Before the 9/11 the studies on “terrorism” remained confined among a small group of academics who mostly investigated motives and connections with the superpowers ideology and the Cold War. Already in the 1970s there were few University or private institutes operating in the sector, both at the service of some government or independent, who addressed the issue “political violence” in a professional manner. Nevertheless the result of the research was always addressed to those who he had to deal with it and rarely this information passes into the public domain. The investigation into the origin of terrorism embraced the political and military history, social science and even psychology, but never ascended to teaching tout court. After the attack on the Twin Towers, there was a significant change of course and we have witnessed a flowering of institutions, organizations, study groups that have placed as a primary subject of their research Islamist terrorism and Middle Eastern affairs. As a result there was an overproduction of “gray literature”, i.e. material published on the Internet, viewed and downloaded online. From this multiplication of studies and scholars, more or less serious, new professionals have been born once only traceable in spy movies like “Three Days of the Condor”. For example, just referring to the mentioned films, we recall the profession of a young Robert Redford that covered the role of a OSINT researcher (Open Source Intelligence) entangled in one conspiracies hatched by the CIA. In light of the product by historians on terrorism (doubled in recent years) this short paper is intended to try to differentiate some professionalism and delimit and broaden their fields of inquiry without forgetting the largest section, the storytellers who flock to the web pages and newspapers.

Historians

The profession of the historian finds in the pages of Marc Bloch’s “Historian’s Craft” the intellectual base for the delicate work of investigating our past. The scholar of Lyon, who along with Lucien Febvre founded the historical journal “Les Annales,” claimed as the story was the “science of men in time” and that a historian should base the story of the facts on a careful analysis of the sources, whether they oral, both paper. Bloch did not have today’s media and its formation took place on the dusty benches of the archives.

The methodology impressed by Annales Schoolformed generations of scholars, educating them to a certain rigor in the consultation of sources, but especially to a demanding to “distance themselves” from the studied subject and to expose the story free of any opinion: “the historian must understand, not judge.” At this point we realize as a matter than “terrorism” traditional exploratory approach is limited to a few scholars since the same “terrorist history” lends little to the edition of anthologies or summaries old style. If you want to trace in outline a narrative history on terrorism we must look to the valuable work of Alex P. Schmid and Albert J. Jongman, “Political Terrorism,” published in 1988. By scrolling the index we come right in the chapter devoted to the critical analysis of the various texts of “terror and terrorists” and the claims of the two theoretical can be used as a comparison to the developed methodology suggested by Bloch. Alex Schimd relies on a multidisciplinary academic approach using also critical tones than a young literary production, extensive, but actually with a few valid reference. The writer of political violence and terrorism — says Schimd — is generally inexperienced since it has an academic with no direct comparison; and it is here — in his opinion — the essence of the historical work that is not to defeat terrorism, but understand their motives, origins and possible developments. Terrorist organizations

must be studied within their political context, building a parallel with those who fight them. But here comes the real problem. If history has an endless plethora of sources, the most recent events related to political terrorism are cataloged on documentation often unavailable (because it kept secret for obvious security reasons) or altered by government, government agencies and so-called think tanks.

Analysts

The job of a historian cannot be separated from an academic path that leaves little room for improvisation. Sure, there are historians of various kinds whose criterion of analysis of sources is debatable, nevertheless those who perform that job en amateurs shows the limits that make the difference between a historian or a reliable narrator of fairy tales. The same can not be said of a professional figure emerged strongly thanks to terrorism: the analyst. We will see, in fact, as the title of analyst on terrorism is in vogue and therefore subject to many abuses by braggarts who love to pose as such. There should be some key points for a proper distinction from the history. They are two different jobs, but the fact remains that a historian can make the analyst and vice versa. If the historian, however, the temporal units to which investigates are the past,

present and future, in the analyst they appear more narrow and immediate, that is yesterday, today and tomorrow. The most important thing that distinguishes an analyst from a historian, but also a serious analyst by a storyteller is the path that he has done to acquire the information as the road is the analyst as the archive is the historian. Today, unfortunately, we witness interviews or read articles whose authors qualify as analysts without ever setting foot outside the office walls. The analyst’s main task is to store data and then provide his client options. “The forecast or strategic analyst – explains Andrea Margelletti, president of the Italian CESI (Center for International Studies) — presents a number of possibilities for those who must take action on a particular issue, but never makes the final choice for the latter it is exclusively the prerogative of politics”.

Behind the scenes of the analyst’s work there are the so-called think tank agencies, such as RAND Corporation: a giant with headquarters in America and England that providing information for government clients. Although the material executors of the studies are at the height of their fame, the unknown is what these “opinions’ maker” are reliable; RAND, for example, offers its analysts to a customer like the U.S. government and this, perhaps, might somehow impair the objectivity, or at least give a partial address to the survey. Besides, we find the same “Achilles heel” of impartiality in the historian too, when it putting its name to the strong powers.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Journalists

Terrorists act like actors on a stage: follow the script is important, but what sanctions the real success is the audience they can get from the show. Several unsuccessful attacks have become unexpected victories over terrorism since they have obtained an almost total coverage by the media. The media interest was aimed not only the incident in the strict sense, but also a morbid enlargement to other areas of the common life of the victims. We explain better. In recent years the Old Continent has been the subject of a disturbing series of Islamist-motivated attacks that have caused fear and despondency among the affected population. In the face of these events we have established as journalism has repeatedly thrown fuel on the fire certifying what should not be in these cases: loop of images of the post-attack scenario, interviews with victims and their relatives, and finally the invasion of schedules with programs focused on the tragedy of the survivors.

