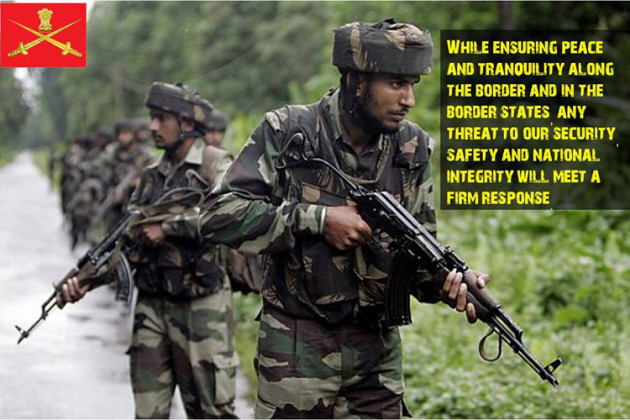

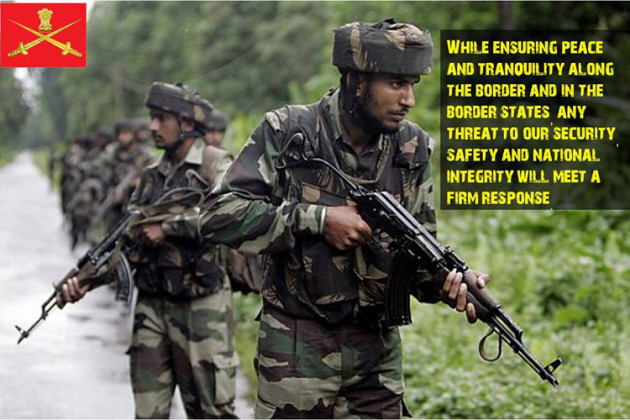

So it seems that the Indian Army’s 21 Para Special Forces commando raid into Myanmar to hunt militants has set off alarm bells in the region, mostly because of the message the Indian government intended to send. The unit was sent across the border partially at the behest of the Burmese government and in response to a June 4 ambush on Indian troops in the area of Chandel, which killed 20.

The retaliatory raid was conducted on June 9, and resulted in at least 20 dead and many more wounded. The militant camp was said to have housed a mix of anti-government fighters, including NSCN(K) militants and those from other groups such as the PLA (People’s Liberation Army of Manipur), UNLF (United National Liberation Front) and the MNRF (Manipur Naga Revolutionary Front). The Indian government has lauded the raid as a success, and hinted that they would continue such “hot pursuit” operations in the fight against future enemies.

According to Minister of State Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore, those incursions could very well include incursions into Pakistan-controlled Kashmir and beyond, if deemed necessary. In response, Pakistan has taken a stance to the effect of, “We are not Myanmar.” (In other words, “Try that crap here and see what happens.”)

So what is this “doctrine of hot pursuit?” Well, for starters, it didn’t begin with an episode of “Cops” or OJ Simpson’s lightning-fast 25 mile-per-hour jaunt down the freeway. The doctrine actually has its roots on the high seas, generally pertaining to the ability of a nation’s navy to pursue a foreign ship that has violated laws and regulations in its territorial waters (in this case, twelve nautical miles from shore), even if that ship flees outside of that zone. The principle is found within Article 111 of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and in Article 23 of the 1958 Convention on the High Seas. For the record, the United States has signed but not ratified the Law of the Sea Convention, but has signed and ratified the Convention on the High Seas.

