Editor’s Note: This article honoring these two brave men first appeared in SOFREP in September of 2016, nearly one year after the events described here. I have chosen to re-run this touching piece so a new generation of SOFREP readers may learn about these outstanding warriors who gave all. – GDM

—

First, I would like everyone to know that this is published as a free article. While SOFREP normally keeps full articles internal to subscribers, I asked that this one be available to be seen by all.

I contacted parents and friends of both Matt and Forrest to make sure it was okay to write and publish this article. Everything you see here has been approved by their families.

Matt Roland was one of my best friends. He was technically my team leader for over a year down in Florida, but our friendship transcended rank and structure. I did not have the privilege of meeting Forrest, but hearing about him from mutual friends that I have deep respect for, I can tell you that I genuinely regret not having had the chance to shake his hand and grab a beer.

One year ago, last week, Captain Matt Roland was driving his ODA team back through a vehicle checkpoint and into the interior portion of Camp Antonik, Helmand Province, Afghanistan. He’d done it a hundred times, but what made this trip a little different than the rest was SSgt Forrest Sibley sitting shotgun. Forrest had just arrived in country and was still in the process of shadowing Matt. During this handover phase, the incoming CCT generally follows the outgoing guy around- meeting contacts, figuring out where things are, driving the roads and checkpoints, etc.- for as long as possible before the “old” guy goes home.

For Forrest and Matt, this process was nothing new. Both men had deployed multiple times before to Afghanistan and Africa. Handover periods were chill. After 6 months of not seeing any of your Air Force boys, someone finally came over to visit you. It’s an exciting time. You bump into someone from a different squadron (in this case Forrest came in from North Carolina to replace Matt, who was going back to Florida) and you immediately ask each other about mutual friends, and become good friends in the process. Matt probably told Forrest where to find ice cream and good wi-fi. He probably handed over a stash of beef jerky, some protein bars, and maybe even a memory foam pad to place on top of some sagging, sad excuse of a mattress. And if I know Matt, there was probably some expensive whiskey that had been sent to him like a file in a cake, stashed away for the right moment. Forrest probably told Matt about some great spot near Pensacola where he could grab the best fish tacos and a cold cerveza before fall.

There’s a real bond formed between two men, in a foreign and hostile land, going different directions. The one showing up is grateful for the time and efforts of the one departing. The man leaving is eager to go, but also eager to catch up with his brother that just arrived in hell. He’s made an honest attempt to leave this place better than he found it, and the new guy appreciates that. Everyone that’s ever deployed remembers who came to tap them out. It’s a unique feeling. You’re super pumped that your time is almost up, but you kind of wish you could stay and get in on a couple of good missions with your bro.

