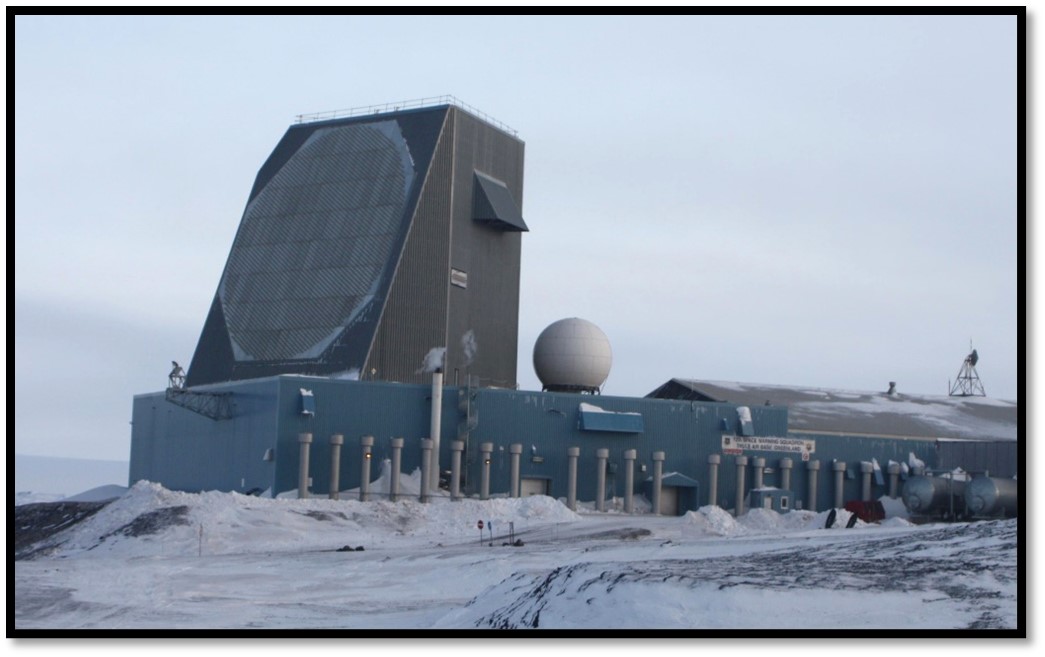

It is precisely this lingering threat of nuclear warfare, either intentional or accidental, which makes Greenland such a vitally important location. Once an ICBM launches, it has an average of just 30 minutes to reach its target on the other side of the world, so early warning time is absolutely critical. A lot of crucial decisions must be made, rapidly and accurately, in order to respond appropriately to such an enemy attack, and the U.S. administration must remain very calm and decisive in order to retaliate before enemy missiles detonate over our own soil. There is no margin for error.

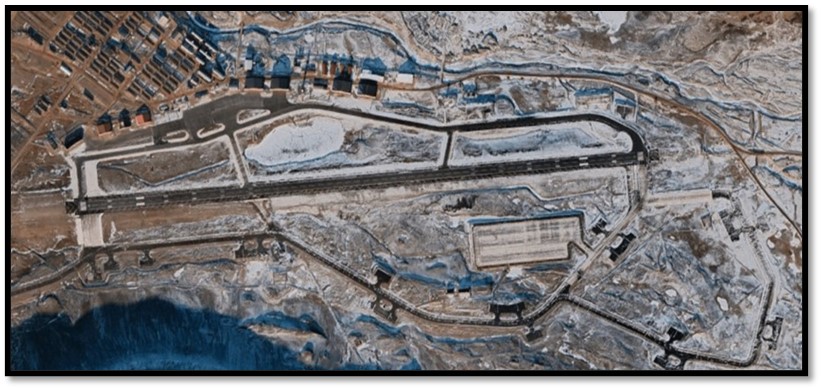

On April 11, 2025, the base commander at Pituffik, Colonel Susannah Meyers, was relieved of command by the Trump administration for “undermining” Vice President J.D. Vance after his March visit, by sending an email to all base personnel (staffed by Americans, Canadians, Danes, and Greenlanders) that included, “The concerns of the U.S. administration discussed by Vice President Vance on Friday are not reflective of Pituffik Space Base.” Ouch! Not a smart thing for a senior officer to say.

President Donald J. Trump’s comments about possibly annexing Greenland have not been popular, either in Greenland or most of Europe, with 85 percent opposition from Greenlandic citizens. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen emphasized that, “Greenland is not for sale.” Greenland’s Premier Jens-Frederik Nielsen totally agreed.

That being said, there is growing interest in Greenland from the governments of Russia, China, and the United States. There has been much discussion of Greenland being rich in rare earth minerals, but extracting them is exceptionally difficult, due to extreme weather conditions, very few roads, lack of other infrastructure (such as railroads), and the high costs of mining, so the huge nation currently has only two operating mines. The same level of difficulty applies to tapping Greenland’s oil and natural gas reserves, unfortunately.

