On July 4, 1976, while the United States was celebrating its bicentennial, a small group of Israeli Special Operations troops was carrying out one of the most brilliant hostage rescue operations in history.

Lieutenant Colonel Yonatan “Yoni” Netanyahu — the brother of the incumbent Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — was the Commander of the elite Sayeret Matkal unit, which was tasked with conducting the hostage rescue part of the operation. The overall task force included Sayeret Matkal, as well as Air Force pilots, Israeli Paratroopers, Golani infantrymen, Medical Corps personnel, and a refueling team.

Netanyahu and Israeli commandos from the Sayeret Matkal, known to the soldiers in it as only the “Unit,” stormed the Ugandan airport at Entebbe. There, they freed more than 105 Jewish hostages and the crew of the Air France flight that had been hijacked by a combined force of terrorists. At the airport, the Israelis also had to face Ugandan troops that had gone along with the terrorists.

However, one of the stranger aspects of this operation is the fact that if one were to read 10 different accounts of the battle, the reader would come away with 10 different perspectives of how the operation went down. So, which is the correct or the most correct version of the incredible events that transpired on the first days of July 1976?

One thing that is universally agreed upon is that the raid was a brilliantly executed special operation and that only one Israeli soldier, LTC Yoni Netanyahu, was killed along with three of the hostages. Another Israeli paratrooper was paralyzed by a gunshot wound to his neck and another hostage, Dora Bloch, who was taken to a hospital prior to the Israeli raid, was murdered by Ugandan soldiers on the orders of the country’s dictator Idi Amin. But from there, all of the stories begin to differ, some slightly, others very much so.

There was a movement right after the raid, which gained ground from the press some years following the raid, to change the narrative of not only how the raid was planned but how it was conducted. One officer, Muki Betser, has been trying to say that it was he and not Yoni who planned the Unit’s operation since, during the raid’s planning phase, Netanyahu was involved in active operations in the Sinai.

With the political situation in Israel being much like it is everywhere else, some members of the media, who are very much against the current Prime Minister, took great delight in tweaking him by repeating the version that discredits the PM’s family name and legacy.

In trying to uncover what truly happened, SOFREP went to Iddo Netanyahu, the third Netanyahu brother and also a former commando. Iddo is the author of Sayeret Matkal at Entebbe the best after-action review done by anyone, including the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

On July 4, 1976, while the United States was celebrating its bicentennial, a small group of Israeli Special Operations troops was carrying out one of the most brilliant hostage rescue operations in history.

Lieutenant Colonel Yonatan “Yoni” Netanyahu — the brother of the incumbent Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — was the Commander of the elite Sayeret Matkal unit, which was tasked with conducting the hostage rescue part of the operation. The overall task force included Sayeret Matkal, as well as Air Force pilots, Israeli Paratroopers, Golani infantrymen, Medical Corps personnel, and a refueling team.

Netanyahu and Israeli commandos from the Sayeret Matkal, known to the soldiers in it as only the “Unit,” stormed the Ugandan airport at Entebbe. There, they freed more than 105 Jewish hostages and the crew of the Air France flight that had been hijacked by a combined force of terrorists. At the airport, the Israelis also had to face Ugandan troops that had gone along with the terrorists.

However, one of the stranger aspects of this operation is the fact that if one were to read 10 different accounts of the battle, the reader would come away with 10 different perspectives of how the operation went down. So, which is the correct or the most correct version of the incredible events that transpired on the first days of July 1976?

One thing that is universally agreed upon is that the raid was a brilliantly executed special operation and that only one Israeli soldier, LTC Yoni Netanyahu, was killed along with three of the hostages. Another Israeli paratrooper was paralyzed by a gunshot wound to his neck and another hostage, Dora Bloch, who was taken to a hospital prior to the Israeli raid, was murdered by Ugandan soldiers on the orders of the country’s dictator Idi Amin. But from there, all of the stories begin to differ, some slightly, others very much so.