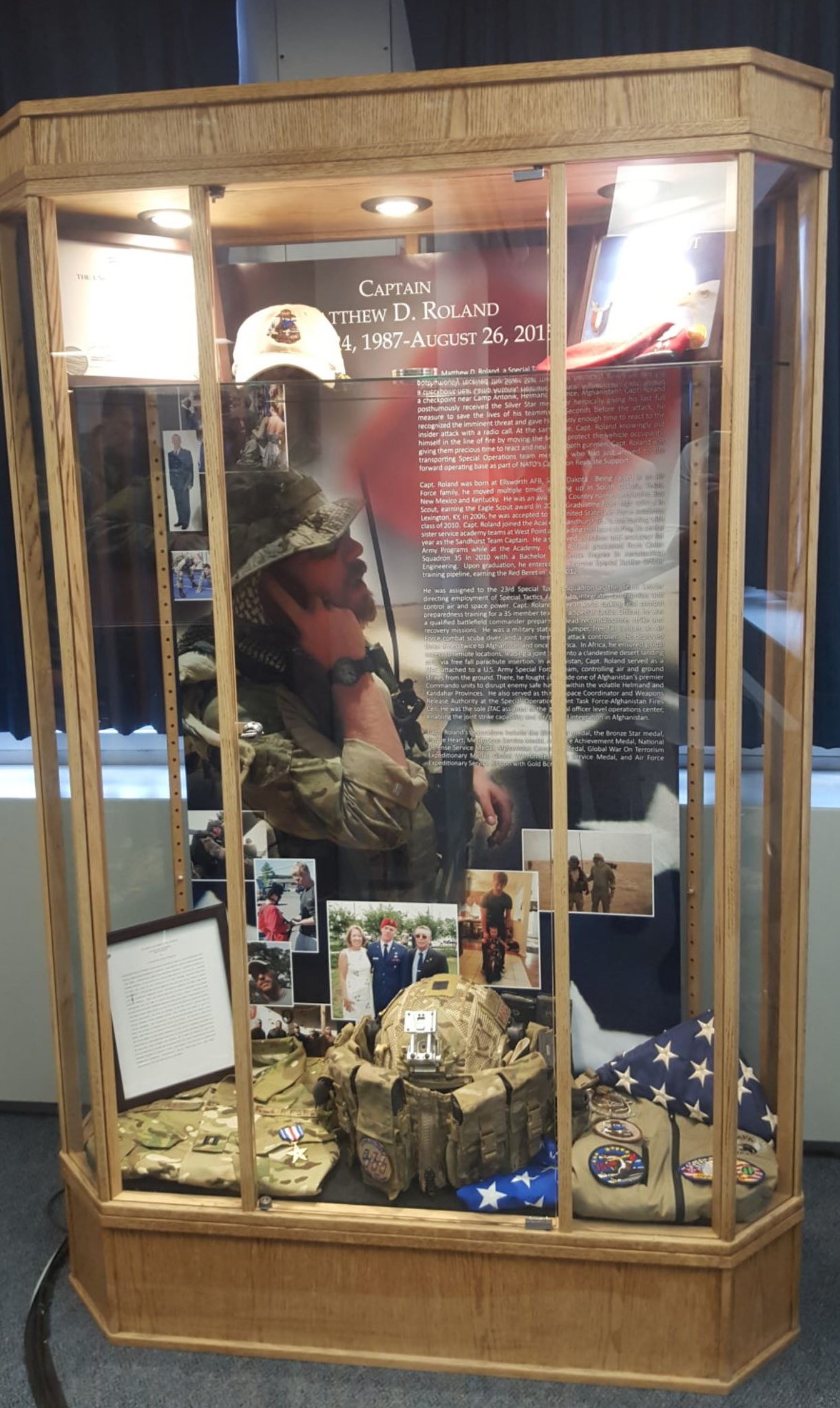

Both Matt and Forrest were dedicated professionals. Forrest had already earned 4 Bronze Stars (1 with Valor) in his first 7 years as a controller. Matt had likewise garnered countless awards and decorations during his time as a STO, team leader, and as a cadet at the Air Force Academy. But when two brothers are together, that stuff couldn’t have been further from their minds. And if they ever heard us talking about medals, they’d both quickly change the subject.

They came from different backgrounds: Matt from the nomadic life as the son of a B-52 and B-1 Navigator/Bombardier; Forrest the son of a gifted blues musician, grandson of a retired Navy WWII vet, and nephew of a retired Green Beret. And, as is so common in the CCT community, you probably could have predicted their future service to country by the time they turned 6.

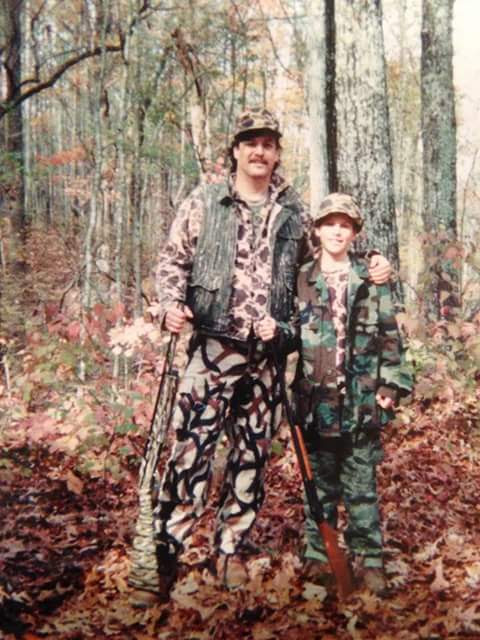

Matt was a life-long Boy Scout and loved the outdoors. His dad claims that Matt boasted he had “1000’s of miles on his hiking boots” before he was 14. He read history, studied military doctrine, and got his hands dirty. Everyone that knew Matt asked for his advice on some handyman project, but before he ever finished his dissertation of a recommendation, the person asking usually just cut him off and offered payment of a shared bottle of whiskey to have Matt complete the task instead.

