If you want a squeaky clean Christmas story, grab two fingers of whiskey and go find a pine tree and a warm fire. There are plenty of those tales to be told.

If you want the real thing, the kind with frozen mud, shattered steel, and a nineteen-year-old farm kid stepping off a half-track to silence German guns, then you are looking for Private James Richard Hendrix. His Medal of Honor action came on December 26, 1944, the day after Christmas, during the final shove to break through to the encircled Americans at Bastogne.

Many of us know the sting of being thousands of miles away from our homes and loved ones during the Christmas season. James was no exception.

Before the Army: Lepanto, Arkansas, and a Childhood Built on Work

Hendrix was born August 20, 1925, in Lepanto, Arkansas, the son of sharecroppers. His family did not have the luxury of long school days or soft hands. He left school young and went to work in the fields alongside his parents like so many of his peers of the day.

That kind of upbringing does something to a person. It teaches you how to keep moving when you are tired. It teaches you how to be useful when the weather is bad, and nobody cares about your excuses. In Hendrix’s case, it also meant he grew up hunting, learning the quiet mechanics of marksmanship long before the Army handed him a weapon.

Joining Up: Drafted Into a World on Fire

In 1943, Hendrix was drafted into the U.S. Army at age 18. There is no romantic recruiting poster needed here. The war was eating manpower, and Uncle Sam came calling.

He went through training and ended up in Company C, 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, 4th Armored Division. The 4th Armored Division would become one of Patton’s hard-driving spearpoints in Europe, the kind of outfit that lived on speed, aggression, and the belief that hesitation got people killed.

The Road to the Bulge: Learning the Job in Patton’s Wake

By mid-1944, Hendrix was in the European meat grinder with the 4th Armored Division, pushing through France as the Allies fought out of the Normandy hedgerows and into open country. Armored infantry life was not glamorous. It was riding, dismounting, clearing, holding, and doing it again until your nerves felt like stripped wire.

This matters because Hendrix’s Medal of Honor moment did not appear out of nowhere. Hendrix had already been shaped by months of hard movement and harder contact. He was learning what most soldiers learn through time: the enemy gets a vote, and the terrain is always trying to kill you.

December 26, 1944: Christmas Leftovers and 88mm Guns

The Battle of the Bulge turned the Ardennes into a wintry death trap. Bastogne was surrounded, and relief was not on the holiday wish list. There was a mission with a clock on it.

On the night of December 26, 1944, near Assenois, Belgium, Hendrix was with the lead element in the thrust to break through to Bastogne when the column was hit by enemy artillery and small arms fire. He dismounted and advanced on two 88mm guns, using rifle fire and sheer nerve to force the crews into cover and then into surrender.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Later, he again left his vehicle to help two wounded Americans pinned down by machine gun fire. He silenced two machine guns and held off the enemy until his wounded could be evacuated.

Then, as if the night had not collected enough debts, Hendrix rushed to a soldier trapped in a burning half-track, pulled him out, and extinguished his flaming clothing, saving the man’s life.

Here is the Christmas tie-in. While the world back home was still in the glow of December 25, Hendrix was spending December 26 in the cold arithmetic of survival, turning seconds into lives saved.

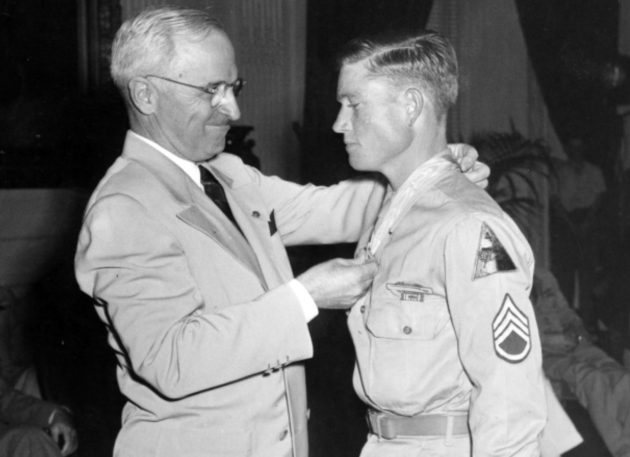

The Medal, the White House, and Staying in Uniform

Hendrix received the Medal of Honor from President Harry S. Truman at the White House on August 23, 1945. The photo is famous for a reason: a young soldier from Lepanto standing in the national spotlight, carrying the weight of an entire night in Belgium.

After World War II, Hendrix stayed in the Army and joined the paratroopers. In September 1949, during training, his parachute failed to open, and he survived an estimated 1,000-foot fall. Truman later met him again in connection with that incident, which sounds like the sort of unbelievable twist you would cut from a movie script for being too much, except it really happened.

Hendrix served in the Korean War and remained in uniform for a career, retiring in 1965 as a master sergeant.

After the Army: Quiet Years, Heavy Legacy

After leaving active service, Hendrix lived quietly in Florida. He died on November 14, 2002, in Davenport, Florida, and was buried at Florida National Cemetery in Bushnell.

He left behind a family and a record that does not need embellishment. It stands on its own.

A sharecropper’s son, drafted into a global war, who did not wait for permission to do what had to be done.

—

** Editor’s Note: Thinking about subscribing to SOFREP? You can support Veteran Journalism & do it now for only $1 for your first year. Pull the trigger on this amazing offer HERE. There is still time, but, like the holiday season, this offer won’t be around forever.– GDM

COMMENTS