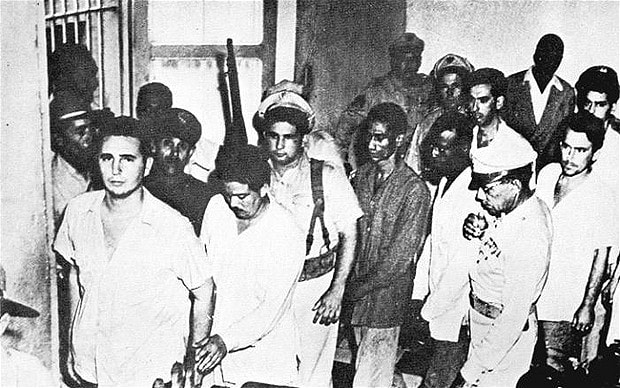

Casto’s comrades in MR-26-7 back in Cuba had started an armed insurrection in Santiago on the date that Castro was supposed to arrive, the plan being for Castro to show up with his reinforcements. However, due to boat problems and weather, the voyage took two days longer than expected, and the revolution was quashed. Now alerted to Castro’s arrival, Batista’s forces waited for them to land. On December 2, 1956, the Gramna made landfall on Playas las Coloradas. While the rebels desperately made for the dense jungle and mountains of the Sierra Maestra, they were ambushed along the way by Batista’s army. By the time they reached a safe haven, the rebel forces were down to only 19 men, including both Castro brothers and Che Guevara.

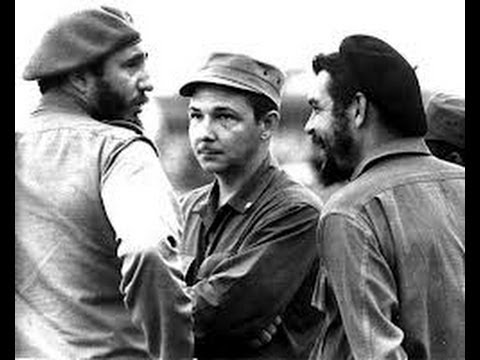

From the safety of the jungle encampment, the small band started running raids on small military outposts almost immediately, confiscating weapons and ammunition to add to their growing stockpiles. In January of 1957, the band overran the army outpost in the town of La Plata, sparing and treating the soldiers they had wounded in the fight, but executing the mayor, who was despised by the local peasantry. Castro gradually added more and more men to his cause, and by mid-1957, was able to divide his army of 200 men into three separate forces, headed by himself, brother Raul, and Guevara. Meanwhile, his faithful members of the MR-26-7 continued their guerrilla work in the more urban areas, while sending Castro and his troops needed supplies. By this time, Castro was the unchallenged leader of the MR-26-7 organization.

Desiring to band together as many other competing rebel groups to his cause as possible, Castro outwardly hid his strong beliefs in Marxism and Leninism, while his brother and Guevara were far more open about their own political beliefs. Since Cuba’s press was being censored under martial law, and with Batista claiming that Castro had been killed by government forces, Castro appealed to foreign journalists to cover his revolution. Following a famous New York Times interview by American journalist Herbert Matthews, Castro soon became an international celebrity. More interviews by American journalist followed, and Castro became a sympathetic, romantic freedom-fighting figure to many Americans.

By 1958, Castro not only controlled the Sierra Maestra mountain region, but schools, hospitals, factories, and, perhaps most importantly, an industrial printing press. Batista, on the other hand, was in trouble. Not only was his more technologically advanced military suffering defeats at the hand of the more experienced guerrilla war fighters of Castro, he was quickly falling out of favor with his American government backers. None to pleased with Batista’s censorship, torture, and executions without trials, and urged on by pro-Castro factions within the government, the United States soon stopped providing the Battista government with weapons and aid. In response, a desperate Batista launched an all-out offensive known as Operation Verano, designed to invade Castro’s mountain stronghold once and for all.

The operation was a catastrophe. The government forces vastly overestimated the number of Castro’s men, causing them to move slowly and cautiously, making them easy targets for Guevara’s experienced guerrilla fighters to ambush. Much of Batista’s force was made up of fresh recruits, little prepared for the harsh conditions of jungle fighting. They were not trained to deal with the guerrilla tactics of Castro’s amry, who would strike with tremendous firepower in well-planned ambushes, only to melt away into the jungle almost immediately. In addition, these troops were poorly paid and poorly motivated, causing many of them to switch sides and join in with Castro’s revolution. For reasons that remain somewhat murky, the commander of the operation, General Eulogio Cantillo, signed a secret cease-fire with Castro on August 8, 1958. Some speculated that the General did not want to see his military destroyed, while others suspected Castillo of having sympathies towards Castro and his revolution.

The United States looked on with despair. This, during the height of the cold war, was their worst fear: A communist taking power just 90 miles off the coast of America! Now, according to Castro, part of their cease-fire agreement was that General Cantillo would hand Batista over to the rebels to face revolutionary justice. Instead, Cantillo warned Batista that the rebels were coming to Havana. Realizing that he was finished, Batista made his dramatic resignation of the presidency on New Years eve, December 31st, 1958, telling the crowds gathered that General Cantillo was now in charge of the government. A furious Castro, assisted by the mob gathering in celebration of Batista’s ouster, then made his triumphant entrance into Havana, ordered Cantillo’s arrest, and placed himself, at last, in power.