Matt could always tell when it was time to stop talking, accept a drink with a friend, and get to work. People trusted Matt’s advice. And he knew so much you figured he had to be at least 50% full of crap. But I mean this when I say it: he knew everything about everything. He brewed his own beer, fixed broken water mains, and sewed the buttons back on his pants. He knew the records of college football teams, every constellation in the sky, and probably who Napoleon partied with on his 30th birthday.

Forrest was reserved, easy-going, and steadfast. And he stood for what he believed in. He grew up hunting and fishing in the woods of the Deep South. Born in Louisiana, Forrest later moved to Alabama, where he finished high school. He loved being outdoors, learning from his father and grandfather to track animals, shoot guns, and become a man.

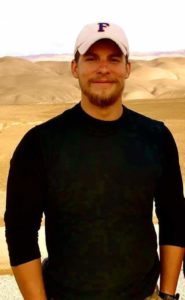

Forrest loved college football, especially the Florida Gators, and would make sure to come inside for a couple hours each Saturday to watch his team play. Forrest’s dad recounted a story about “Fo” calling him up on his first deployment. His dad had asked him what he could send over to him, and Forrest, after glancing around his plywood 5’x10′ cubby, decided that a UF rug and banner would really tie the room together. It was in the mail that afternoon.

Matt had always been a leader– and always led from the front. He knew when to step up and get his message across clearly, but he also recognized the value in listening to the ideas of everyone else on his team. Most of the time he would just be in the background, drawing absolutely no attention to himself, and preferring it that way. He was always the first to show up for something, and the last to leave.

On more than one occasion I’d drag my ass up to the locker room at 10pm, unable to sleep- certain I had forgotten to prep a key piece of equipment I’d need for the next morning’s events. As I’d rub my eyes and feel sorry for myself for having to be there so late, knowing I’d have to be up so soon, I’d hear the muffled sounds of classic rock, or maybe a little Willie Nelson coming from Matt’s cage. And there he was, with the whole team’s gear, checking and re-checking all our shit so we didn’t get crushed the next morning.

He’d have 24 sets of equipment spread out, meticulously gone over for any discrepancies, while he worked on next week’s training plans with a fat dip in his bottom lip and probably something camo ripped up and tied around his head, Rambo-style. I can still see him look up, wink at me, letting me know he’d done it all and I didn’t need to thank him. “Get some sleep, bro,” is probably what he said. “I’ve got this.”

Forrest had likewise been happiest when the limelight was on others. His Army and Air Force teammates both have told of his heroism in countless battles. From the stories told about Forrest, at least some of those Bronze Stars could’ve and should’ve been much more.

During one of his deployments, his team infilled onto a mountain range. As soon as his guys hit the ground, the whole place exploded. Rockets, gunfire, etc. It was too hot for the birds to come back and bring them out, so the team had to stay and fight. For three days, they fought and ran their way off the mountain and towards a defendable position, outnumbered at times 10-1. During the hasty initial rush to get off the mountain, Forrest tore his ACL and MCL.

So that American badass spent three days running and gunning on a blown-out knee, until he had destroyed the trailing enemy with CAS and found his guys a suitable HLZ for exfiltration. Upon his return to the FOB, he wrapped up his leg and went on every single one of the remaining missions with his boys for three more months until his rotation was up. No one was allowed to lighten his load, either. He was either going to participate fully, or not at all. They probably stapled his ligament back together with his Purple Heart and got out of his way.

Another story, directly from a fellow operator’s mouth to the family of Forrest, tells of a firefight so intense that the U.S. guys could barely get their heads above cover for even a second to return fire. The hail of bullets was withering, and everyone was pinned down with the enemy beginning to advance. The operator looked up to see Forrest, 50 yards past the nearest cover, fully exposed in order to accurately call in life-saving close air support. As he radioed to the team to take cover, he dropped multiple munitions danger-close, eliminating the threat and saving his boys.

