We all know the quote, “December the 7th, 1941—a date which will live in infamy….”

When U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt stood before Congress and uttered those words, there was no doubt in his voice nor uncertainty in his words. At the very moment he made his appeal to Congress to declare war on the nation of Japan, the survivors of the attack on the naval base at Pearl Harbor were still in shock at the devastation, at the loss of so many men and women, and at the realization that the invincibility and might of the United States had been tested and we had failed. But out of the attack came another emotion.

That emotion drove countless numbers of men and women to rush down to their local recruiting stations to sign on the dotted line, raise their hands, and take an oath to fight for and defend this nation from our newly sworn enemies. The attack on Pearl Harbor rallied this nation behind a common cause, and we put aside our differences (mostly) to focus our rage and our might against those who would threaten our way of life. So why have we lost sight of that determination in the face our own internal (and often petty) fights?

I am not naive. I know that we all have our opinions, our differences. This isn’t a Kumbaya piece, a plea for “why can’t we all just get along?” Nope, I know that people will never be 100 percent in agreement, and that’s cool, I respect that. This is more of me realizing the significance of December 7th and the effect that it has had on our country, even now. We have come a long way as a nation, technologically, scientifically, and socially. But events in the last 15 – 20 years have shown that we have a ways to go.

Of course, we still have those same men and women who are willing to give up their families, jobs, and at times, their limbs, their sanity, and their very lives to go off and fight this nation’s battles. Yes, some were drafted, but the majority of those who were fulfilled their duty and served. All of them, volunteer or draftee, did their duty, and in the case of so many, did so out of love for their nation, despite their feelings, their political views, their religious views, or their social views. And once the rounds started flying, they did it for the classic reason: “the man on my left and my right.”