There was a movement right after the raid, which gained ground from the press some years following the raid, to change the narrative of not only how the raid was planned but how it was conducted. One officer, Muki Betser, has been trying to say that it was he and not Yoni who planned the Unit’s operation since, during the raid’s planning phase, Netanyahu was involved in active operations in the Sinai.

With the political situation in Israel being much like it is everywhere else, some members of the media, who are very much against the current Prime Minister, took great delight in tweaking him by repeating the version that discredits the PM’s family name and legacy.

In trying to uncover what truly happened, SOFREP went to Iddo Netanyahu, the third Netanyahu brother and also a former commando. Iddo is the author of Sayeret Matkal at Entebbe the best after-action review done by anyone, including the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

Iddo realized after the fact that the IDF did not conduct a thorough analysis of the raid, including within the Unit due to its commander’s death. The IDF’s military history division spoke with Muki Betser, Yoni’s second in command for the operation, shortly after the raid but ended the after-action review of the Unit’s part in the raid there.

In writing Sayeret Matkal at Entebbe, Iddo had access to speak with the commandos involved. They opened up to him because both he and his brother, Benjamin, were also members of the Unit. While many may scoff at what would be perceived as family bias on his part, Iddo’s history is supported by the Israeli news site YNet in a four-piece article by Dr. Ronen Bergman. Iddo’s reconstruction of the events also aligns with “Operation Yonatan in First Person” a compilation of the memoirs of the Unit’s men, published in Hebrew 40 years after the raid.

Dr. Ronen Bergman, who is considered to be the lead reporter in Israel on things to do with Mossad and Special Operations, had this to say about the book by Iddo Netanyahu:

“It turns out that the version of events presented by a great majority of Sayeret Matkal’s soldiers and officers almost completely matches (apart from minor differences) Iddo Netanyahu’s version.”

One chapter in the book was written by Alex Davidi, who was a member of Muki Betser’s team that stormed the hostage hall. Davidi wrote the following passage. Davidi’s comments are a testament to the adage that a successful operation has 1,000 fathers and an unsuccessful one is an orphan:

“Muki Betser is the man who started from the time the mission ended and from then on for 40 years to make history fit his personal narrative which puts him at the crux of the operation and its success, ignoring simple facts that are perfectly clear to the great majority of the Unit’s men who took part in the raid.” (p. 192)

“Various ‘step-fathers’ took credit for the ideas, the plans, and the actual handling of the operation’s execution on the ground. But for me and my friends who took part in the raid, it was clear who the real biological father is: Yonatan Netanyahu… His fingerprints and footprints were evident at every stage that we were witness to, from the beginning all the way to the end of the operation, which to our great sorrow was also the end of Yoni himself.” (p. 192)

“With time, battles began for the credit on the planning and command of the operation in order to gain [sic] world renown. The great majority of us men did not take part in these battles. Among ourselves, we knew the truth, who did what, when, and how. The field was left open to that person who chose to take for himself the glory. When you tell a lie enough times, it takes root… We, the combat fighters, know who really did what at Entebbe.” (p. 195-196)

SOFREP had the pleasure to sit down and talk at length with Netanyahu, who was not only generous with his time but patient in answering so many questions — some of which he no doubt has been asked numerous times.

None of it would have been possible without the assistance of our close friend Lela Gilbert, who not only is friends with Iddo Netanyahu and his wife Daphne but is an accomplished author and journalist herself covering religious matters in the Middle East. She introduced us to Iddo and we were able to get insight into Yoni, the commander, as well as the person. We also leaned heavily on Iddo’s earlier book, Yoni’s Last Battle, which was initially published in Hebrew but was later translated into English. Unless otherwise noted, all of the quotes contained herein were either directly from his book or from our conversation.

“The book was based on interviews that I conducted with more than 50 of the people that were involved in the raid,” Netanyahu said. “Some of them I spoke to extensively.”

