A zigzagging, roundabout, approach route west of the Solomon Islands was plotted, adding many extra miles to the route so the Lightnings would appear to be simply passing by instead of taking a direct route from Guadalcanal. P-38 pilots were handpicked for the mission from three different fighter squadrons, departing from Kukum Field (“Fighter 2”) on Guadalcanal, with a calculated intercept point over Empress Augusta Bay (named for Empress Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, the last German empress and queen of Prussia, married to Kaiser Wilhelm II. The island was part of the German Empire from 1899 to 1920, and Empress Augusta died in 1921, west of Bougainville, at 9:35 AM, well before Yamamoto’s projected landing time at Ballalae.

They took off from Kukum Field at 7:10 AM on Palm Sunday morning, April 18, 1943, and experienced immediate problems when two of the four P-38s in the killer flight had to drop out of the mission due to mechanical problems, so two of the other pilots were substituted, instead.

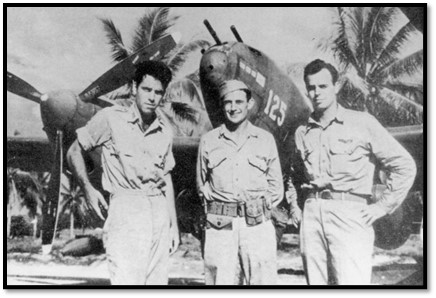

Now, the killer flight consisted of Captain (later Colonel) Thomas G. “Tom” Lanphier, Jr., First Lieutenant (later Colonel) Rex T. Barber, his wingman, First Lieutenant Besby F. “Frank” Holmes, leading the second element, and First Lieutenant Raymond “Ray” K. Hine, who was Holmes’ wingman. After forming up over the airfield, they finally departed from Guadalcanal Island at 7:30 AM, headed in a westerly direction.

Major John Mitchell led the formation of 16 remaining Lightnings at ultra-low altitude, carefully navigating with his GI wristwatch and special Navy compass at 250 miles per hour. In the heat of the sunny, greenhouse cockpit, which could not be opened to allow fresh air inside, and lulled by the engine drone on this longest, fighter-intercept mission of the entire war, he was trying very hard not to fall asleep. They were flying so low that some of the other pilots counted sharks to keep their minds occupied during the long, monotonous flight of more than two hours in the tropical heat.

Meanwhile, at Rabaul, Admiral Yamamoto, attired in an ordinary, dark-green, combat uniform in solidarity with the Japanese troops stationed there, but with his service ribbons on his chest, and wearing white, cotton gloves and his handcrafted, 1934 Sadayoshi Amada katana at his waist, strapped into a spare, crewmember seat as a passenger aboard a green, G4M1 “Betty” twin-engine, naval bomber, tail number 323, and took off precisely at eight o’clock AM.

But he was followed by Chief of Staff Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, aboard a second G4M1 bomber, tail number 326, together with part of Yamamoto’s staff, so there were now two bombers, escorted by six A6M2b Zero naval fighters, leaving Rabaul exactly one half-hour after the P-38s departed from Guadalcanal, and maintaining a flight altitude of 6,500 feet, enroute toward Ballalae Airfield, with clear skies all the way.

Major Mitchell’s timing was absolutely perfect, and the 16 Lightnings arrived over Empress Augusta Bay precisely at 9:34 AM, with just one minute to spare before the Japanese aircraft were due to arrive. They didn’t want to appear to be waiting, in a cold, calculated ambush, so it had to look like a chance encounter, or pure luck, in order to protect the Top-Secret, codebreaking effort.

As they entered the bay area at wavetop altitude, there was a low-level haze, so Mitchell led his raiders up to 2,000 feet, and Yamamoto’s eight aircraft began slowly descending to 4,000 feet as they flew closer toward their destination. The six Japanese Zero fighter escorts were 1,500 feet higher than the two bombers, and offset behind them at the four o’clock position, arranged in two V-shaped formations of three fighters each. Yamamoto’s bomber was slightly ahead and to the right of Ugaki’s.

Sharp-eyed First Lieutenant Douglas S. “Doug” Canning, nicknamed “Old Eagle Eyes,” spotted the enemy formation first, calling out on the radio, “Bogeys! (‘Unidentified aircraft!’) Eleven o’clock high!”

Preparing for aerial battle, the American P-38 pilots then jettisoned their external fuel tanks for extra speed and maneuverability, having just enough remaining fuel for no more than 10 to 15 minutes of combat, and the long trip back to Guadalcanal. They expected to see 50 to 75 Zero fighters from Kahili Airfield rising up to protect Yamamoto, but none of them had materialized yet, and Mitchell’s top-cover section of 12 P-38Gs firewalled their throttles, climbing swiftly to 18,000 feet to fend off the mass of Zeros that was certain to arrive any minute now.

