In the hours and days immediately following the blasts, some speculated the plotters used some sort of cyberattack to cause the pager batteries to rapidly overheat and burst. While lithium batteries have been known to catch fire, something that has happened in checked baggage on airlines (which is why airlines and U.S. Postal Service question you about having such items in your checked luggage or in shipped boxes) they most certainly do not detonate; they deflagrate or burn. Clearly, these were explosions.

Good Possibilities

One way to work around charge diameter is to house your explosives in a highly engineered fashion so the blast wave will move smartly downrange as designed. A great example of explosives requiring very small diameters to function is detonating cord, which is designed to efficiently transfer explosive power against a target such as a door (think breaching), into an explosive (think C4), or to connect a sequence of explosive charges. Detonating cord is rated by the number of grains of explosive material in a given length (a unit of measurement common in the blasting world), so it is easy to calculate: for example, the quantity of an explosive like PETN in one foot of detonating cord. Thus, 50 grain PETN detonating cord (a common size) contains a bit over 3 grams of PETN explosive.

Others have opined some form of liquid PETN might have been sprayed on the batteries, causing them to become an explosive. Notwithstanding PETN is not a liquid explosive, charge diameter makes this impossible, as a multi-micron level coating of high explosive is not going to sustain a detonation wave. However, going back to very old technology, think about how dynamite came to be from Alfred Nobel, the Swedish scientist who patented it and many other explosives (to include blasting caps/detonators). Pouring nitroglycerine into an absorbent inert material (diatomaceous earth or sawdust) does allow for a “stick” or cartridge of dynamite to become an explosive that will sustain a detonation quite well.