Netanyahu said he wrote the book and did the research for a very simple reason: “There was no real documentation done by the military on the raid, and I was after the facts… I believe that my book is the only faithful account [of] the Unit’s part in the raid. This is unfortunate, to say the least.”

But before the background of the raid is examined, we will look at its commander: Yonatan “Yoni” Netanyahu was a fascinating character at the center of it all. Netanyahu was a brilliant, detail-oriented, if somewhat reluctant, warrior — although “reluctant” may be a bit of a misnomer. He was in fact an outstanding soldier and leader, one of the best that Israel has ever produced.

Despite his obvious talents and the fact that he worked his way up to become the Commander of “the Unit,” he, no doubt, would have loved to have been something else in life. But events that were unfolding in his country, events that he had no control over, would constantly force him back into uniform.

Former Chief of Staff, Rafael Eitan, who got to know Yoni in 1973 during the Battle of the Golan Heights in the Yom Kippur War put him above everyone in his own peer group.

“If you compare him to other officers his age who were battalion commanders of the paratroops back then and are generals today, he was head and shoulders above them. They are great officers but he was on an entirely different level.”

One thing he wasn’t was an army politician. Yoni hated that some officers would spend too much time trying to hob-nob with the senior brass. He saw several officers run PR campaigns to further their own careers and it pained him to see that even in the Unit.

Additionally, Yoni held the Sayeret Matkal operators in very high regard. Not surprisingly, their traits are very similar to what we look for in Special Operations troops here in the United States. Yoni’s own words sound quite familiar when writing about the Unit:

“The Israeli Army concentrates within it, a type of person who is to my taste,” he wrote. “People with initiative and drive, willing to break with convention when necessary, people who do not stick to one solution, but are constantly seeking new ways and new answers.”

One of the Unit’s staff officers remembers Yoni as quite different from other commanders that he’d seen. “To a great degree, he was an intellectual… quite a bit more mature than we,” he said. “There were quite a few things we couldn’t understand then that I see differently today.”

Not long before his death, Yoni and his girlfriend, Bruria, went to Masada and climbed down the huge cistern that was on the side of the mountain. During the Jewish revolt against the Roman X Legion, the cistern kept the Jews with enough water to withstand the months-long siege.

As they reached the bottom of the cistern, Yoni read the words of Elezar Ben-Yair, the leader of the Jewish fighters. After holding out for months on the steep mountain fortress, the Romans had built an enormous ramp that their siege towers could finally knock down the walls of Masada with. On the night before the final assault, the Jews decided to commit suicide rather than live as slaves under Rome. Those words from 2,000 years ago resonated with Yoni:

“For death we were born, and for death did we give birth to our children. From death escape not even the most contented of men. But a life of disgrace and slavery… these evils were not to be decreed to be the fate of men from birth… Surely, we will die before we become slaves of those who despise us and free men we will remain as we leave the land of the living.”

Background – Air France Flight Is Hijacked

On Sunday, June 27, Air France’s Flight 139 left Israel’s Ben Gurion Airport, made a stop in Athens, and then took off towards its final destination in Paris, with 248 passengers on board. At around 12:35 pm, four terrorists — two German from the Baader-Meinhof group and two Palestinian — hijacked the plane.

The hijackers forced the plane to land briefly in Libya, before flying down to Entebbe, Uganda where at least three more terrorists joined them. The hostages were led into the old terminal building where they were guarded by terrorists and Ugandan soldiers. At the time, Uganda was run by the dictator Idi Amin.”We didn’t know at the time that Amin and his army were fully cooperating with the terrorists,” Iddo said. There the Jews and Israelis were separated from the other passengers.

The terrorists demanded the release of more than 50 terrorists imprisoned across a few countries; the great majority of them were held in Israel.

Israel was shocked by the proceedings. Despite many of the elite units believing that the country would act, because of the vast distance involved, the chances of the IDF actually conducting a rescue operation seemed far-fetched.

