This op-ed was written by NEWSREP guest author, Alex Benson. Part 1 can be read here.

Spending $3.2 trillion a year on a new entitlement program will not save money, even if we zero out all private spending on healthcare. The claim that spending such a massive sum amounts to savings stems from a misinterpretation of a recent Mercatus Center study, and an inane failure to understand the relevant data.

The Mercatus study does show that “Medicare for All” could save money, by way of lower administrative costs, if we go along with the outlandish assumption that providers will take on average a 40 percent reduction in payouts beginning in the first year of implementation. The one way this theoretically could happen is if Medicare became the only benefit provider—essentially, if instead of providing Americans with a public option, “Medicare for All” outlawed all private insurance and with its new monopoly had total market power to dictate to providers the terms of their reimbursement. If we do not assume automatic and immediate 40 percent provider cuts, the cost of the program increases to about $38 trillion over 10 years.

Furthermore, “Medicare for All” assumes substantial reductions in costs by way of transferring administration of healthcare expenditures to the federal government. These savings are built into the Mercatus study, even as the authors remain extremely dubious as to whether they would emerge in the real world.

Believe it or not, there are a few problems with assuming greater administrative efficiency on the part of the federal government. First, Medicare administrative costs are expressed as rates of overall costs, and Medicare per capita claims are much higher than private health insurance. If you express administrative costs as a percentage of what is being spent on benefits per capita, then, of course, they will look low relative to the more numerous and smaller payments made in the private sector. Second, the private sector has to police fraud to a greater degree than the federal government. The government does not need to worry about going bankrupt, so the requisite level of success in controlling fraudulent payments is much lower than in the private sector. When you do not need to police fraud, you do not identify it. If you do not identify it, then it fails to go into the denominator of the administrative costs-per-payment ratio, and the efficiency of the program is radically overestimated.

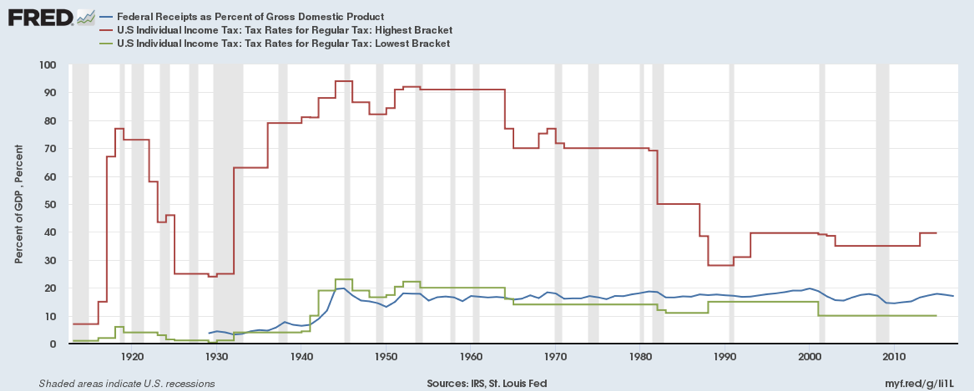

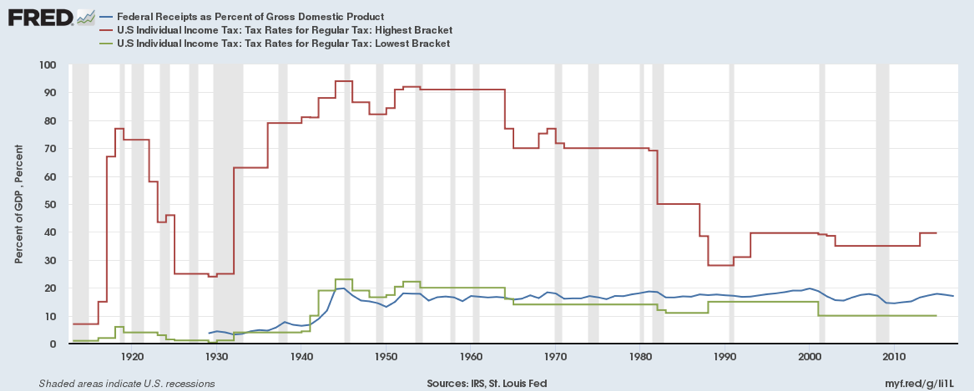

Taxing the rich cannot come close to closing the giant hole “Medicare for All” would blow in the budget. Covering the increased costs would require more than doubling federal tax revenue, and this to cover only additional healthcare spending by the federal government—Washington already spends over $1 trillion on healthcare related programs annually. Raise federal income taxes all you want, but the assumption that such massive rate hikes will bring in the necessary revenue should strain the credulity of even the most ardent social democrats. If some combination of tax increases were to bring in enough revenue such that “Medicare for All” could be fully funded, but the deficit remained unchanged, gross tax receipts would ostensibly grow to approximately 33 percent of GDP ($6.54 trillion in gross receipts as a percentage of the $19.3 trillion US GDP). Yet, tax revenues as a percentage of GDP have never risen to anything close to that. Historically, tax revenue as a percentage of GDP peaked at 20 percent twice—in 1945 and 2000. Even with the 95 percent top marginal income tax rate in the 1960s, the federal government only took in revenues of about 16 percent of GDP. In the midst of full-on central planning and massive tax increases to fight the Second World War, the federal government brought in receipts of only 20 percent of GDP. This phenomenon is known in the economics profession as “Hauser’s Law”—most economists recognize that there is a normalizing force in the economy that keeps tax revenues between 18-20% of GDP, in large part regardless of the nominal rate structure. How we are to assume that taxing the rich today will somehow overcome the very real Laffer Curve effects that have in the past revealed themselves to work on the extreme high end of rate curve is anyone’s guess.

In summary, “Medicare for All” would be extremely expensive, would increase bureaucracy and administrative expense, and cannot be funded under our current tax system. Its proponents who claim the opposite are as ignorant of the lessons of economics and past precedent as they are guilty of histrionics in their particular advocacy for this “policy of the future.” Doubling federal tax revenues, expanding the size of the federal government by leaps and bounds, and increasing entitlement liabilities by a factor of eight tend to tilt a budget toward the red. In other words, to close by again quoting O’Rourke, “If you think healthcare is expensive now, wait until you see what it costs when it’s free.”

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

COMMENTS