After leaving the Marine Corps and finishing my undergraduate degree, I took a job as a regional HR manager for a large defense contractor. At the time, I wasn’t sure why the company (which will remain nameless for the sake of this article) was willing to hire a Marine with no real human resources experience for such a role, with hundreds of employees and multiple facilities under my jurisdiction, but they offered me more money than I asked for, so I stopped asking questions and got to work ironing my suits.

Unbeknownst to me, the company was in the midst of a significant transition, and I would be the face of countless layoffs and terminations, as well as being in charge of the recruiting effort necessary to re-staff my region and help create the company’s new vision for the 21st century. My wife was working as a corporate recruiter in the tech and pharmaceutical fields at the time, so the two of us spent many a late night trolling through resumes together, tossing ones back and forth that might fit into a spot in each of our respective organizations. I hated working in human resources. Crying employees that I couldn’t throw out of my office, hurt feelings taking up bullet points in my reports to management, and driving a thousand-plus miles a week between facilities really started to take a toll…but my biggest stress wasn’t the company’s fault.

I was hired as part of a concerted effort to bring in more veterans. Our company was a DoD contractor, but the nature of our work required pretty specific qualifications that no occupational specialty in the military lent itself to in particular. Despite that, the company was yielding to pressure from its government contracts to hire more veterans, and I brought with me a sense of duty to my fellow service members that required I make every effort to help find good vets good jobs. We had the will to hire, we had the positions to fill, but the issue I ran into time and time again was actually the efforts of the veterans themselves.

Now, I’ve read a million articles about the mistakes veterans make when entering the private sector. “Don’t use military acronyms,” “don’t mention your post-traumatic stress disorder,” and “don’t act too robotic,” are common ones you can find by searching “veteran problems job hunting”—and frankly, they’re each silly. Hiring managers, like everyone else, come to the table with their own preconceived biases regarding the military. Some may love your veteran status, others may shy away from it. Some may have served and won’t be confused or befuddled by your use of crazy military sayings like “good to go,” others may not even recognize your language as uniquely military. The point is, hiring managers are people, and making broad assumptions about what will please them is a silly thing to try to do.

Instead of trying your best to pretend to be something you’re not, stop trying to passively manage the way civilian interviewers perceive you, and start actively managing your own brand. The intent should not be to find just any job, it should be to find the right job, and if you love using your Army slang around the watercooler, pretending you don’t for a five-minute meet-and-greet won’t make you fit in with an organization that would really prefer you kept your acronyms to yourself. An interview should be a two-way street, wherein the hiring manager assesses how well you’d fit in with the company, and you assess whether or not you’d want to.

Start to look at yourself as your own company. Don’t approach the interview like an unemployed vagrant with your hat in your hand, praying for a bit of charity in the form of a paycheck, act like a business that’s interested in pursuing a partnership with a new organization. What does your brand bring to the table that can benefit this organization? What does this organization offer that can benefit you? With that in mind, establishing a partnership with a new business does require that you have your ducks in a row, so in order to effectively prepare for an interview, I recommend using the tried and true Marine Corps tactic known as B.A.M.C.I.S. Traditionally, B.A.M.C.I.S. breaks down as such:

- Begin planning

- Arrange recon

- Make recon

- Complete planning

- Issue orders

- Supervise

By following each of those steps, you can produce one heck of a five-paragraph Marine Corps order, but with a slight variation on terminology and methodology, you can also land yourself a job interview.

Begin planning

Identify an industry that you’d like to pursue working in, then identify companies that exist within that industrial sphere. Once you’ve done that, you can start to look for openings you’re qualified for in each of those businesses. It can be much easier to find open positions by choosing companies first, then going to their websites to look on the “careers” section, rather than trolling through Monster or Indeed for days on end.

Arrange recon

Networking is among the most important skill sets any job-seeker can utilize, and the military offers a great opportunity to develop your network. Use social media to reach out to those you know who already work within the industry of your choice, or people you know who may have ties to that industry through official channels. Pick their brains about the field, or if possible, specific companies, and try to develop a sense of what doing that job in the private sector may actually be like.

The more people you know who have ties to the industry, the better your chances of landing the job through networking, or as a direct result of its benefits. Even if they don’t provide you with a direct contact, the background you gain will help you speak to the work intelligently once you get to the interview stage.

Make recon

Use the connections you’ve established to learn all that you can about the short list of companies you’ve decided you want to pursue. Then go to each company’s website and click on the “press” section of the page. There, you’ll find a list of press releases produced by the company. These are a great way to get a sense of any big changes the organization is currently undergoing, to find out where their new efforts are pointed, and to get a general sense of the company’s values and goals. Take notes on the important ones. A quick perusal of the press releases a company produces will often make you better informed about the organization at large than the manager who interviews you will be.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Take this opportunity to write out a few questions you could pose about the business during a potential interview. Try to come up with at least five over time, so you will always have a few that have gone unanswered throughout your conversation with a hiring manager.

