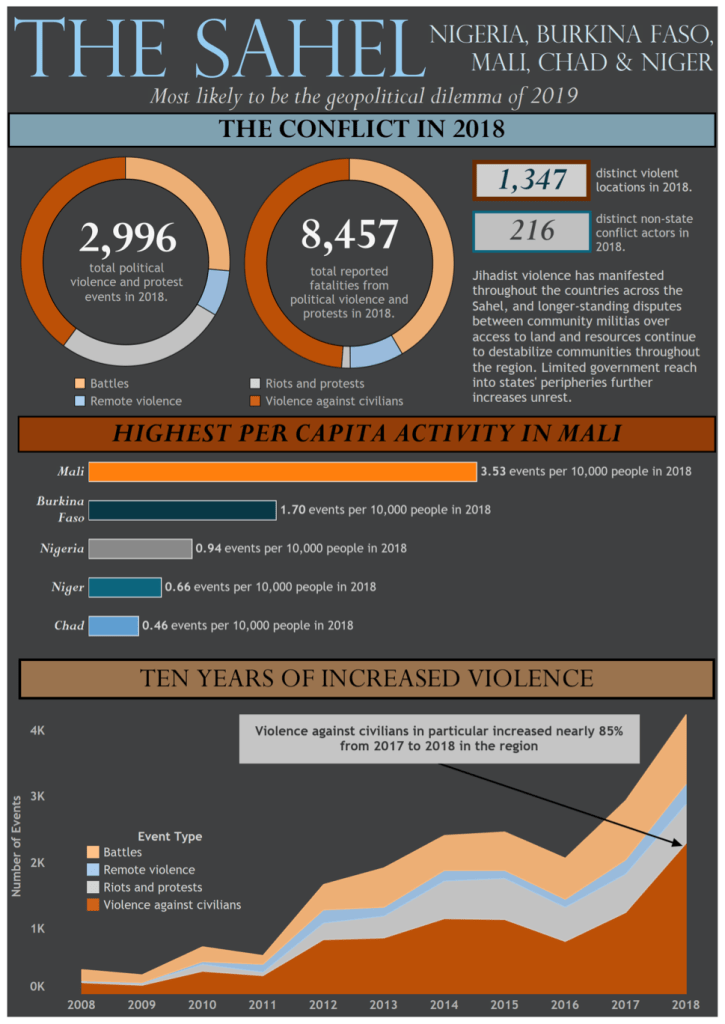

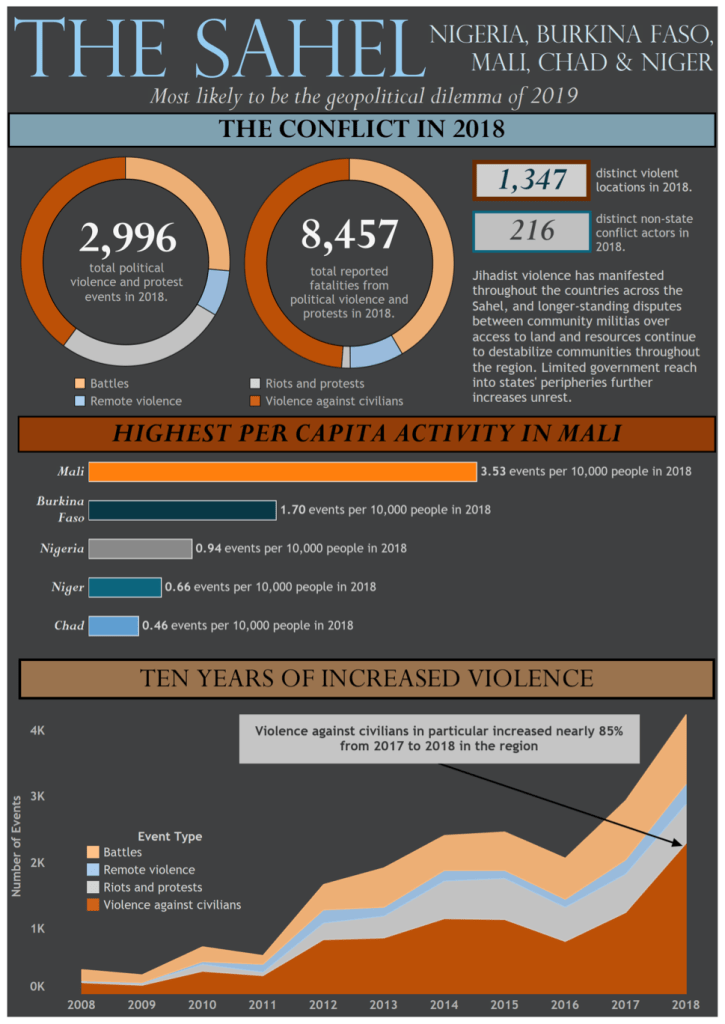

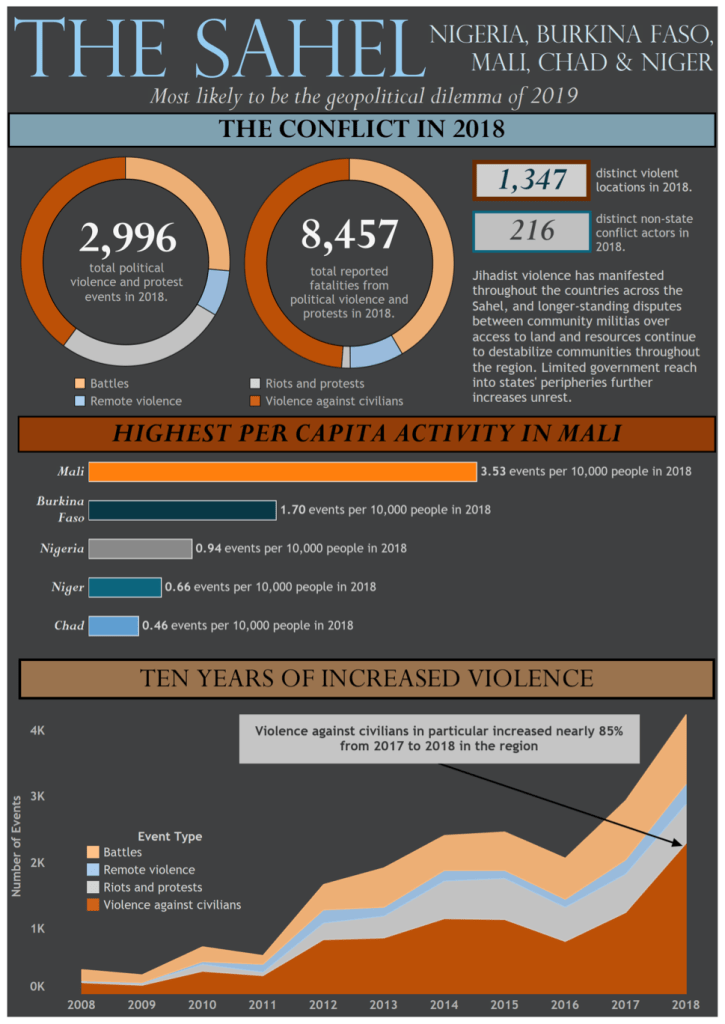

Terrorist attacks are on the rise in the Sahel region of Africa, particularly in Burkina Faso and Mali. Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) has claimed responsibility for many strikes against the countries’ security forces. This would suggest that the ISGS has found a foothold in both states and is growing stronger by the week. The ISGS was first thought to be a relatively new splinter group originating from Al-Mourabitoun, based out of Mali, but new findings reveal that we can trace the group back to 2017, when the Islamic State first established a presence in Burkina Faso.

Burkina Faso is set to become a stomping ground for the Islamic State and its old rival al-Qaeda as it faces a renewed surge of attacks. Various armed groups have taken advantage of the turmoil and the situation on the Mali-Burkina Faso border. Toward the end of last year, ISGS and various criminal groups have turned the once-beautiful territory into a place of fear and horror.

Back in 2015, Burkina Faso was constantly apprehensive of the violence in Mali pouring across its borders. In 2017 the country faced a surge in terrorist attacks on Burkina Faso soil, predominantly because of their homegrown terrorist group Ansar ul Islam. But not all armed attacks were the work of terrorists. Burkina Faso continues to face security issues including organized crime, rural banditry, and coordinated cross-border attacks.

Armed bandits have run cross-border operations between Burkina Faso and Mali for years. However, since 2018, this violence has grown in intensity, with repeated assaults made against law enforcement and military positions and patrols—a noticeable change from the past when violence was restricted to predominately petty banditry. Recent attacks have resulted in fatalities, injuries, and considerable material damages to government facilities.

The targets they have selected and the way in which these groups have conducted their strikes make it unlikely that this is merely banditry. A broader movement in the region suggests a solidifying nexus between radical militancy and banditry, an alliance of convenience with mutual benefits (bandits hijacking the cause of terror groups for financial gain and influence). Terror groups may co-opt existing criminal networks by offering more advanced, heavier hardware and currency in order to make inroads where they have a poor or nonexistent support base and presence. Doing so increases their area of operations. Armed bandits may also provide manpower and logistical help, enabling the implantation of militant groups in relatively uncharted terrain. From the viewpoint of armed bandits, rallying behind militant Islamist groups could selfishly enable an unmitigated campaign of plundering and pillaging.

