Von Richthofen entered the dogfight watching over his younger cousin, Lieutenant Wolfram von Richthofen, who was flying his very first combat sortie, and Canadian Lieutenant Wilfrid May, another novice on just his third combat flight, rolled in behind Wolfram’s red-nosed triplane in his own olive-green Sopwith Camel, but both of his guns jammed, and he peeled away toward the west to return to Allied lines. Seeing this lone straggler in trouble and sensing an easy victory, Manfred von Richthofen broke away from the dogfight to follow May into a sharp, 45-degree dive over British lines, with the prevailing wind at his back, helping both aircraft to gain speed.

Canadian Captain Arthur Roy Brown, a winner of the Distinguished Service Cross, with 10 confirmed kills to his credit already, was May’s flight commander, and he immediately pursued the Red Baron in a heart-pounding, power dive in which all three aircraft reached a speed of 190 miles per hour, far exceeding their safe, design speeds.

At the beginning of the screaming dive, Brown fired one burst from approximately 800 yards, high on the left, rear quarter of von Richthofen’s Fokker Dr. I, observing some hits on the red aircraft, but the Red Baron continued to fly and fight for the next 105 seconds, so it was clearly not Roy Brown’s bullet that killed him, although Brown later received official credit for shooting him down, and his second Distinguished Service Cross.

Brown’s actual combat report for that day stated that, “At 10:35 AM…dived on a pure red triplane, which was firing on Lieutenant Wilfrid May. I got a long burst into him, and he went down vertically and was observed to crash by Lieutenant Francis Mellersh and Lieutenant May.” Except that the triplane did not go down for at least the next minute and a half, and did not crash vertically, so the report was inaccurate.

Pulling out of their dives just east of Vaux-sur-Somme, along the Somme River, at only 70 feet altitude and a full, forward speed of 120 miles per hour, May and Richthofen buzzed within a few feet of the town’s church steeple as Brown broke off to the left in a high-speed crossover, paralleling the other two aircraft from south of the river. May and the baron dropped down to a mere 50 feet altitude in the desperate chase, bobbing and weaving from side to side as Richthofen closed the distance between them to between 10 and 100 yards’ range, attempting to finish off the young, fleeing Canadian once and for all.

But, at 11:00 AM, less than a mile west of Vaux, one of his machine guns jammed and another broke a firing pin, so he suddenly found himself alone, unarmed, at least two miles behind enemy lines, and at dangerously low altitude.

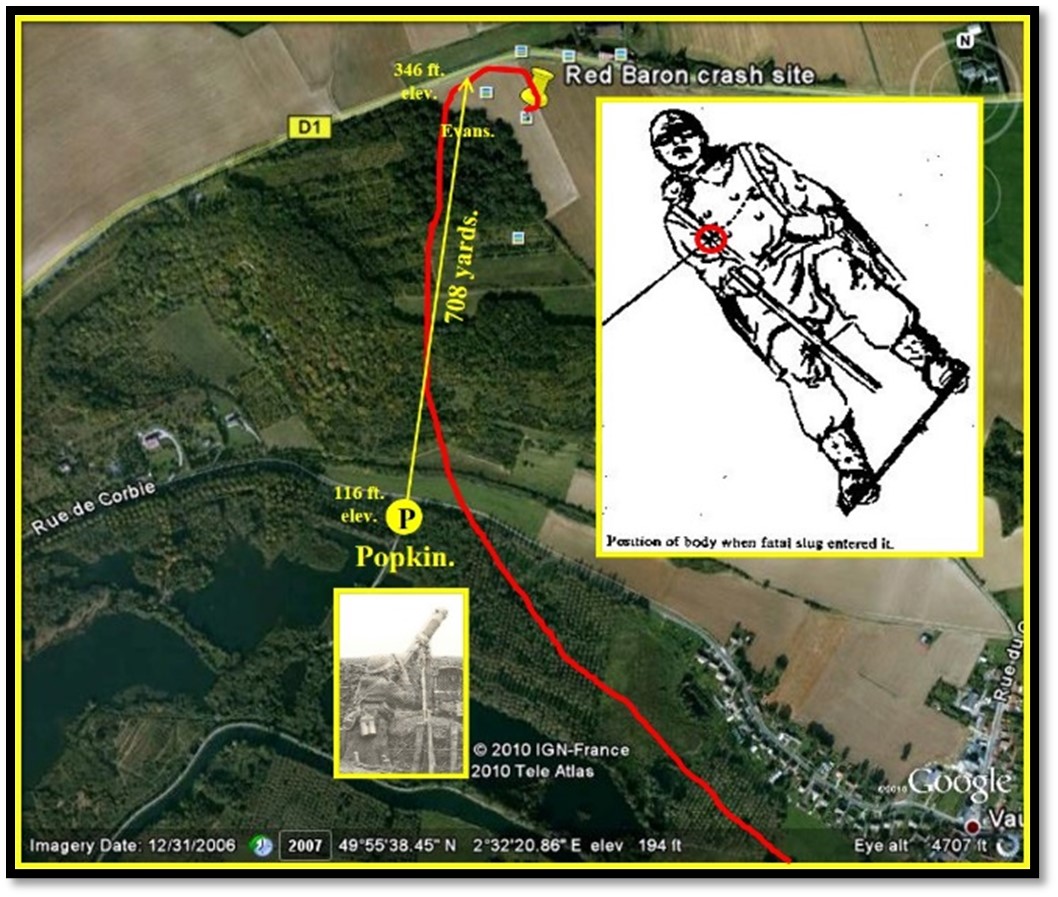

By now, May and the Red Baron had turned northward, directly toward Australian ground gunners Robert Buie and Willy John “Snowy” Evans of the 53rd Australian Field Artillery Battery, 5th Division, with Lewis machine guns, and Sergeant Cedric Bassett Popkin, age 27, of the 24th Machine Gun Company, with a Vickers gun. Popkin fired first, from a left, forward angle, with a 10-second burst of 80 rounds, hitting the front of the red triplane and startling Richthofen, who next flew directly between Buie and Evans.