Military concerns include the uncomfortable facts that Pituffik Space Baase is totally undefended by jet fighters or surface-to-air missiles, and therefore quite vulnerable to attack. The defense of Greenland is the full responsibility of the Kingdom of Denmark, and the Danish military contribution has been somewhat less than inspiring. Greenland does not have its own military force, and relies entirely on Danish defenses.

The Joint Arctic Command of the Royal Danish Armed Forces calls upon one or two outdated, Thetis-class patrol vessels (of a total of four, due to be replaced this year), one or two Knud Rasmussen-class patrol vessels, one Challenger 604 aircraft (also outdated) from the Royal Danish Air Force for surveillance missions, and a single C-130J-30 Super Hercules transport (of four available) for search-and-rescue, surveillance, and resupply operations in Greenland.

Since 2015, the C-130Js have been equipped with the Airdyne Aerospace (of Calgary, Alberta, Canada) SABIR (Special Airborne Installation Response) modular system, a roll-on/roll-off kit that replaces the right paratrooper door, configured with a FLIR sensor, such as the Teledyne TacFLIR 380 HLD-X, for maritime patrol duties, search-and-rescue missions, and intelligence support.

Greenland faces a number of strategic challenges, as melting ice caps open new sea routes around the island and expose raw minerals that need protection from exploitation. Also, Russian warships, bombers, and reconnaissance aircraft have been patrolling ever closer to Greenland very recently. In response, Denmark has announced plans to boost their military presence with $2 billion in new expenditures, for three new Arctic patrol boats, two long-range drones, and several new maritime patrol aircraft.

But one of the most interesting and unusual aspects of the Danish defense strategy for Greenland is the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol, founded in 1941, actually an elite, special operations unit of the Royal Danish Navy, conducting long-range reconnaissance patrolling of northeastern Greenland from a remote base at Daneborg. It consists of 12 patrolmen and two radio operators, running six dog sled teams of two men and 12 Greenland dogs, for up to four to five months at a time. A normal assignment is for 26 months in Greenland.

These Sirius operators are highly trained in Arctic survival, shooting, demolitions, reconnaissance, firefighting, engines and mechanics, first aid, sewing, truck driving, and radio communications. Their issued weapons are most unusual: The bolt-action, M1917 Enfield rifle with a 26-inch barrel in .30-06 chambering, firing a 168-grain, M2 armor-piercing round, and the Glock-20 pistol in 10mm Auto, with jacketed hollow-point ammunition loaded as every third round.

The reason for these particular weapons and ammunition is for self-defense against angry polar bears, musk oxen, or Arctic wolves. The Sirius Dog Sled Patrol uses more than 50 depot huts scattered across the patrolled area, resupplied by small boats in the southern area, and by aircraft in the northern part.

Interestingly, the Canadian Rangers, part of the Canadian Army Reserve, share very nearly the same type of mission as the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol, conducting surveillance in the far reaches of northern Canada, often with dog sled teams. While they previously carried the Lee-Enfield No. 4 rifle in .303 British caliber, since 2018, they’ve been armed with the rugged and superb Tikka (of Finland) T3x Arctic rifle (Colt Canada C19 in Canadian terminology; $3,618 U.S. dollars each) in .308 caliber, with 20-inch, stainless-steel barrel and receiver, and 10-round magazine, firing the Nosler Accubond 180-grain bullet, for self-defense in polar bear country.

This seems like a much better, more compact, and nearly a century newer rifle for the harsh, climactic conditions of northeastern Greenland. Canada is Greenland’s closest neighbor, after all, so some small amount of defense cooperation in the form of 18 to 24 new C19 rifles may be greatly appreciated.

From September 9th to 19th, 2025, Denmark sponsored the Arctic Light 2025 military exercise in Greenland, with 550 participants from Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, and Norway, to enhance operational capabilities for defending Arctic regions, and send a not-so-subtle message to the Trump administration in Washington that Greenland was still sovereign, Danish territory. This included a short, in-your-face stop by Danish F-16AM Fighting Falcon jet fighters at the American-run Pituffik Space Base.

Howard Altman concluded for The War Zone on January 28, 2025, that “Buying a few new ships, aircraft, and drones is clearly no game-changer in Denmark’s efforts to maintain control over Greenland. The announcement of the plan, however, seems to be another indication that it has no intention of giving up the island.”

Despite all the bluff and bluster, is tiny Denmark really capable of defending the massive, glacial expanse of Greenland against potential Russian aggression? Or, are American strategic, military interests the overriding factor? In any event, Greenland remains a vitally important location for the entire NATO alliance, but especially for fending off the specter of nuclear warfare through high-technology, early warning systems.

COMMENTS