But, in the killer flight, Frank Holmes’ drop tanks failed to detach, making him slow and vulnerable, so he and Ray Hine turned westward, back over the sea, avoiding direct contact until Frank could roughly shake his fuel tanks loose.

Major Mitchell was alarmed to see two enemy bombers instead of just one, especially now that his killer flight was temporarily down to only two fighters, Lanphier’s and Barber’s. Now they’d have to shoot down both bombers to be certain of killing Yamamoto, because there was no way to know which one was his personal transport.

“Alright, Tom,” Mitchell radioed hastily. “Go get him. He’s your meat.”

Now, Tom Lanphier, brash and ambitious, with four aerial victories to his credit already, plus the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Silver Star, and soft-spoken Rex Barber, his wingman, with three confirmed, aerial victories to date, and the Silver Star, suddenly found themselves alone against eight Japanese naval aircraft, with a minimum of fuel remaining, and a seemingly-impossible task ahead.

When they were about a mile in front of the bombers, the escorting Zeros spotted the P-38s and dropped their own external fuel tanks to prepare for battle. The first “Betty” bomber, with Admiral Yamamoto aboard, dove eastward toward the treetops for safety, while Ugaki’s bomber turned seaward over the bay.

Lanphier and Barber initially climbed to engage the six Zeros, but quickly remembered that their real targets were the twin G4M1 bombers, so Lanphier, flying his assigned P-38G, zoomed upward toward the Zeros, engaging three of them head-on, hitting one of them, which he later claimed as an aerial kill, and breaking up their escort formation as he reached an altitude of 6,000 feet.

This gave Rex Barber the opportunity to go after the two naval bombers, flying a borrowed P-38G, nicknamed “Miss Virginia,” with the number “147” on the nose in yellow numerals. His own assigned aircraft, nicknamed “Diablo,” was currently down for maintenance.

Barber banked steeply to the right to tuck in behind the bombers, momentarily losing sight of them behind his upraised, left wing, but suddenly he was directly behind one of them, Yamamoto’s, and he began firing his four .50-caliber machine guns and single 20mm cannon into its right engine, rear fuselage, stabilizers, and tail section, closing the engagement range to less than 100 feet as heavy, black smoke, flames, and metal debris from the rudder streamed back toward him.

At this same moment, Tom Lanphier had reached the top of a half-loop maneuver overhead, and looked down to see three Japanese Zeros chasing Barber’s P-38, which was directly behind one of the bombers, and making repeated, firing passes at him. Lanphier dove back down and banked around for a desperate, long-range, right-angle burst against the fleeing bomber from its right side, briefly firing his guns.

With its right engine totally engulfed in bright, orange flames, the G4M1 bomber snap-rolled violently to the left as Barber narrowly avoided a mid-air collision with it, and the bomber went down into the dense jungle nine miles southwest of the mining town of Panguna on Bougainville Island. Barber didn’t witness the crash himself, but noticed thick smoke billowing up from the jungle.

Lanphier then broke radio silence for the first of three times on this ultra-secret mission, breaching operational security to transmit, “I got a bomber. Verify him for me, Mitch. He’s burning.” Yet, no one witnessed Lanphier shooting the Betty down, so it was an unverifiable claim. Rex Barber, however, properly maintained strict radio silence for the entire mission.

Meanwhile, two P-38G Lightnings from Major Mitchell’s top-cover flight zoomed down just in time and cleared the three Zeros off of Barber’s tail as he now headed back toward the coastline at treetop level, taking evasive action. Rex was aware that there was still another bomber in the area, and they did not know which one contained Admiral Yamamoto, their assigned target.

Out over Empress Augusta Bay, Barber spotted the second bomber, low over the water, attempting to dodge an attack by Frank Holmes, who had finally shaken his drop tanks off. Holmes damaged the right engine of the G4M1, which emitted a white vapor trail, but he and Ray Hine came in so fast from behind that they overshot the stricken bomber toward the south.

Barber attacked it next, from so closely behind that its metal debris hit his own right wing, tearing out the turbo-supercharger and badly denting the central nacelle. The bomber descended and crash-landed in the water, with Vice Admiral Ugaki and two others miraculously surviving the fiery incident.

Barber, Holmes, and Hine were then attacked by the Zeros, with Barber’s aircraft riddled by 104 bullet holes. The top-cover flight briefly engaged the Zeros without scoring any kills, and Ray Hine’s P-38G disappeared during this fight, last seen trailing vapor from his right engine, with three Zeros behind him. Running very low on fuel by this point, the P-38s had to break off contact and return to base in groups of one or two. Everyone made it back by noon, except for Ray Hine, who was never seen again.