They both engaged him with short, frontal bursts, scoring a few visible hits, but by this time the Red Baron knew that he was in real trouble, and over Morlancourt Ridge (346 feet elevation), just behind Buie and Evans, he executed a sharp, 80-degree, reversing turn (a classic, climbing, Immelmann Turn), with a steep, 500-yard climb to 300 feet altitude, turning abruptly east, toward the German lines.

Just as Richthofen reached 300 feet, Sergeant Popkin fired a sustained, 25-second, 200-round burst from 708 yards (precisely measured on Google Earth) to the south with his water-cooled, Vickers machine gun, at an upward angle of about 15 degrees, with the German aircraft flying approximately 530 feet higher in elevation than Popkin’s position (116 feet elevation) near the river. He later accurately reported that, “I opened fire for a second time, and observed at once my fire took effect. The machine swerved, attempted to bank and make for the ground, and immediately crashed.”

Shot directly through the heart, the Red Baron instantly took his goggles off with his left hand as his vision began to fail, and threw them to the ground below, then he cut the engine and crash-landed his aircraft, ripping off its undercarriage as the triplane came to rest in a sugar-beet field just across the Bray-Corbie Road (Route D1) from the Saint Collette brickworks. He lived just long enough to be heard to utter one word, “kaputt” (“broken/finished”) before he died.

Unfortunately, von Richthofen’s wallet, gold watch, diamond ring, 2,000 French francs (about $380), monogrammed handkerchief, identity disc, flight gloves, and the bullet that killed him all disappeared as war souvenirs of the Australian ground troops. His aircraft was likewise stripped clean, with only a few surviving parts now in museums.

According to The Red Baron’s Last Flight by Norman Hanks and Alan Bennett in 1997, “Soldier Emery came to a good pair of binoculars, and soldier Jeffery secured himself the 9mm Luger-Officer pistol,” and Sergeant Norman Symes apparently recovered a parachute and took it to headquarters. While von Richthofen was known to be an expert shot with a pistol, revolver, or hunting rifle, no other sources or historians have ever mentioned a pistol or binoculars recovered from his downed aircraft, so there is simply no supporting evidence for this claim.

The Red Baron definitely owned a pair of Zeiss binoculars, but there was no photographic, eyewitness, or written evidence that he ever carried a pistol or binoculars inside the tight confines of his aircraft cockpit, especially in the very-snug, all-aluminum, “bucket” seat, which now resides on display in the Royal Canadian Military Institute museum in Toronto, Canada, donated in 1920 by Captain Roy Brown himself. A 1918 Heinecke parachute was possible, but existing photos of von Richthofen preparing for his last flight do not show a parachute on him, although another German pilot standing nearby was wearing one.

The baron’s fatal wound was probed by doctors, who found that the bullet did not tumble, as was characteristic of a close-range, high-velocity round, but drilled cleanly through his chest from right to left, and from a low firing angle, indicative of a bullet fired from more than 600 yards away, and traveling at reduced velocity. There were five bursts of machine gun fire directed toward his aircraft by four separate shooters, but the only gunner who fired from the correct angle to make this fatal shot was Sergeant Popkin.

An original, eyewitness report by Lieutenant Donald L. Fraser, the Brigade Intelligence Officer, was sold at auction in New York City in October 2015. Fraser helped to pull von Richthofen’s body from the cockpit, and later wrote, “I am strongly of the opinion that he was first hit by Sergeant Popkin’s shooting.”

But the Royal Air Force decided that it was impossible for such a daring, dashing, heroic figure as the Red Baron to be killed by anyone other than another valiant, fighter pilot and commissioned officer, so the official credit went to Captain Roy Brown. It was simply inconceivable that a muddy, bedraggled, enlisted foot soldier, and an Australian at that, a foreigner, from Britain’s former penal colony, could possibly kill the greatest air ace of the war, despite the glaringly obvious fact that only Cedric Popkin was in the perfect position to fire the fatal shot.

Von Richthofen was buried with full military honors in Bertangles Cemetery, France, on April 22, 1918, receiving an unprecedented 36-gun salute from the Royal Australian Army. Even most presidents and monarchs are customarily afforded only a 21-gun salute, so this was extraordinarily high praise, indeed. His body was exhumed several times after the war, and moved first to Fricourt, France, then to Berlin, Germany, and finally to Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1976. The baron’s Oberursel Ur. II rotary engine and twin, Spandau machine guns now reside in the Imperial War Museum in England.

In his own autobiography, Der Rote Kampfflieger (“The Red Battle Flyer”), published in 1917, Manfred von Richthofen had prophetically written that, “Death may be right on my neck. I often think about it. Higher authority has suggested I should quit flying before it catches up with me…The only thought which I had was, ‘It is stupid, after all, to die so unnecessarily a hero’s death.’”

He also added that, “Victory would accrue to him who was calmest, who shot best, and who had the clearest brain in a moment of danger,” a statement that could certainly apply to Sergeant Cedric Bassett Popkin’s exceptional calmness and skilled shooting at that red, Fokker triplane in the morning sky.

But the Red Baron’s most memorable, self-fulfilling prophecy was, “Fly on and fight on to the last drop of blood and the last drop of fuel, to the last beat of the heart.” Thus, he grimly and accurately foretold his own destiny.

—

COMMENTS