So, former 3/75 Ranger and author Nick Irving just nailed a major television deal. Release the OPSEC hounds! Surely there is tomfoolery afoot! Any veteran of a special operations unit that has done work in the limelight can verify that “stepping out of the shadows” is one of the hardest things you will do. Whether it is writing a book or becoming involved in the entertainment industry, you not only open yourself up to the public at large to rip you apart, but also your fellow brothers and sisters in arms.

How much heat you take largely depends on how you go about your business. For example, we have all seen what happens when you blatantly disregard non-disclosure agreements. But even if you do everything “right,” you will still catch a little shrapnel. You will be asked, “Whatever happened to the silent professional?” or, “Since when do (insert any SOF unit but NSW) write books/make movies?” You will, at times, seriously contemplate whether what you are doing is worth it all. As someone who has written two books, have a third nearly done, and writes for four different online publications regularly, I can say I have felt that heat and sympathize with guys like Nick Irving, Leo Jenkins, Jack Murphy, and a host of others who have had it much worse than me.

But the question begs to be asked: Are we supposed to be “quiet” professionals, or “silent” professionals?

First, let’s lay down some context. Writing books or making movies is not a post 9/11-generation issue. Earnest Hemingway, a World War One veteran, became world renowned as a journalist and author. A plethora of World War Two veterans wrote books and made movies (Audie Murphy anyone?), and it continued from there. If you served in the past two decades, chances are you probably have read one of the many Vietnam memoirs that have been published, and one of those books may have even influenced you to join in the first place. With that being said, just because it’s been done before doesn’t mean its right. Right?

While I was serving in 1st Ranger Battalion, I was very much against anything that put us in the limelight. We were told not to tell people we were Rangers, not to talk about work, and to generally keep our mouths shut. The 75th Ranger Regiment very appropriately has the reputation as the most OPSEC-aware unit in the Special Operations Command. I thought it was stupid that 1/75 marched in a parade on St. Patrick’s Day, that we held our change-of-command ceremonies in a public park, and that we invited local news to our awards ceremonies.

I thought it was completely against everything we had been taught as young Rangers. I mean, I was once smoked for over three hours and had my phone/computer privileges taken away on my first deployment (Iraq) for two weeks because, get this, I told my dad we used Remington 870s over the phone. Gasp! And I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw that Regiment had it’s own Facebook page, especially after seeing Rangers RFS’d (Released For Standards) over accessing that website overseas. So, to say that I had OPSEC pummeled into me is an understatement.

I first started to consider different opinions when then Regimental Sergeant Major Rick Merritt visited us in Salerno on my fifth deployment. As is the routine with any visiting VIP, we gathered both strike forces into the JOC for him to talk to us. In the course of his speech, he talked about how Regiment had a PR problem, and we needed to fix it. He talked about the need, not the want, but the need for Regiment to appropriately balance PR and OPSEC. It directly affects everything from recruitment to funding, and everything in between.

That was the first chip in my “don’t-talk” ethos. Shortly after that deployment, I left 1/75 to be a detailed recruiter up in Syracuse, NY. I saw firsthand the massive disconnect between the military and the rest of America. I saw how parents viewed our service and us. I saw how prospective recruits viewed the Army, and more specifically, Army SOF units. To say that it was disheartening would be a severe understatement.

As someone who owes everything to Regiment in particular, and the Army in general for making me who I am today, I felt a need to contribute in some way. I had now performed a 180°, and saw how damaging complete silence can be. It’s “quiet” professional, not “silent” professional, and I began to make that distinction. Leave your ego at home, and bring credit to the unit and not yourself. That’s a quiet professional.

At the time, the Army was literally paying me to “tell my Army story,” and doing so accurately and without hubris works on many different levels. In a nation scarred by Abu Ghraib and overburdened with the uglier side of war on the 24-hour news cycle, it is on us, and only us, to set the record straight.

What was my path into the publishing world? Well, I started writing by accident. I never knew I could write until I was half drunk one night and banged out what I would later title ‘The Ranger’ in a fit of nostalgia. I initially didn’t want any credit for it, and shared the short piece on Facebook as if someone else wrote it. It wasn’t until months later that I started to claim it as my own when I saw others plagiarizing it and changing the original words.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

My first book was published by St. Martin’s Press, and it was basically the most accurate version of a Ranger knowledge book (not to be confused with the Ranger handbook) that I could make. It included only open-source material, and was meant to help the prospective Ranger or the Ranger who was getting ready for a promotion board. The idea for this book came from my experience as a recruiter, running a side program specifically to help kids get into Regiment or SF.

