“Night operations are something the Afghans will be doing in a much more targeted way, the way they were trained to do but were held back under Karzai,” the official said. “We’re not going to be doing that, but there are going to be training missions with advisers along. They are not going to go onto the target with the Afghans, but they may go along in some cases and stay back.” (Rod Nordland and Taimoor Shah, The New York Times, November 23)

In December, Ghani welcomed Pakistani Army Chief General Raheel Sharif after the horror of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) attack on a school in Peshawar, Pakistan. Ghani then followed up his promises to assist Pakistani leaders in their hunt for the group responsible and ordered ANSF operations in the mountainous Kunar Province that have since resulted in over 200 militants killed. The unprecedented military cooperation between Pakistani and Afghan forces has been a high-water mark in Ghani’s first few months as president:

Some 200 local and foreign militants have been killed in a military operation in the northeastern Afghan province of Kunar where Pakistani officials believe fugitive commander of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) Mullah Fazlullah and his loyalists maintain sanctuaries, Afghanistan’s top diplomat in Pakistan said on Saturday.

“This is a proof that we believe terrorists are terrorists. There is no difference between good terrorists or bad terrorists,” Janan Mosazai, Afghanistan’s Ambassador to Pakistan, told journalists at the Afghan Consulate in Karachi on Saturday.

Mullah Fazlullah claimed responsibility for the methodical killing of over 150 people, mostly students, at the Army Public School (APS) in Peshawar on December 16. Pakistani military officials shared credible evidence with their Afghan counterparts that the handlers of the APS attackers were hiding in Afghanistan.

The Kunar operation followed visits to Kabul by senior Pakistani military officials, including army chief General Raheel Sharif, soon after the APS attack. (Rabia Ali, The Express Tribune, January 25)

Following a series of attacks, all of which occurred in volatile provinces where a resurgent Taliban threatens to permanently reverse the gains of over a decade of ISAF and ANSF efforts, Ghani stepped far outside of Karzai’s pattern and issued orders for replacement of provincial officials and security leaders responsible for maintaining stability in their assigned areas:

Ghani plans to replace officials in the northern provinces of Kunduz and Baghdis, Ghazni and Nangahar provinces in the east bordering Pakistan and Helmand in the south, presidential spokesman Nazifullah Salarzai said.

The provincial sweep will roll out over the next two to three months and will begin soon, he said.

“Senior government officials will be replaced,” Salarzai said. (Associated Press via The Guardian UK, December 1, 2014)

Earlier this month, Ghani proposed a revisiting of the previously established troop-withdrawal timeline, set for December of 2016. Making a case for a residual force that could continue to assist the ANSF as they equip and train to fight off a powerful insurgency, Ghani noted significant reluctance to remain tied to the deadline and underlined his malleable mindset with regard to the deadline. Further, he signaled support and an understanding with U.S. President Barack Obama, highlighting his willingness to work with U.S. officials to both achieve an improved Afghan security environment and accomplish the ISAF strategic objective of denying international terrorist elements an important haven:

“If both parties, or, in this case, multiple partners, have done their best to achieve the objectives and progress is very real, then there should be willingness to reexamine a deadline.” Asked by Logan whether President Obama knows this, Ghani replies, “President Obama knows me. We don’t need to tell each other.” (CBS News, January 2)

As Ghani continues to chart his own path in an effort to craft effective Afghan policy, he will have his work cut out for him. This past week, an attack at the Kabul International Airport resulted in the deaths of three American contractor personnel and the wounding of a fourth. The event reflects the effectiveness of the Taliban insurgent effort as the apparent “insider attack” serves to foment more fear between ISAF military and civilian personnel and their Afghan counterparts.

This past week, the Washington Post reported on a recent poll conducted by the Afghan Center for Socio-Economic and Opinion Research and Langer Research Associates of New York that showed an interesting and marked improvement in opinions of Afghans supporting an increased U.S. military role in Afghanistan:

In the poll, 46 percent said they would like to see a greater commitment by U.S. forces than currently in place. The United States and its NATO allies withdrew most forces last year and now have roughly 13,000 troops. The U.S. contingent is expected to fall to roughly 5,000 by the end of the year.

In recent weeks, senior Afghan officials have also indicated that they would like to see a greater U.S. presence after this year. Only 29 percent of Afghans said they preferred fewer or no U.S. forces to remain, according to the poll, which had a margin of sampling error of plus or minus 3 percentage points. Two-thirds of Afghans favored a significant role by U.S. and international forces in training Afghan forces in the future, the poll found. (Sudarsan Raghavan, The Washington Post, January 29)

Ghani’s efforts to combat the insurgency, repair a damaged relationship with Pakistan, and his willingness to engage U.S. political and military leaders on an adjustable timeline for withdrawal are good indicators of a leader possessing a malleable mind and the courage to adjust to the mission. His first few months are impressive, if only in the context of juxtaposition with the man he replaced.

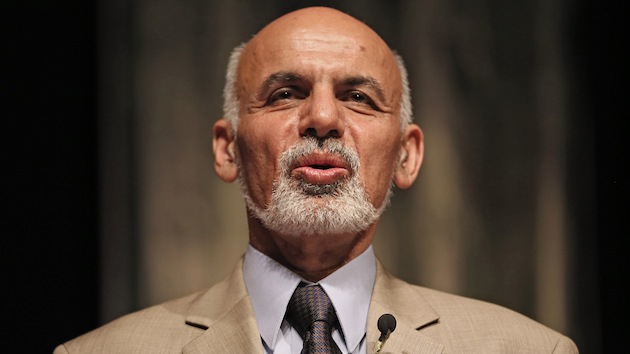

(Featured image courtesy of japantimes.co.jp)

COMMENTS