Myth #2: The military industrial complex looks like Stark Industries

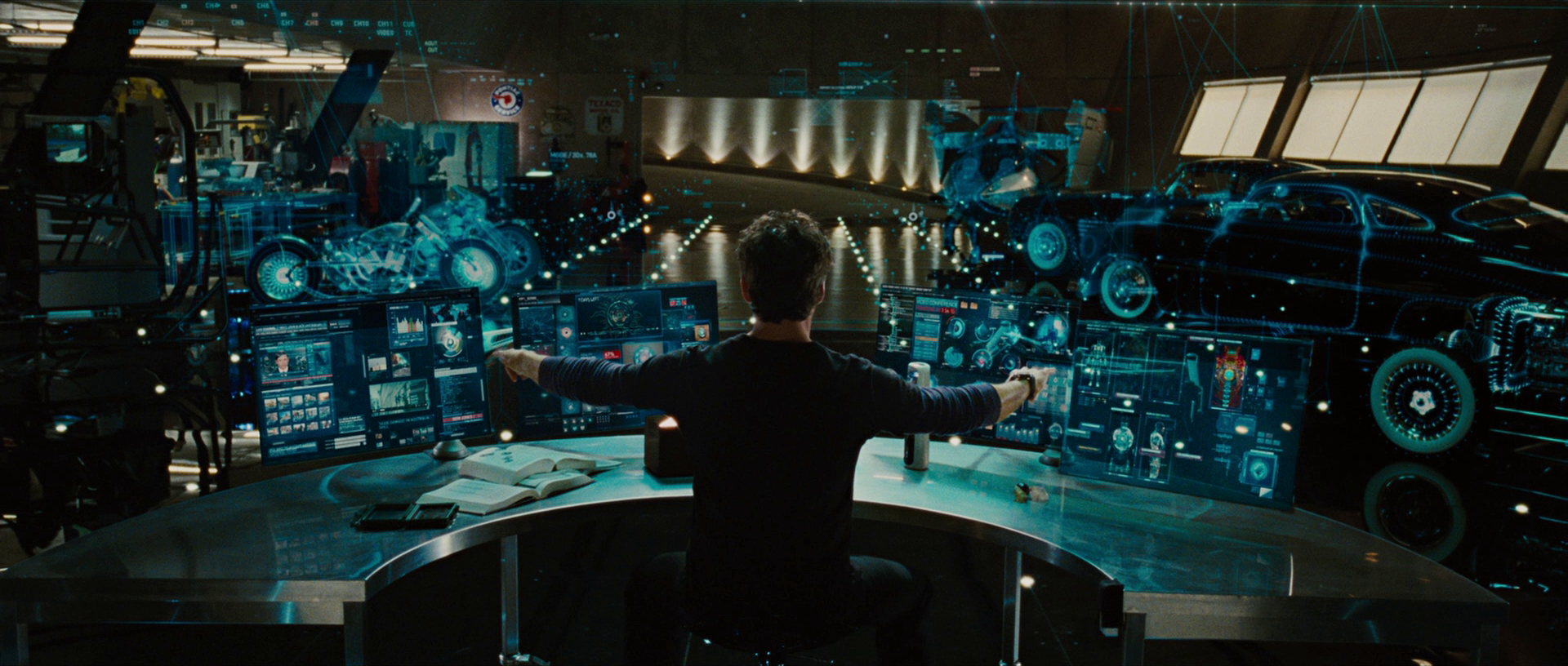

When I tell people that I worked for a defense contractor, the first thing they assume is that I was a hired gun (rather than the guy spending his afternoon trying to make pivot tables work in Excel), but when I tell them I worked in aerospace, the next thing they assume is that my factories looked like this:

Now, I’m sure that there are big-budget research and development programs that really do look like something out of a science fiction movie, but for the most part, defense contractors that work on airplanes are not pumping out the latest in top of the line hardware, they’re working overtime to produce increasingly old stuff, using increasingly old systems and methodologies, because our military aircraft are mostly old planes and choppers that we’re cobbling together to keep in the air. I recently toured a GE Aerospace facility, where after a great deal of hemming and hawing, I was allowed to go back and see how they produced the internal turbine fins that propel the Lancer B-1Bs we keep hearing about over the Korean peninsula. The Air Force only has about a hundred of those planes, but GE has to keep producing parts for them in limited runs so we can swap components out as they wear down.

And just like my facilities, GE didn’t look like they were working in a spaceship, it was just a clean factory.

I was responsible for four facilities spread throughout the Northeast; some required a security clearance just to get in the door, others were pretty relaxed environments, but all of them produced components that would eventually go into one of a number of fighter jet platforms (among other things). The employees were mostly middle-aged Asian women, because they possessed the unique combination of patience, good eyesight, and tiny hands required to solder components under a microscope – because we were still making our stuff the same way we did when the planes they went in were first built, 30 years earlier.

Myth #3: The Defense Industry really wants to weaponize animals

This one may not seem as common to you, but let’s talk science fiction for a minute. In Jurassic World, Vincent D’Onofrio spent most of the movie trying to convince Chris Pratt to help him turn their velociraptors into weaponized killing machines that could be used in places like the mountains of Afghanistan – which he argues will have to be the way of the future, as we grow more dependent on electronics (or something). The Alien franchise is also built upon the idea that the Weyland-Yutani Corporation hopes to weaponize the Xenomorphs, prompting them to send dozens of people to their slaughter and eventually even cloning Ripley just to get the baby alien out of her chest. It’s a common movie trope born out of three things: America’s general distrust toward corporations, the need for a bad guy other than the monster in monster movies, and of course, our government’s real attempts at weaponizing animals.

Here’s the thing though, those real attempts were often met with nothing but failure. We’ve tried everything from teaching cats to be spies to strapping explosives to bats, but nearly all of these programs have proven to be impractical at best. In the private sector, we were constantly worried about money. Contracts dry up, employees demand things like regular paychecks, and machines are just more reliable than monsters.

We don’t need weaponized velociraptors for the same reason we don’t currently send lions into the caves of Afghanistan instead of Marines and Soldiers. Animals usually don’t kill things unless they plan to eat them, and it costs a ton of money to develop and maintain an infrastructure around training a dangerous animal and then keeping it alive, only to lose your entire investment every 10 years or so when your genetically engineered alligator becomes too old to kick down doors.

The danger to your support staff tasked with hanging out with a murder-saurus all day would be prohibitively expensive in terms of insurance costs alone. That’s why we build missiles, bombs, drones and robots… they don’t need to be fed, they don’t bite off a trainer’s arm, and they perform with a much higher success rate than you might get out of a tiger, no matter how handsome your Chris Pratt is.

Featured image courtesy of Warner Brothers

COMMENTS