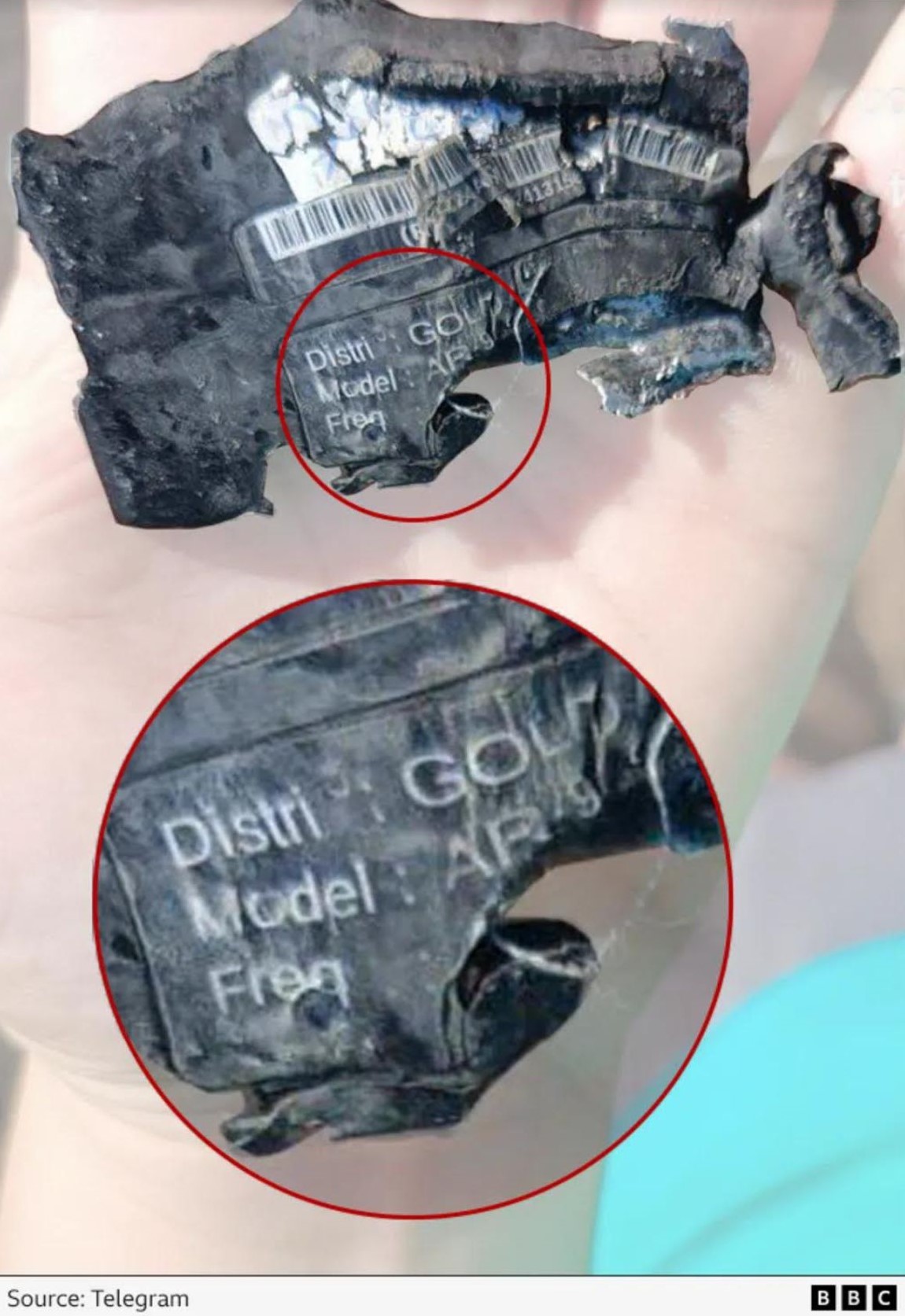

Imagine a smaller-sized cartridge (like a battery pack) has been engineered so a portion of the pack is replaced with PETN and a detonator inserted inside. The outer casing of the battery pack would likely obscure the contents from some x-rays, useful to hide a detonator. There is precedence for this: A 2006 al Qaeda plot to attack United Kingdom originated aircraft with liquid explosives (the origin of the Transportation Security Administration’s 3-1-1 rule) was designed with detonators hidden inside AA sized batteries. According to Lebanese sources who examined the remains of the exploded pagers and conducted controlled detonation of pagers switched off at the time the active pagers exploded, the devices used a lithium ion battery pack, and not removable AA batteries.

How much explosive could an AA sized battery pack hold? Certainly, in the range of several grams, particularly if the pack was designed to still function reliably, even given the likely reduced charge capacity of an adulterated battery pack containing explosives. Given a relatively brief period between delivery of the devices, their distribution throughout the Hezbollah network, and activation, limited battery life might not be detected or could be passed off as a poor-quality battery pack.

Lastly, according to Reuters, a Lebanese source claimed the Mossad “injected a board” into the pagers, and that this “board” was somehow detonated, causing the damage. Explosives can certainly be shaped, and there are known instances of explosives being “printed” through additive manufacturing, more commonly known as 3D printing.

A printed PETN wafer containing several grams of explosive material, covering roughly the interior dimensions of a pager would certainly match the damage visible as a rectangular hole shown on broadcast CBS footage of the attacks. If the board was skillfully engineered, it could appear to be a legitimate internal portion of the pager, needing only a miniaturized detonator to set it off, perhaps disguised so as to appear as an electrolytic (think about a small tube) capacitor.

Based on the size of the available pager container, charge diameter restrictions, and explosives engineering, I think one of the methods above, most likely an adulterated battery pack or 3D-printed explosive, was the culprit.

The Grave Risk to Civil Aviation

One particularly troubling aspect of the pager attacks, which I have heard little to nothing about, concerns the risk to civil aviation from such devices. There are reasons why we have all had to have our laptops, tablets and phones subjected to extra scrutiny for years; either intelligence reporting or actual use of such devices to target commercial aircraft. One attack I am personally well aware of concerned the February 2016 Daallo airlines bombing in Mogadishu, Somalia, which was accomplished through an explosives adulterated laptop. Miraculously, the airplane was able to survive, with the only casualty being the would-be suicide bomber. These screening protocols have been strengthened in recent years.

The world now knows explosives can very effectively be hidden inside pagers and handheld radios. Not only have large chunks of these electronics survived, but it is known that not all of them detonated. In fact, Lebanese officials described doing controlled detonations of recovered devices that were switched off at the time of the explosions, and Hezbollah has stated they are in possession of devices that did not function as designed. Even with a 99% success rate, which would be extraordinary, this means a great many are available for forensic exploitation by Hezbollah and, by extension, Iran. The same technology that was used against Hezbollah terrorists could well be turned against civil aviation. Allow me to explain.

According to a Times of Israel article, Hezbollah is known to have screened their electronic devices, to include sending members into airports to see if standard checkpoint screening technology would detect anything in the devices and trigger alarms. While this claim remains unproven in open-source material, it is consistent with Hezbollah tradecraft. Additionally, had an explosive-filled pager been detected at an international airport, it would have been immediate global news. Unfortunately, this means the technology used to adulterate the pagers with explosives was probably not detectable by current screening devices, likely through a combination of design and forensically cleaning the devices so they could not be discovered through common explosives trace detection technology.

Now, before people run screaming for the exits that a grave vulnerability exists, my observations and background are certainly not unique in the aviation counter-IED detection world. The men and women who study and attack this problem set (and I used to be one of them) are dedicated and skilled professionals, and it is reasonable to believe the U.S. and/or partner nations have obtained one of the pagers, studied it, and have made or are making appropriate changes to screening algorithms and standard operating procedures used in current screening technology. This process of adaptation is not unique, and I am personally aware of threats that caused similar concern and countermeasure activity in the aviation screening world.

Conclusion

The motto of the British Special Air Service is “Who Dares Wins,” and it appears that the Israelis, with a daring plan, struck at Hezbollah in a highly effective way, outright eliminating but certainly also maiming a significant number of Hezbollah players. While this is unlikely to be militarily decisive and may yet provoke a widened Middle East war between Israel and Hezbollah, this innovative attack will clearly have other adversaries thinking about their own technical vulnerabilities. Whether it will also have the unintended consequences of creating a new vector to attack civil aviation remains to be seen, and while aviation security professionals are up to the challenge, we are foolish if we do not at least plan for that eventuality.

COMMENTS