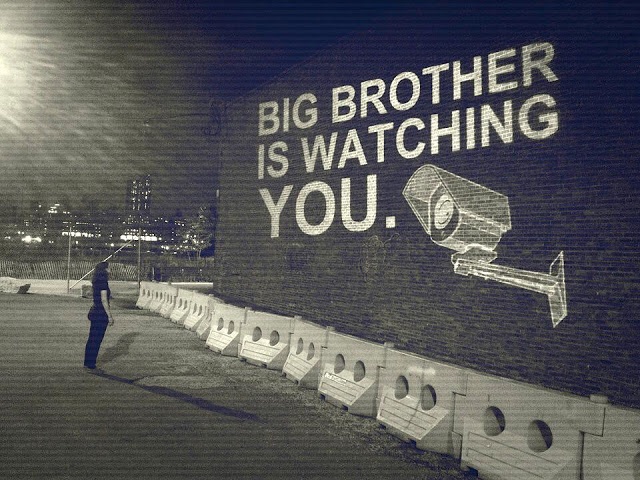

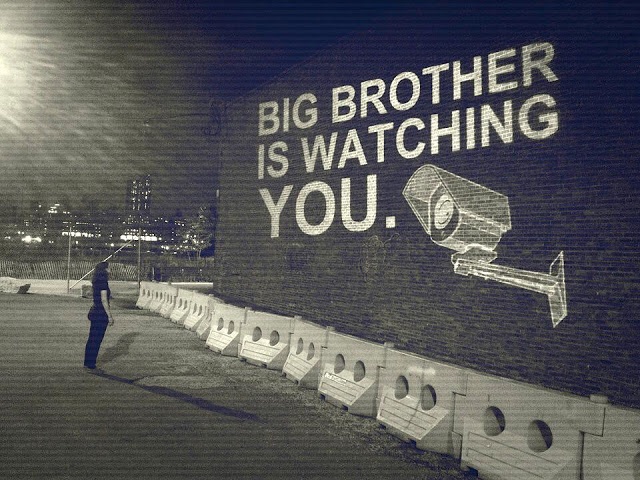

It was reported early this week that government efforts to track and monitor the coronavirus are stoking fears of global surveillance, at a time when the pandemic is in full gear and public health systems struggle to provide quality care to the increasing numbers of patients or suspected cases.

Surveillance? Now?

In an effort to track and monitor patients, individuals in quarantine, and those who come in contact with them, various governments worldwide are enacting measures to employ various surveillance technologies as a readymade solution to combat the virus’ spread. Present circumstances are challenging the age-old balancing act between individual civil liberties and privacy versus security. Even the staunchest of privacy advocates are inclined to submit that ongoing efforts to “flatten the curve” could warrant the exceptional employment of such surveillance tools.

Who’s doing what?

The Moscow Times reported last week that the use of mobile phone geolocation data would be used by authorities to track people suspected of coming in contact with anyone with the coronavirus. This announcement preceded news yesterday that Russian Czar President Putin had recently been in close physical contact with the top doctor of Moscow’s leading coronavirus hospital, who recently tested positive for the virus.

Other nations are relying on various existing surveillance tools or are developing slightly adapted methods typically used to conduct very accurate electronic surveillance. Examples of such methods are: the use of advertisement data from downloaded mobile phone applications (United States); relying on mobile phone location analytics such as 802.15 BlueTooth wireless technology to track movements (South Korea, Singapore); the use of pre-existing counter-terrorism tools such as satellite-based phone tracking (Israel); or requesting users to download a government-produced phone application (Iran).

Are you quarantined at home but need to step out for some fresh air? Not in Tawain, whose new electronic surveillance system creates and monitors an electric “fence” around the user’s quarantine location, and alerts authorities that can respond within 15 minutes of a “breach.” There are many more examples.

So what?

We can likely expect to hear more stories of quick-acting governments that pass similar legislation as they try to regain their footing by gaining critical situational awareness needed to make informed decisions during this time of crisis.

Coordinated, deliberate, and thoughtful measures designed to stem the spread of the pandemic and improve existing systems’ abilities to respond to the crisis are critical and necessary — we support these efforts wholeheartedly. Should such surveillance measures be introduced or enacted during such a time, it is reasonable to expect that such measures would be temporary and not exceed the scope or application of their original intent.

What can we do about it?

Pandemic notwithstanding, we also care about ensuring a proper, lawful, and adequate defense against unlawful governmental or non-governmental (read: criminal, non-state actor, or state-sponsored) infringement on individual users’ privacy. We’ve already observed an uptick of reporting surrounding cyberattacks conducted by opportunistic criminals looking to capitalize on the fear environment.

This has less to do with present circumstances as it does with the overall need for a sharp digital security and privacy toolkit in the 21st century. Given the rise of teleworking, remote or virtual workspaces, 5G cellular technology, the internet-of-things, and today’s information-saturated society, the onus falls increasingly on individual users to lock down their phones, computers, and online life. Organizations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Tor Project, and others are great resources to maintain awareness of “surveillance self-defense.”

We’re going to have to take it a step further.

WARNO: Stay tuned as we continue to monitor these developments and work to deliver a comprehensive guide designed to provide you with an effective, cost-effective, and holistic digital security strategy that you can implement from home, today.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

COMMENTS