Complete planning

Now that you’re equipped with a bounty of information regarding the industry of your choosing and the companies you want to work for, it’s time to take advantage of the network you’ve been developing. Ask your industry friends to reach out on your behalf, see if there are any inside tracks to positions within the organizations on your list.

Use that same information to tailor a resume specifically for the organization you’re applying to. No, don’t use that same generic crappy one you wrote as SEPS/TAPS just for the sake of completing the course and getting your DD214, actually write a resume that speaks to how you are uniquely suited to fill the roles you are applying for.

Find the job description for the position, and speak to each bullet point in that description in your resume using the same language. This is absolutely imperative, as many companies use resume-screening software to comb applications for keywords. If the job posting asks for people with experience using Oracle, and you have that experience but only cite it as “database management,” the filter will throw your resume into the digital wastebasket before any human even has a chance to put eyes on it.

Have a friend read your resume and give you feedback, but don’t make changes based on their feedback alone. Your friend may be a great copy editor, but they may not have experience hiring someone like you. Get a few different perspectives and adopt the changes that make the most sense to you, while retaining elements that you feel are important, even if your outspoken bus-driving aunt really thinks you should change them.

Issue orders (or applications)

With a resume tailored for the job at hand, submit your application and include a cover letter that you wrote specifically for the job you’re applying to. Cover letters are a chance for hiring managers to get a sense of how you communicate, and we can spot a copied-and-pasted one a mile away. Chances are we’ve already seen the same one 30 times today. Your application won’t get you a job, but if it stands out, it’ll get you an interview.

Again, be certain that the documents you submit are all proofread and free of errors. Most hiring managers won’t just throw a resume away if we spot a typo, but egregious errors tell us that you weren’t trying very hard to get this job, or your attention to detail is severely lacking, and in most jobs, either is grounds for disregarding your application.

Supervise (follow up)

This is a tough one to nail. The hiring process in many large corporations can be painfully slow, as funding gets approved, recruiters find candidates, HR folks screen said candidates, hiring managers interview them, and finally (and usually most time-consuming), some uninterested big wig will need to sign a piece of paper he or she doesn’t actually care about in order to make the offer official. All of this takes time, and if you call me every day to ask about the status of your application, I’m just going to add your number to my blocked list.

So how do you follow up without becoming a nuisance? The best way is to network within the organization you applied to so others can follow up for you. If you know someone who works in another department, reach out to them and ask if they’d be willing to mention your application to the HR manager. If you know someone in the department you applied to, ask them to make some noise about filling the vacant position. If you don’t know anyone in your new potential workplace, try calling a week after you first heard from them, and then politely ask for a timeframe within which you can expect to hear back. If the HR lady says they’ll be making a decision within the next week and you don’t get a phone call, feel free to try again once the time has elapsed.

Veterans make great employees, but never expect your veteran status to land you the job. Again, look at your service as an important part of your brand; it’s an added value that you bring to the negotiating table, but not all you bring. Many businesses are eligible for tax incentives for hiring veterans, and many others use the number of veterans they employ as an asset when negotiating contracts with the government, but that’s not reason enough to ignore a better-qualified candidate in favor of you. Approach the job hunt using the same methodologies that made you successful in uniform, because, truth be told, the corporate world isn’t terribly unlike the uniformed one: It’s just the way we think of the two that seem so different.

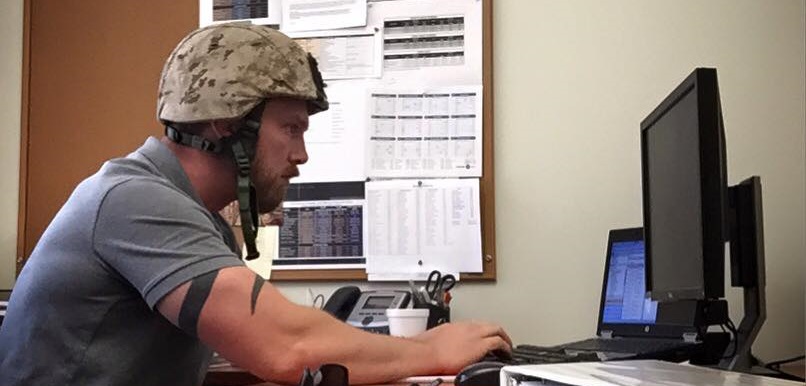

Image courtesy of AMP

COMMENTS