But his family had to hear every one of those stories second-hand. Because Fo never talked about himself. The closest he’d ever come to bragging was when he would tell people that he had the best job in the world. He just loved it. He loved sky-diving, scuba diving, shooting, riding dirt bikes…but most of all he loved the guys he served with.

The night Matt and Forrest were killed, they were out late, doing what they loved. They were living and thriving in a part of the world everyone else had abandoned. The word Helmand brings both the tingling sensation of the thrill of battle and the suffocating heaviness of heartache to anyone who’s patrolled its poppy fields or waded across its icy river. That place is no joke. If you were being sent to that hell-hole in southern Afghanistan, that meant your squadron trusted your skills. That’s where the A-team goes. And I guarantee you, when Matt and Forrest found out their assignments, it could have been nowhere else.

Matt was in his last week or so of deployment, expecting to catch a ride out to rendezvous with his squadron and get back to the USA. Before Helmand, Matt had been up north in an advisory role, and hated every second of it. Advising and overseeing weren’t in his vocabulary. Leading, fighting, participating- that was more his speed. Forrest had just arrived, just over a week into his 6-month-long tour. He, like Matt, had voluntarily deployed every year since finishing training. This was their norm. There were just too many bad guys to erase.

After volunteering to drive the convoy back from the concluded airfield operations, Matt pulled the small bus up to the 3rd and final checkpoint before heading off to do some paperwork with Forrest, and hit the sack.

According to the official investigation:

The day Matt Roland was killed, he was two weeks away from finishing his six-month deployment to Afghanistan. Roland, Forrest Sibley and other members of an Army special forces team “had just finished conducting airfield operations at an unsecured landing zone” when they began the trip back to Camp Antonik.

Roland knew the road home best, so he volunteered to drive the lead vehicle. There were three Afghan-run checkpoints on the way, and they passed the first two without any trouble.

When he realized the guards at the third checkpoint had laid an ambush for them, Roland made a decision. He could have ducked behind the dashboard to save himself. He could have reached for his own weapon.

But instead of trying to protect himself, the Pentagon said, Roland acted to save his fellow troops’ lives by alerting them to the danger and trying to move the bus out of the kill zone. The first volley of gunfire “tore through the front windshield of the bus, killing Captain Roland instantly.” The gunman then shot into the bus several more times, killing Sibley and wounding some of the other troops.

Roland’s warning gave the other troops a chance to take cover and draw their own weapons and kill the first gunman, the Pentagon said. The second gunman had reached the bunker by that point and shot at the bus with his own M4. But the troops were able to kill him before he could turn the M240B machine gun on the convoy.

For his actions that night, Captain Matt Roland was awarded the Silver Star. He had selflessly and courageously analyzed the situation and bought his team precious time. By immediately and selflessly getting on his radio and throwing the bus in reverse, his last acts had cost him his life, but saved his team’s. Had he chosen to draw his weapon, potentially stopping the first attacker, his ODA team may have sat unaware for even a brief moment, enough time for the second attacker to get on the machine gun and wipe out the entire element.

Sibley, sitting shotgun and in the direct line of fire, died shielding his ODA team with his body- guys he’d only known for about a week. For years, Forrest had built a reputation as a teammate who ran toward danger to come to the aid of his friends. August 26, 2015, was no different. For both Matt and Forrest, two proven warriors, they wouldn’t have traded places with anybody, for anything.

Note: Captain Matt Roland was buried with full military honors at Arlington. He was posthumously awarded the Silver Star. SSgt Forrest Sibley was buried with full military honors at Barrancas National Cemetery in Pensacola, FL. Memorials for both men brought together hundreds of CCTs, PJs, Green Berets, and more, to honor the legacies of Matt and Forrest, and to meet their families. Both the Roland and Sibley families have asked me to express how moved they have been by all the support sent forth from the Special Tactics community.

If anyone would like to donate any amount to help support those warriors and their families who need it, both the Rolands and Sibleys have given high praise to the following organizations:

- Combat Control Association

- Special Operations Warrior Foundation

- Air Force Families Forever

- Duskin and Stephens Foundation

- USO

- Coast x Coast

All images courtesy of the Roland family, Sibley family, and the USAF.

COMMENTS