In the modern age of missiles we can fire at targets over the horizon, and a seemingly limitless suite of radar, infrared, and optics technologies designed specifically to keep our pilots aware of everything going on around them, one could be forgiven for forgetting that there was a time when military aviation relied almost solely on what a pilot could see with the naked eye. In the early days of aerial combat, you couldn’t hit what you couldn’t see, and combat aviation training reflected that by placing a reduced emphasis on preparing for airborne missions under cover of darkness. After all, if you couldn’t see, neither could your opponent, so nations tended to limit their dogfighting to the daylight hours.

Today, we roll our eyes at the outrageous price tags associated with each F-35 pilot’s helmet, designed specifically to ensure the pilot has total situational awareness that extends for miles in every direction. This is essential for the success of the F-35 in combat, as it lacks the speed and maneuverability of some of the jets it could face in battle—like the Russian Su-35—so it instead relies on being able to engage or avoid potential opponents before they’re even aware of its stealthy presence.

Using a big, heavy fighter that relies on awareness over speed isn’t a new idea. It can actually be traced back to World War II, when the Allies faced Nazi aerial attacks over London under cover of darkness. Londoners first attempted to counter these bombardments using spotlights and anti-aircraft guns, but soon it became apparent that, in order to win the fight for the skies, the allies would need experienced night-fliers and a plane with a high ceiling, extended loiter times, and the latest in secret tech that would allow them to spot enemy bombers—even in the dark. In response to England’s and America’s requests, Jack Northrop oversaw the development of the P-61, and the allies commenced intensive, all-volunteer, night combat training courses.

The first U.S. Night Fighter squadrons arrived in England in March of 1943, and promptly began exchanging their knowledge of night ops with the Brits, who had already mastered the art to some extent. These men were among the most heavily trained aviators the Allies had to offer, but what they were tasked with doing was something that had never been done before. Little did they know, they’d soon be faced with something no one had ever seen before, either.

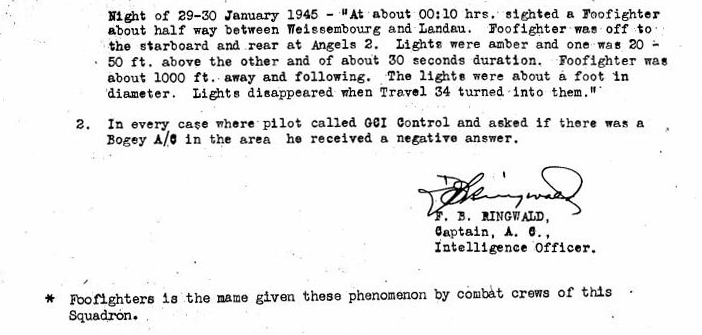

On one such night mission in November of 1944, a British flight crew comprised of pilot Edward Schlueter, radar observer Donald J. Meiers, and intelligence officer Fred Ringwald were flying along the Rhine River north of Strasbourg when they saw something in the otherwise dark sky they just couldn’t make sense of.

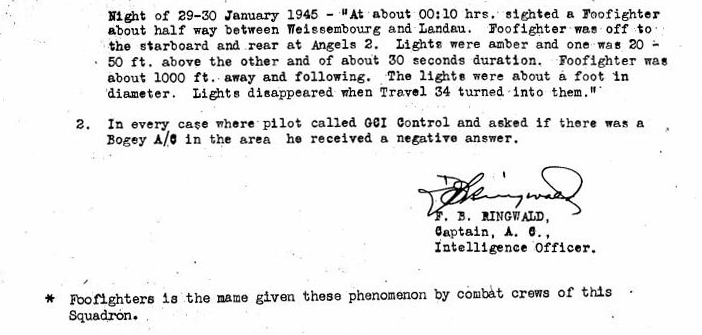

According to their report, the crew witnessed “eight to 10 bright orange lights off the left wing…flying through the air at high-speed. Schlueter turned toward the lights and they disappeared. Later, they appeared farther away. The display continued for several minutes and then disappeared.”