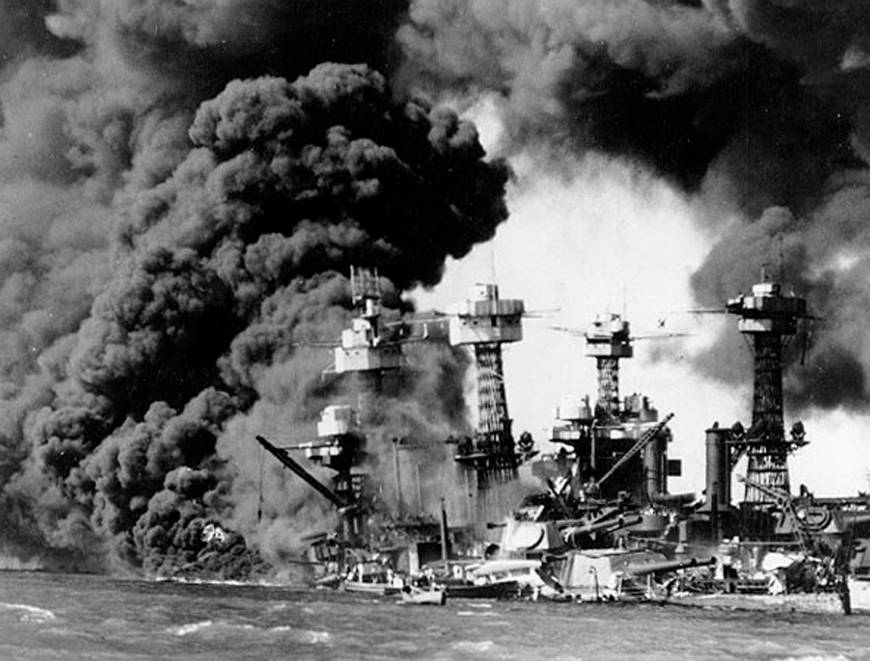

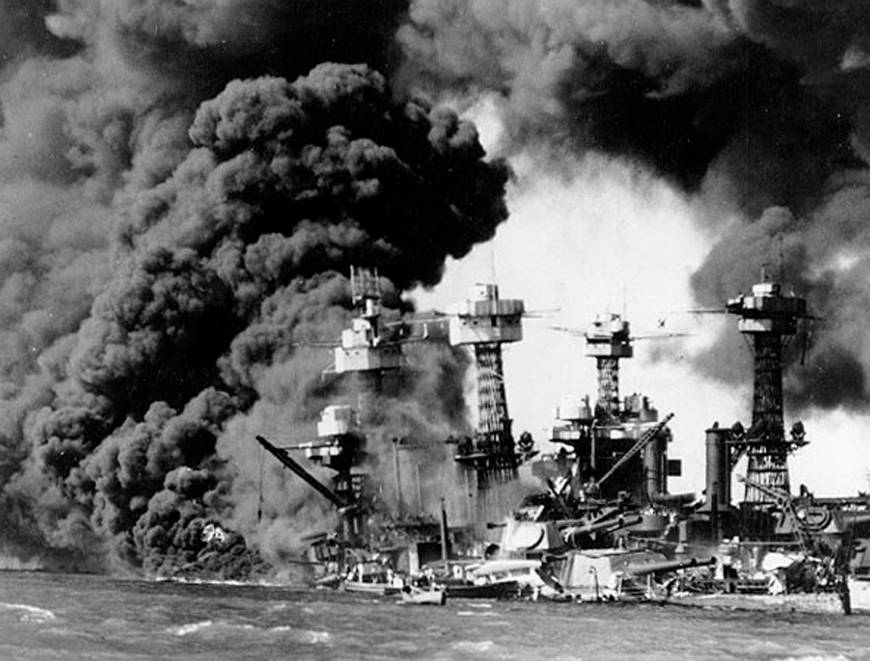

On December 7, 1941, at 7:52 a.m., the sailors, Marines, and Army Air Corps airmen were peacetime servicemen and women. They slept in, they played cards, they lounged on the beach, and some had the dreaded duty. They were from all over: Bayonne, New Jersey; Omaha, Nebraska; San Diego, California; and even Anchorage, Alaska. They were from all walks of life, from pipefitters to cooks, trust-fund babies to dirt-poor Depression-era farmers. They were also of all races. For all of them, it was the last day of a relaxing weekend, and like any good service member, they were taking full advantage of the time off. The exploding bombs from the first wave of Nakajima K5N Kate aircraft and the strafing from the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters shattered that peace and changed their worlds forever.

Yet, as shocked and bloodied as they were, they rallied. They jumped into the oil-slicked waters and braved fires to rescue their friends and shipmates. They rushed to aid stations and hospitals to donate blood and help treat the wounded. They stayed at their stations despite the shrapnel and gunfire. And they fought back. Anti-aircraft guns barked, and a few fighter aircraft that were not destroyed made it into the air, though it came too late.

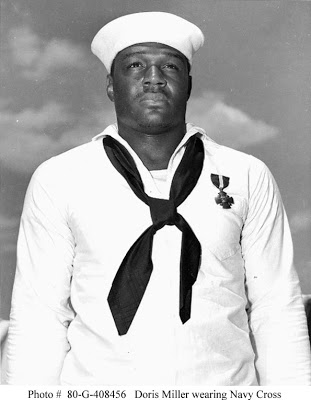

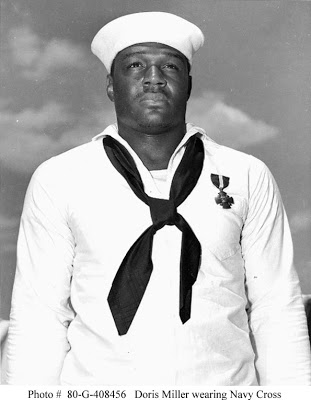

Acts of bravery were common. Messman Third Class Doris “Dorrie” Miller was the first African-American awarded the Navy Cross for his role at Pearl Harbor when, in addition to carrying wounded sailors to safety, he manned a .50-caliber machine gun and engaged Japanese aircraft until he ran out of ammunition. Captain Mervyn Sharp Bennion, commanding officer of the U.S.S. West Virginia, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for steadfastly refusing to be evacuated from his ship even though he was wounded. There was no shortage of bravery that day.

My grandfather never spoke much about his service during World War II. He would only say that he served because he loved this country. He was quick to point out when he believed we (as a nation) were wrong, but he was also just as quick to praise her when he believed that we were in the right. So it wasn’t a surprise that he chose to enlist and serve. He served in the Army and ended up in, among other places, Saipan and Okinawa. Whether he was in the thick of any fighting, I truly have no idea, but I doubt it. I say this because my grandfather served in the Quartermaster Corps and, as a corporal, ran the field PX (post exchange). He wasn’t a Medal of Honor winner, not a John Basilone or even a Dorrie Miller. And despite knowing that he was looked upon as a second-class citizen even when in uniform, he signed that dotted line anyway. He did so for his country.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

So where are we now? Do we need another Pearl Harbor to bring us back to doing our part for the nation? Like, everyone, not just those who look and think like you? 9/11 has been called this generation’s Pearl Harbor, and I agree, but the cohesion that the attacks in New York, Washington D.C., and Pennsylvania generated was short-lived, and it wasn’t long before the mud was slinging from the Capitol Hill to Facebook. We have perverted terms like “patriot,” “freedom,” and others that once meant something and were not reserved for a certain few.

Social media has provided a platform for a lot of tough talk, a lot of “turn that region into a parking lot,” and “Bring it, ISIS!” It has also given rise to (which still baffles me) cries for “safe spaces” and “X lives matter—but yours doesn’t.” We have become a nation of, “If you don’t agree with me, you are a racist/woman-hater/military-hater/not a patriot, etc.” If you don’t agree with conservatives 100 percent, you are a libtard (a freaking stupid term, by the way, along with any other -tard word). But memes and the liberal use of the caps lock key won’t stop another San Bernardino or Paris from happening. December 7, 1941 shocked the nation into the realization that we had a choice: We fight or we fold. We have been given that same choice today, but before we commit to a fight, we need to be clear on what that fight—that realistic fight—will look like, then put everything else aside, buckle down, and fight it—full bore.

Because our enemies are watching, and they are laughing.

COMMENTS