I successfully put 16 guys into the Ranger Regiment, with only two (that I know of) being RFS’d to date. I saw firsthand from talking to some of their team leaders and squad leaders how much their leadership appreciated having a new guy who knew his shit already so that they could focus on the stuff that really mattered right off the bat.

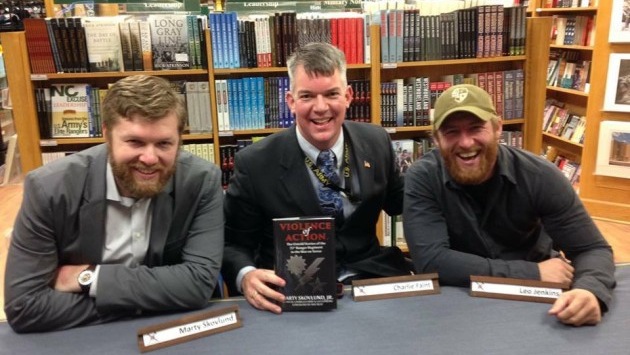

After that, I started Hit the Woodline and later, The Havok Journal, which were not meant to be Ranger-specific or even veteran-specific publications, but that is the majority of our readership as it stands today. Thanks to guys writing about their experiences with brutal honesty, lives have literally been saved. I don’t say this to brag, but rather to show how important the writing of one’s story is; there are second- and third-order effects that must be considered. Continuing down the publishing path, I helped with content edits on Leo Jenkins’ book “Lest We Forget” and started working on “Violence of Action” in early 2013.

“Violence of Action” would be the first book with my real name on it, which was terrifying. But I saw it as an opportunity to tell our story, ourselves, without a historian or outsider fucking it up. Of course, we cleared it with the 75th Ranger Regiment and went to extreme lengths to ensure OPSEC and PERSEC were not even close to being violated. I believe we were successful in that.

Like many books written by SOF veterans, it was not a boastful book, it was not meant to make us look like bad asses; it was just meant to tell our story. To tell it as accurately as the fog of war permits. To reflect positively on Regiment and the men who have served with a scroll on their shoulder. In a time of shrinking budgets, struggling to meet recruiting goals in an improving economy, former Rangers who think they are alone in their experiences and emotions, and up-and-coming Rangers and Army leaders who struggle to learn and implement lessons learned over a decade of war, I think VoA was incredibly appropriate (but I am a bit biased).

Thus, I arrive at my thesis: Veterans in general, and Rangers/SOF in particular, need to share our stories tastefully, without violating OPSEC and PERSEC, in an effort to ensure we are understood at even a basic level by the nation we serve or have served. The military-civilian gap is ever widening, and by staying silent we contribute to the problem. The worse this problem becomes, the more disconnected our nation becomes from her armed forces, and the easier it will become for our nation to haphazardly send our sons and daughters into armed conflict, or to cut benefits and training dollars.

All of this comes with a caveat, though. I still completely understand if you can’t/won’t get on board with this premise I have presented. I recently had a fellow Ranger that I was very close with explain why he would no longer be associated with me. It was like having the air knocked out of my lungs, and for a few days, it honestly made me contemplate everything that I had done. I don’t blame him; I was there, in that frame of mind once. I get it.

We all have experiences that shape who we are, and my path has led me to where I am at right now. I can’t blame someone for being who they are and thinking the way they do based on the path they traveled. But, after doing a mental layout of what I have done in the past few years and the positive things I have been able to accomplish, I am at peace with the fact that I may not be able to please everyone. But, whether you like it or not, Rangers and our other SOF brethren are going to continue coming out to tell our story.

Personally, I hope that I will continue to improve as an author. I hope that in 20 or 30 years I will have many books with my name on the cover (but not all about the military—there is more to me than just that!), and that I will be seen as a successful business owner. We’ll see what happens. I could just as easily be making your burrito at Chipotle by that time. If you are reading this, I challenge you to make your decision on what is appropriate of service members. I challenge you to distinguish between a “silent” professional and a quiet one.

Even if you don’t agree with someone writing about their experiences, at least give them credit for having the courage to put themselves out there, and for the hard work it takes to make a product that can hold up to public scrutiny. It’s not easy, trust me. But then again, anyone who has served doesn’t expect, nor want “easy.” Oh, and before you throw the OPSEC flag, look up the doctrinal definition of what OPSEC really is. You may find it’s not the same thing you were taught as a private.

COMMENTS