A succession of violent images, sent in the name of the sacred dogma of “all have the right to be informed”; right in the case of terrorism, however, this principle can become a double edged sword, or at least should be subject to more sensible valuations. In particular, the journalist tends to build a sort of transfer between the victim and the survivor by passing it as a possible target future. How to overcome this impasse? Is it correct to muzzle the media over an incident like the one in Berlin or Brussels? In Israel, for example, the relationship between networks and terrorism were the focus of a long debate between the major newspaper titles and the government. So can a government act on the fundamental principle of freedom of the press without looking like a censor system? The answer given by International Institute for Counterterrorism of Herzlya has been proactive and is realistic in the sense that an appropriate review of what was broadcast by the media of certain criminal offenses related to terrorism is the conditio sine qua non to avert the panic by doing so the terrorists.

On journalists weigh in fact, the heaviest responsibility than a historian or analyst because their message gets to a diverse and not specialist audience . To this is then added the increasingly worrying blossoming of “fake news ” in addition to the authentic garbage produced by social media, corrupting the very principle of correct information.

The demon that haunts a reporter takes the name of “news” and this must be diffused before the competitors at the expense of its accuracy: in the time lag between the scoop and its spread, in fact, there is a risk of removing each filter useful to recognize the true from the false. The tensions generated by a terrorist attack, for example, causes a frantic search of the culprit coming even to erroneous conclusions and summary. The hysterical chronicle “hour by hour” of what is happening on the scene of a suicide or an armed commando Islamist attack reels off a series of unverified assumptions about the number of victims and – most dangerous thing — the number of the attackers, hampering investigative work of the forces order.

From this it would seem told reporters more than make information often create disinformation; But remember that there are included in the category noble examples for the correct narration of the facts: journalists that have lost their lives in the battlefields or ending a hostage of some group of cutthroats. In journalism to tell the truth has a very high price and requires professionalism in addressing human also certain subjects, on the other hand, the media spectacle of events is completely free, dangerous and tasteless.

Storytellers

We start by saying that the court’s minstrels and troubadours had their dignity and a precise historical context of great importance. The task of the minstrel was, in fact, to enthrall the spectators with fantastic tales which, however, drew inspiration from everyday life. No for nothing the king listened intently as recited because it was a way to test the mood of the people and know what was going on outside the walls of the palace.

Today, unfortunately, the storyteller has exceeded the fairy-tale and narrative boundaries to go into the detail of the daily news, but also to impose its lively “interpretation of the facts” on social forum. The contemporary “singer” replaced the harp with a computer keyboard that does not produce courtly notes, quite a tedious ticking with either of the nonsense animated by hatred, a profound ignorance and incompetence.

Facebook, more than any other, is the arena in which you compare the “experts” on terrorism, immigration and special forces eager to let others know how good being false and sloppy is. Historians and analysts are of an apportionment on the influence, nevertheless the journalist willingly gives the ascendancy of social evil just because they are what people want to hear. It is a vicious circle in which hinges also politics, now accustomed to the use of the post to convey opinions or results. Well understood, far from demonizing the use of internet, you only want to raise some doubts about the real function of such social news containers confined use — more appropriate — to a mere instrument of gossip.

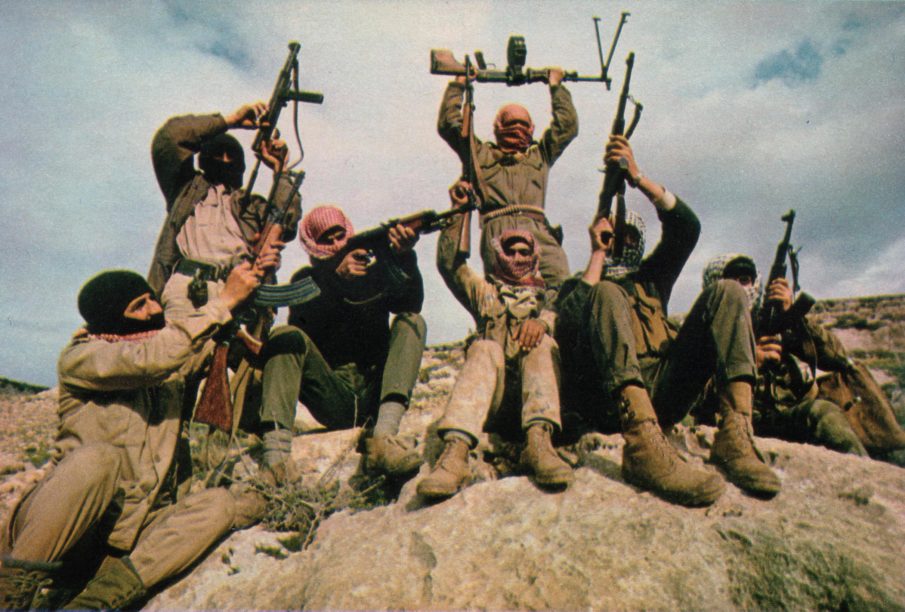

Featured image: In the mountains east of the Jordan River, a patrol from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine punctuates a battle hymn with Soviet, Czechoslovak (vz. 58), and (top left) Egyptian weapons. Early 1969. | By Thomas R. Koeniges (LOOK Magazine, May 13, 1969. p.27) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

COMMENTS