Burkina Faso is currently experiencing the same situation seen in Mali when al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) set up shop within their borders. Al-Mulathameen (“Masked Men Brigade”), also known as the al-Mua’qi’oon Biddam (“Those who Sign with Blood”)—commanded by the famous Mokhtar Belmokhtar (The One-Eyed, The Uncatchable)—has operated in multiple countries: Algeria, Niger, Libya, and Mali. Although the group operated independently, it took orders and swore allegiance to AQIM, maintaining its main base of operations in Mali. One of the largest attacks this group claimed responsibility for was an attack on an Algerian gas plant where more than 800 hostages were taken and nearly 40 were killed. Belmokhtar justified these actions based on the French-led intervention in Mali, which had happened a couple of days before.

Terrorist attacks are on the rise in the Sahel region of Africa, particularly in Burkina Faso and Mali. Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) has claimed responsibility for many strikes against the countries’ security forces. This would suggest that the ISGS has found a foothold in both states and is growing stronger by the week. The ISGS was first thought to be a relatively new splinter group originating from Al-Mourabitoun, based out of Mali, but new findings reveal that we can trace the group back to 2017, when the Islamic State first established a presence in Burkina Faso.

Burkina Faso is set to become a stomping ground for the Islamic State and its old rival al-Qaeda as it faces a renewed surge of attacks. Various armed groups have taken advantage of the turmoil and the situation on the Mali-Burkina Faso border. Toward the end of last year, ISGS and various criminal groups have turned the once-beautiful territory into a place of fear and horror.

Back in 2015, Burkina Faso was constantly apprehensive of the violence in Mali pouring across its borders. In 2017 the country faced a surge in terrorist attacks on Burkina Faso soil, predominantly because of their homegrown terrorist group Ansar ul Islam. But not all armed attacks were the work of terrorists. Burkina Faso continues to face security issues including organized crime, rural banditry, and coordinated cross-border attacks.

Armed bandits have run cross-border operations between Burkina Faso and Mali for years. However, since 2018, this violence has grown in intensity, with repeated assaults made against law enforcement and military positions and patrols—a noticeable change from the past when violence was restricted to predominately petty banditry. Recent attacks have resulted in fatalities, injuries, and considerable material damages to government facilities.

The targets they have selected and the way in which these groups have conducted their strikes make it unlikely that this is merely banditry. A broader movement in the region suggests a solidifying nexus between radical militancy and banditry, an alliance of convenience with mutual benefits (bandits hijacking the cause of terror groups for financial gain and influence). Terror groups may co-opt existing criminal networks by offering more advanced, heavier hardware and currency in order to make inroads where they have a poor or nonexistent support base and presence. Doing so increases their area of operations. Armed bandits may also provide manpower and logistical help, enabling the implantation of militant groups in relatively uncharted terrain. From the viewpoint of armed bandits, rallying behind militant Islamist groups could selfishly enable an unmitigated campaign of plundering and pillaging.

Burkina Faso is currently experiencing the same situation seen in Mali when al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) set up shop within their borders. Al-Mulathameen (“Masked Men Brigade”), also known as the al-Mua’qi’oon Biddam (“Those who Sign with Blood”)—commanded by the famous Mokhtar Belmokhtar (The One-Eyed, The Uncatchable)—has operated in multiple countries: Algeria, Niger, Libya, and Mali. Although the group operated independently, it took orders and swore allegiance to AQIM, maintaining its main base of operations in Mali. One of the largest attacks this group claimed responsibility for was an attack on an Algerian gas plant where more than 800 hostages were taken and nearly 40 were killed. Belmokhtar justified these actions based on the French-led intervention in Mali, which had happened a couple of days before.

Belmokhtar was just a smuggler—an outlaw—before his association with AQIM. AQIM needed his network to increase their range of operations, so they provided Belmokhtar with the arms required for the Algerian gas plant mission (most likely men as well). This strengthened Belmokhtar’s influence and area of operations. With the assistance of AQIM, he became one of the most infamous characters in the Sahel region. It’s also worth noting that Belmokhtar declared the attack on the gas plant was in response to the French-led operation in Mali. With this statement he amplified the word of AQIM and facilitated their propaganda operation. A symbiotic relationship if ever there was one.

Burkina Faso should look hard into the connection between these criminal networks and terrorist groups operating along its borders and should maximize their efforts to handle these groups as promptly as possible.

COMMENTS

There are on this article.

You must become a subscriber or login to view or post comments on this article.