We all know what happened next. It was the same thing that always happens whenever a dictator takes power. Believing in his own righteousness, Castro then turned his revolution into the same pattern of political thuggery that is the inevitable outcome of one man with limitless power. He jailed his opponents, used mass executions and torture to silence dissent, and caused the Cuban people untold misery for the next 6 decades. Shunned and despised by the United States, Castro sought to build ties with other socialist governments around the world, with his Russian-Cuban alliance bringing the world to the brink of nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Fleeing in mass from Cuba in whatever scrap they could cling to, generations of Cubans settled in Florida and across the United States, hoping that perhaps one day, the monster that the revolution had created would be extinguished. On November 25th, 2016, the reign of that monster, one of the 20th Century’s most towering figures, finally came to an end.

Follow me on twitter as I interview our military veterans:

https://twitter.com/BKactual/status/802927727535915008

You’d think this would be a bigger story:

An Alabama couple planted a fake bomb at an elementary school and planned to kill police officers responding to the scene in a bid to start a race war, officials said.

Zachary Edwards, 35, and Raphel Dilligard, 34, were charged with possession of a hoax destructive device, rendering false alarm and making terrorist threats, al.com reported.

The pair — who live together and are dating — confessed to calling 911 after they dropped off a faux bomb at Magnolia Elementary School in Trussville last week, but Edwards said he backed out of the second half of the plot: to shoot the cops who came to investigate.

“He wanted everybody in one place so he could kill cops. He made it clear to our guys he wanted to commit acts of violence,” Dave Hyche, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives’ assistant special agent for Alabama told the newspaper.

In his confession, Edwards claimed to be a member of the Black Panthers and the Black Mafia and talked about starting a race war, investigators said. He talked at length about his desire to kill law enforcement officials, Hyche said.

Here’s some videos of why WW1 pilots didn’t shoot their blades to pieces:

Buddy transfusions by the well-trained medic are still the answer:

BROOKE ARMY MEDICAL CENTER, Texas — Researchers, doctors and bio-technicians at the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research are working on a new, more efficient way to administer blood notice to troops in a heavy trauma situation.

One possibility? Powdered blood.

Researchers are looking at, “How do we replicate the red blood cell?” said Brig. Gen. Jeffrey Johnson, commanding general of Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, which sits adjacent to the research facility.

During Defense Secretary Ash Carter’s Nov. 16 tour of the hospital, Johnson spoke with Military.com about the latest medical technologies the institute is cultivating “because on the battlefield, that’s a big issue for us.”

It’s complicated to keep blood, “at the right temperature, in the right volume, make sure it can still store oxygen when you put it into somebody,” Johnson said. As a result, researchers are trying to develop an artificial blood product.

This is the worst stolen valor case yet:

(Brandon) Blackstone and Casey Owens did serve in the same unit in Iraq. He was apparently nearby at the time of the explosion with another platoon.

Casey’s unit had gone out to rescue a fellow soldier who had been hit by a sniper. Casey was on the passenger side of the Humvee when it ran over a double-stacked IED. The explosion threw Casey about 30 feet.

His sister says the explosion blew off one of his legs and badly mangled the other. He had burns all over his body. A piece of a carburetor hit his neck. He had hundreds of pieces of shrapnel in his body…

…Meanwhile, Blackstone left Iraq not long after Casey. He suffered a ruptured appendix and was taken to Germany for surgery, according to The Dallas Morning News.

He did not return to combat.

Over the years, Blackstone would make a business of out of claiming to be an injured warrior. He started a charity to raise money for other wounded veterans. In a video posted on YouTube, he claimed that because of a traumatic brain injury he suffered from seizures and terrible migraines.

“When I signed up, I basically felt like I had written the Marine Corps a blank check for the price of my life and I felt cast away,” he said.

He claimed that he had locked himself in his house and that he had post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I was diagnosed with insomnia,” he said. “I couldn’t sleep for long period of time…I ended up 100 percent disabled and unemployable due to my mental state and the injuries that I sustained.”

Blackstone even conned a wounded war charity into giving him a mortgage-free house in 2012.

He falsified records to receive disability checks for almost a decade. He forged witness statements from two Marines who he claimed that seen the explosion, according to federal court documents.

It all unraveled when Blackstone, an Arlington native, made the mistake of showing a picture of the mangled Humvee to one of Casey’s Marine buddies while they were attending a program that helps wounded warriors.

Here’s a YouTube video, complete with dramatic music, of this turd spinning his tail, if you can stand watching it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-c971AO8s4

This is a total sociopath. Look at him lying his off to the camera. Un freaking believable. The worst thing about this story? After repeated surgeries and ten years of living with the physical and mental pain, Casey Owens took his own life in 2014. One of the saddest stories I’ve heard yet.

You should check the credentials before penis surgery:

A South Florida woman accused of performing illegal surgical procedures that left a man’s penis disfigured accepted a plea deal and will serve time in jail.

Nery Carvajal, 49, pleaded guilty to performing medicine without a license and was sentenced to more than three years in prison Wednesday, according to NBC6.

The victim went to Carvajal for butt injections and facial treatments, then returned for a second surgery at a warehouse for a penis enlargement where she injected an unknown substance to make his penis bigger and thicker.

But the procedure went awry and instead he was horribly disfigured, the man said at the time.

Three years??? She should get the death penalty. @BKactual

COMMENTS