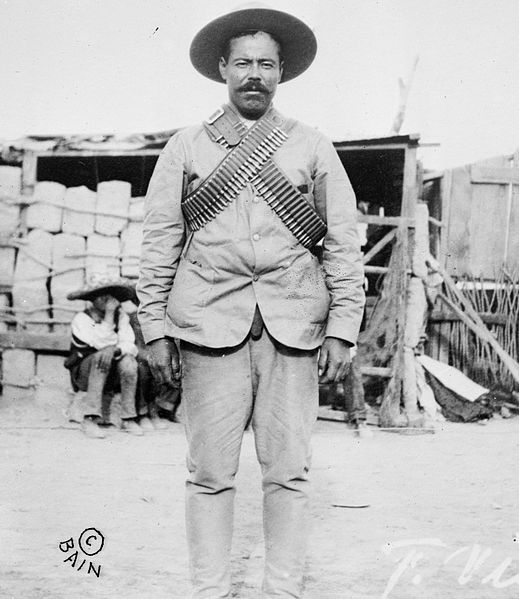

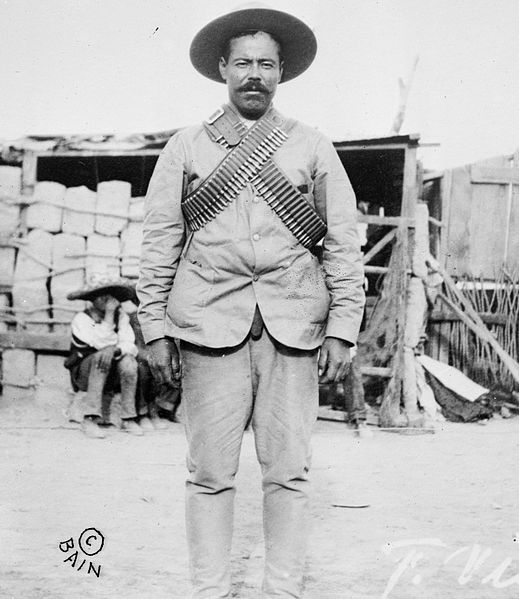

History has shown that when dealing with foreign individuals or armies, nations have overtly or covertly crossed another state’s sovereign borders in pursuit of those suspected of and known to have committed crimes against them. One famous example is the pursuit of Pancho Villa by U.S. forces into Mexico in 1916, made in response to a cross-border raid into New Mexico by Pancho’s “Villistas.” The pursuit, led by then-Brigadier General John J. Pershing, failed, and Villa escaped. However, the operation proved that the United States, among others, was not above ignoring the laws of sovereignty to protect its citizens.

Another example was the 1960 international pursuit and capture of former high-ranking Nazi official Adolf Eichmann by Israeli agents in Argentina. Almost ending in disaster, Eichmann’s apprehension was widely considered a violation of international law and Argentine sovereignty, but repercussions for the operation never went beyond more than public condemnation. Ironically, neither of the cases invoked the principle of “hot pursuit” to justify their cross-border activities.

It is rumored that during the Korean War, special operations teams crossed the Yalu River and entered Chinese territory to conduct sabotage operations. As of the time of this writing, I have been unable to verify these claims (but stay tuned). What is known is that U.S. fighter aircraft routinely (though not exactly legally) crossed the Korea-China border at the Yalu River in pursuit of enemy air assets. Officially frowned upon by headquarters, local commanders generally turned a blind eye to the practice as long as it produced kills. During the Vietnam War, special operations teams were routinely run across the border in pursuit of VC and North Vietnamese forces, and aerial bombing and mining missions were at times authorized to decimate enemy forces and deny use of supply routes such as the Ho Chi Minh trail.

Soon after the invasion of Iraq in March 2003, it was suspected that the majority of the foreign-born insurgents showing up in Iraq were entering the country through the Syrian border. Warnings were issued to the Assad government to stop the flow of these suicide bombers, but it was not taken seriously. Experts called on the U.S. military to raise the ante with Damascus by conducting cross-border raids by Special Forces or targeted air attacks to hunt down jihadis on Syrian soil, arguing that such a strike would be justified under international law and the principle known as “hot pursuit.”

Turkish officials had, in the past, invoked this doctrine to justify cross-border incursions into northern Iraq to pursue Kurdish rebels, and many believed that the U.S. was more than justified as well. But some international legal scholars dispute whether the doctrine could be applied in this case and refute the notion that either U.S. or Turkish forces could justify cross-border incursions, however limited in scope.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

So how do governments get around the principle of sovereignty when it comes to hot pursuit? Under international legal norms on state responsibility, and UN Security Council Resolution 1373, passed shortly after the events of 9/11, state sovereignty implies a duty to control one’s territory. That is, a government has an obligation not to allow its territory to be used by non-state actors—or terrorist organizations—to carry out armed attacks against its neighbors.

In the case of U.S. raids into Syria in pursuit of foreign fighters, the burden was on the U.S. government to prove that the Syrian government had failed in this duty by failing to prevent these foreign actors from crossing into Iraq and carrying out attacks against U.S. troops. In response to this failure, it was argued, U.S. special operations forces should then have the legal right to “pursue” these foreign jihadis, even if they flee back into Syrian territory.

On the evening of the 27th of October 2008, a fleet of helicopters carried U.S. commandos across the Iraq-Syria border on a controversial operation. Four helicopters, believed to be MH-60 Black Hawks operated by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, inserted a special operations team into the border area of Abu Kamal. The team’s target was a building site situated at the village of Sukkariyeh, suspected of being the base of operations for one Badran Turki Hashim al-Mazidih, also known as Abu Ghadiya, an al-Qaeda commander responsible for smuggling large quantities of guns, money, and foreign fighters into Iraq.

In this case, it is believed that the Syrian government, who viewed Abu Ghadiya as a common enemy, approved of the operation and even provided intelligence support. Ultimately, what was believed to have started as a snatch-and-grab op went the way of many and turned into a full-on firefight, with Ghadiya being killed (his body was exfil’ed along with the team) as well as seven Syrian fighters. Tactically a success, the unforeseen “loudness” of the operation led to the Syrian government lodging a formal protest. Go figure.

Since that time, the United States and other nations around the world have deemed it necessary and justifiable to invoke the right to engage in “hot pursuit” to bring perceived enemies to justice (see Jack Murphy’s article on the topic here). The court of world opinion may, in some cases, condemn the act, applaud it in others, and in many, remain silent. But in the end, governments will (though not always) do what they see fit to protect its citizens, even if that means chasing the bad guys into their neighbor’s yard and house to get them.

COMMENTS