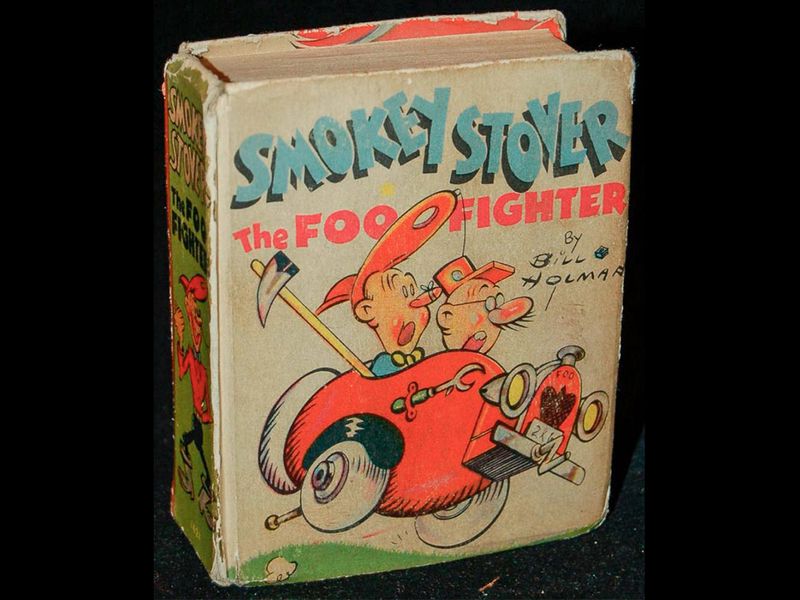

Neither the radar array on the aircraft nor radar installations on the ground registered anything in the vicinity of the strange lights, prompting the aircraft’s radar operator to name the strange lights after something he’d seen in the popular “Smokey Stover” firefighter cartoon titled “Foo Fighters.”

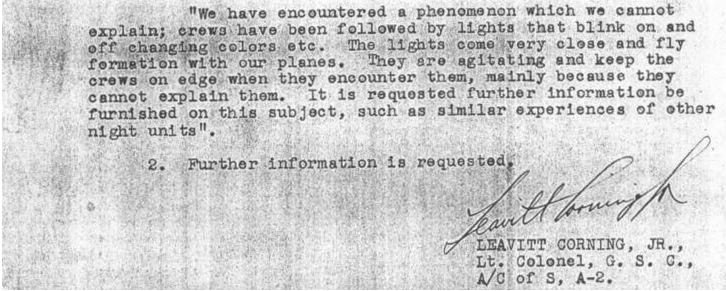

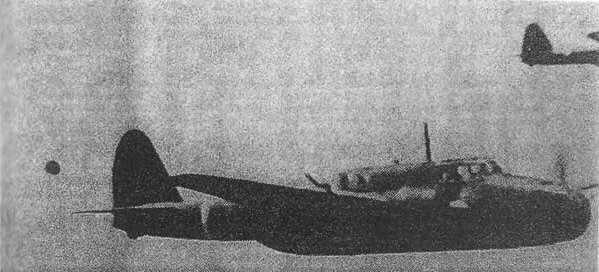

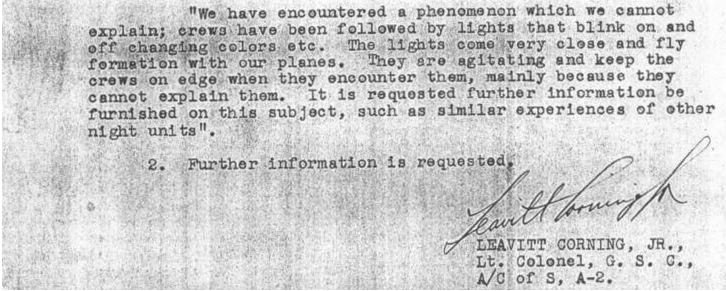

Although their report was the first, it was far from the last. Soon, crews began reporting similar lights flying alongside them at speeds in excess of 200 miles per hour. Sometimes they were red, sometimes orange, other times green. Sometimes it was a single light, but other times they would appear in formations of up to 10, often outmaneuvering the allied aircraft they seemed to shadow. Despite numerous written accounts from some the America’s and Britain’s most well-trained pilots, none of these lights ever appeared on radar.