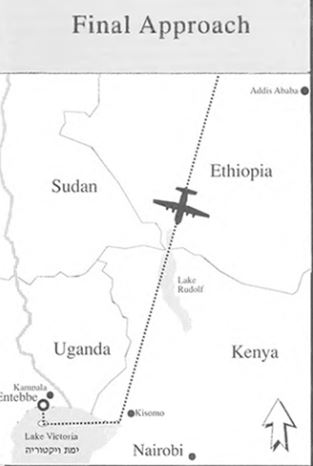

As Netanyahu and the Unit were preparing for a classified operation in the Sinai, they received word of the hijacking. Avi Weiss, the Unit’s Intelligence Officer, said that the members of the Unit that were not traveling to the Sinai were on alert waiting for the word. But once they learned the plane had gone to Entebbe, they were told to stand down because of the distance (4,000 km). The chances of being ordered to go seemed extremely remote.

But there were scenarios — calling them plans at that early stage would be incorrect — being discussed, none of them appeared viable. As Yoni Netanyahu, Weiss, and a team from the Unit were in the Sinai on Wednesday night, between June 30 and July 1, they were kept abreast of the developments by Betzer and other officers of the IDF. Betzer had been assigned by Yoni to be the Unit’s representative in the group that was looking at options. Senior leaders, including PM Yitzhak Rabin, in both the government and the IDF, also discussed possible plans of action.

On the 29th, the non-Jewish hostages were released from Entebbe in two batches: women and children on Wednesday the 30th, and the men on the morning of July 1st. But the Air France crew refused to leave their Jewish and Israeli passengers. This set in motion the planning and operation that would then be known as Operation Thunderbolt.

This was a critical time because, until the hostages were released, there was virtually no information on how many terrorists and Ugandan soldiers there were and where exactly the hostages were being kept. Thus, there was no way to plan a raid. On Thursday noon, the Israeli government — with the failed IDF operation at Ma’alot still a fresh sore, the fact that no viable plan of operations had been devised, and that the terrorists’ ultimatum, then set for Thursday, was about to expire — was thinking of negotiating with the terrorists and meeting their demands. That was always against the stated policy of Israel, i.e. that it would never give in to terrorists’ demands.

The released hostages were flown to Paris, and an Israeli officer interviewed a few of them on the evening and night of July 1-2. The released hostages described where the Israeli hostages were located, how many terrorists there were, the floor plan of the building, and other important details.

A Mossad agent flew a light aircraft over Entebbe and pretended to have engine trouble. He took photographs of the area and reported that only dozens — not hundreds — of Ugandan soldiers were guarding the building. That fact was corroborated by the released hostages. That convinced the Israeli government that the mission had at least a modest chance of success.

Obviously, timing and the speed of the operation were of the highest importance. Now, armed with some usable information, Yoni freshly back from the Sinai, got to work. They had to have a detailed plan and launch in slightly more than two days. The IDF picked Saturday night as the go-time for the raid since the terrorists’ ultimatum was for Sunday.

Yoni began his planning on Thursday evening after receiving “orders” for an operation from Dan Shomron at 8 p.m. The planning sequence was so condensed that performing it was an amazing display of soldiering by the commander: They had to plan all phases of the operation, work out all of the details, including loading and unloading of the aircraft that would participate in the operation, conduct rehearsals, equipment checks, and tie up any loose ends on Friday. On Saturday morning, a briefing with Yoni and his officers would take place. They would then depart from Lod Airport late in the morning, flying to Sinai at around noon, and then wait there for the long nine-hour flight to Entebbe.

Speaking about Yoni and the unit in general, Iddo said, “it was a tremendous example [of] the power of will… he knows, ‘I got to do this and we’re going to do it no matter what.'”

Yoni’s plan was being crafted as information from the released hostages was flowing in. It was a very fluid situation. Even during the rehearsals, as issues would pop up or more information would become available to the unit, Yoni would adjust the plan on the fly.