Later, Tom Lanphier and Rex Barber, who had both filed separate claims for downing Yamamoto’s bomber, were each officially credited with a half-kill against Yamamoto, while Holmes and Barber received similar half-credits for shooting down Ugaki’s bomber. This led to a huge controversy and dispute that lasted for many years, and was never formally resolved. Only Ray Hine went down in the dogfight, probably killed by Kenji Yanagiya, who reported shooting down a vapor-streaming, P-38 straggler.

Admiral Yamamoto’s body was recovered the very next day in the deep jungle three-quarters of a mile south of the Jaba River, by a Japanese search-and-rescue party. The admiral, still strapped into his crew seat, had been thrown clear of the wreckage, and was propped upright under a tree, probably placed there reverently by a wounded and dying crewmember. His white-gloved hand was grasping the hilt of his custom katana.

A post-mortem examination of the body revealed that he was hit from behind by two .50-caliber bullets as he sat facing forward in the aircraft, turning his head to the left as he heard the loud gunfire behind his bomber. One bullet pierced the back of his left shoulder, and the other entered the left side of his lower jaw, exiting above his right eye and killing him instantly.

Subsequent investigations reported that “all visible gunfire and shrapnel damage was caused by bullets entering from immediately behind the bomber.” These grim details were concealed from the Japanese public “on orders from above.”

This was confirmed by the testimony of Japanese fighter pilot Kenji Yanagiya, who personally witnessed Yamamoto’s lead bomber crash within 20 to 30 seconds after being hit from behind by a P-38 Lightning. The other Zero pilots all died in combat later in the war. The only Lighting that was ever positioned behind that bomber was Rex Barber’s, so the forensic evidence, ground investigations, and eyewitness testimony all fully support Barber’s wartime claim for shooting down Admiral Yamamoto.

Six months after the highly-successful mission, in October 1943, TIME magazine published an article about the operation, with unauthorized details that threatened to compromise military codebreaking efforts, although the Japanese never caught onto the fact that their JN-25D code was broken by the Americans, so they continued to use it throughout the rest of the war. But the U.S. Navy was outraged at this flagrant breach of security, and the sudden media attention to this very sensitive mission. As the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw astutely observed, “The only secrets are the secrets that keep themselves.”

Major John W. Mitchell and each of the four shooters had already been nominated for the Medal of Honor, America’s highest award for valor, by that time, but that would have created unwanted publicity for the Top-Secret mission, which was already on the verge of public release, so their medals were downgraded to the Navy Cross instead, the Navy’s second-highest award, which was still extremely unusual for Army pilots, but it was a Department of the Navy operation, after all.

Rex Barber’s citation reads, in part: “Presenting the Navy Cross to First Lieutenant (Air Corps) Rex Theodore Barber…United States Army Air Forces, for extraordinary heroism while serving as pilot of a P-38 fighter plane…attached to a Marine Fighter Command…on 18 April 1943. Participating in a dangerously long, interception flight, First Lieutenant Barber…struck fiercely, destroying one Japanese bomber at such close range that fragments from the explosion lodged in the wings of his plane…His brilliant airmanship and determined, fighting spirit throughout a daring and vital mission were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Armed Services.”

Admiral Yamamoto’s violent death by targeted killing was an enormous blow to Japanese military morale during World War Two, but had quite the opposite effect in the United States, boosting American morale immeasurably, where it was viewed as completely justifiable revenge for the 3,546 Americans killed or wounded in the Japanese surprise attack at Pearl Harbor. After his death, Japan never again won a major battle in the Pacific Theater of Operations.

On August 15, 1945, Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, who had survived the Yamamoto raid, strapped on a wakizashi (short, samurai sword) given to him by the late admiral, climbed into the back seat of a Yokosuka D4Y “Judy” dive bomber, and disappeared on a kamikaze suicide flight at 7:24 PM. Ugaki was likely shot down by American anti-aircraft fire, with his body found and buried on Iheya Island, 20 miles north of Okinawa. The Japanese Empire posthumously awarded him the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun.

The United States government did not officially acknowledge the full story of Operation Vengeance until September 10, 1945, after the war was over, when many newspapers published an Associated Press account. It’s a dramatic, true tale of code-breaking espionage, highly precise planning and navigation, determination and heroism in aerial battle, and the sheer audacity to penetrate deeply behind enemy lines in order to strike a vital leadership target of enormous significance to the overall war effort.

COMMENTS