American intelligence officials from the OSS, the precursor to the CIA, attempted to investigate and explain these sightings, but could find “no concrete evidence of enemy weapons.” Eventually, they simply filed the reports into the “crackpot” category, which was actually the term used at the time.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Richard Ziebart, who served as a historian for the 417th Night Fighter Squadron, heard about these “Foo Fighters” firsthand from the pilots in the 415th who reported them. He doesn’t think you should be so hasty to discount their reports.

“The pilots were very professional. They gave the report, talked about the lights, but didn’t speculate about them,” Ziebart recalls. He then added that, despite their professional demeanor, at least one summed up his feelings during their sighting as “scared shitless” when relaying the story to Ziebart.

By December of 1944, Robert C. Wilson, an Associated Press correspondent who spent New Year’s Eve with the 415th, had already been chasing down the story of Foo Fighters, as many involved with the Allied war effort feared these lights might be coming from some sort of advanced Nazi aircraft. His story was published in January of 1945, prompting newspapers all over America to run stories featuring flying saucers prominently on their front pages.

During the remainder of World War II and for years thereafter, experts offered any number of explanations for these strange orbs that would sometimes even appear during the day, seemingly silver or even translucent in direct sunlight. Everything from the distant lights of ships at sea to hallucinations brought about by battle fatigue were posited, but the pilots remained steadfast in their claims that the lights were real, they were airborne, and they were not like anything they’d ever seen before or since.

Today, a search for Foo Fighters on Google will likely garner quite a few more hits for Dave Grohl’s band than for UFO sightings over a war-torn Europe, but the effect of America’s first real experience with flying saucers in the mainstream media would be felt for decades. Only two years after Wilson broke the story of Foo Fighters over Europe, the now infamous Roswell incident occurred—an event in which something crashed on a farm in New Mexico, which was followed by decades of speculation about the government trying to cover up the remains of a flying saucer. For the second time in two years, American newspapers ran prominent images of alien spaceships on their front pages. Our pop culture love affair with alien invasions has been firmly planted in the world’s lexicon ever since.

So what did those British and American pilots in World War II actually see? That much is still a mystery. It seems likely that these brave men, who were the first to see heavy combat operations in a pitch-black sky, could have been fooled by the behavior of far-off and entirely normal lights due to their heightened awareness of the sky around them and the mounting fear of an enemy attack. Their reports prompted a slew of exaggerated headlines that planted the seed of such alien ships in the minds of Americans, who then embraced the idea when newspapers ran stories about more flying saucers in New Mexico a few short years later.

Of course, just because that’s a reasonable explanation doesn’t mean it’s the only one, and many continue to believe that these Foo Fighters were studying our global conflict, and that the crash near Roswell a few years later was a continuation of that research.

It seems, at least for now, there won’t be a consensus among believers and skeptics on this subject, but that’s not the most important thing to come out of this story. The mystery of the World War II Foo Fighters stands not only as a reminder that there may yet be some things we don’t understand, but of the courage and heroism demonstrated by the first Americans and Brits to take to the skies under cover of darkness, relying only on their instrumentation to engage enemy bombers and fighters.

If there were aliens in the sky, observing the ways we wage war against one another, one thing is for certain: They were watching some of our world’s bravest and most capable doing what they do best while risking their lives to keep others safe.

As far as I’m concerned, that’s a pretty good way to make contact.

Images courtesy of Air & Space, Fourth Kind

COMMENTS