The plan called for five small assault teams to take down the two halls of the old terminal where the hostages were thought to be held. Betser would be in charge of those teams.

Yiftah Reicher, the Unit’s second in command, would command the two teams that would clear the west wing and the second floor, which was where the Ugandan soldiers were known to be encamped at night, as well as the Customs Area. Danny Arditi would be in command of the team taking down the east end where the terrorists’ living quarters were located. Amnon Peled would lead the team that was assigned the most important role of all: to be the first to enter the second entrance — the main one — of the “large” hostage hall where the Unit estimated that most, if not all, of the hostages were being kept. Yoni would be with the command element “next to” the two teams entering the second exit of the large hall.

But still, whether the mission would even take place was foremost on everyone’s mind. Iddo, during our interview, said that “every one of the people I interviewed for the book told me that they never believed that the mission would ever be approved or take place.”

Yoni was well aware of this. He instilled in the men the belief that the operation would take place, irrespectively of what he might have thought.

Everything changed after the Friday night rehearsal when the IDF’s Chief of Staff told the unit that he was going to recommend to the government that they be given the go-ahead.

Shimon Peres, then the Defense Minister, called Yoni in for a meeting before Friday night’s rehearsal. Peres, Iddo said, “wanted to hear straight from Yoni, with no distractions from the Chief of Staff or anyone else, ‘Can this thing be done?'” and Netanyahu convinced him that not only could it be done, but accomplished with little cost to the hostages. Yoni wasn’t so sure about the cost to his men.

“A hostage rescue mission is quite different from any other operation,” Iddo said. “Normally, if there are enemy soldiers in a building, you throw grenades into the room, to kill as many of the enemy as you can, before storming inside… but in a hostage rescue, the situation is different. Not only [you cannot] do that, once you are inside you have to find out who is an enemy and who isn’t before you fire even a single bullet. Thus, you expose yourself entirely to fire by the terrorists who are inside.”

“Those split seconds to make the distinction between terrorists and hostages takes tremendous courage,” he said. “And it has to be conducted perfectly.” However, Yoni’s confidence was unwavering and Peres was now onboard.

The Israeli plan was for the force to fly to Sharm al-Sheikh, Israel’s southernmost airfield at the time, refuel, and then fly south to Uganda to land four C-130 Hercules aircraft with 33 members of Sayeret Matkal on the tarmac of the Entebbe airport. A Boeing 707 would serve as the airborne headquarters of the mission and take off several hours after the Unit did.

The plan was for the first C-130 to land blacked out if the lights of the runway were turned off. The pilot was going to declare that he flying was in a civilian aircraft having mechanical issues and ask the tower to turn on the runway lights. Either way, they were going to land the Hercules on the runway.

The lead pilot, Shiki Shani, was thoroughly impressed with Yoni Netanyahu. “We were the same rank, yet I had respect for him that was reserved for someone with a much higher rank. [He] had a combination of an extraordinary fighter and an intellectual. I definitely had the image of someone out of the ordinary. He seemed like a hero out of our ancient past.”

After a briefing, Shani turned to his navigator and gestured towards Yoni, “That man is the greatest warrior Israel has ever had.”

On the first C-130, they would have a limo disguised as Idi Amin’s — with the Israelis dressed as Ugandan soldiers — along with jeeps filled with commandos. The Mercedes was a junker; it had a myriad of problems. During the Friday night rehearsal, the Mercedes wouldn’t start, and a jeep driver had to bump the Mercedes to get it started.

Once they would get close enough they would storm the terminal and kill the terrorists guarding the hostages. The rest would eliminate any remaining terrorists and soldiers. The paratroopers were to secure the new terminal.

The unit would then gather the soldiers and hostages, board the Hercules, and fly back to Israel.

Operation Thunderbolt was a go.

Stay tuned for part II.

This article was originally published in July 2020.

COMMENTS

There are on this article.

You must become a subscriber or login to view or post comments on this article.