Near the conclusion of these debilitating speed-marches and just before rounding the curve up the last hill to camp, Captain Hoar would yell in his curt British brogue, ‘Straighten up, mytees! [mates!’] Get in step!’ Camp was still a mile away, and the wail of bagpipes could be heard in the distance. The kilted pipers, standing at the entrance to camp, greeted us with one of the traditional Highland tunes. This did wonders for morale. No matter how tired we were, the sound of bagpipe music sent adrenalin flowing. With tremendous pride, we marched into camp in step and with heads held high.”

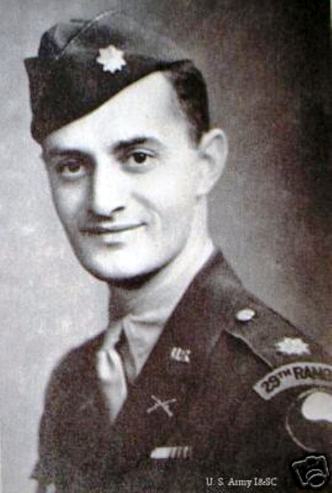

Upon graduation from Commando training, the Rangers were awarded a pair of “paratrooper” boots and a three-inch felt patch sewn on their jackets. The rainbow-shaped patch with red background and blue lettering read “29th RANGERS.”

Soon after, the newly formed Rangers were tasked with testing the Army’s new field rations while conducting a daily series of long-range movements. One company tested Army C-Rations, another tested K-rations, a third tested 10-in-1 rations, while a fourth tested the Army’s 10-in-1 rations along with chocolate D-bars. For 10 days the men averaged rucks of 25 miles a day, with the first day consisting of a 37-mile smoker.

Disagreements Over its Missions

It is here that official stories differ. Slaughter, who was in the unit from its inception until its disbanding, claimed that he had no knowledge of the battalion accompanying any British Commando raids into Norway. However, later Brigadier General (Ret.) Milholland relayed to other future officers that indeed Rangers were attached to Lord Lovat’s No. 4 Commando and that he himself participated in three raids with the British Commando Unit on the coast of Norway.

The U.S. Army put any controversy to rest, however, saying that the 29th Rangers had in fact conducted three raids on German-held territory before D-Day.

“Through the summer and fall of 1943, the 29th Ranger Battalion joined the British commandos in a series of raids on the Norwegian and French coasts. The first, an attempt to destroy a bridge over a fjord, ended in failure when the Norwegian guide dropped the magazine for his submachine gun on a concrete quay, alerting the German guards.

The Rangers met with more success in their second mission, a three-day reconnaissance of a harbor, but a third foray to the Norwegian coast proved abortive when they found that their objective, a German command post, had been abandoned.

After more amphibious training during the summer of 1943, the entire battalion landed on the Ile d’Ouessant, a small island off the Atlantic coast of Brittany, and destroyed a German radar installation. As the raiders departed, they left Milholland’s helmet and cartridge belt on the beach as calling cards.”

The 29th Ranger Battalion Was Disbanded but Kept on Giving

Nevertheless, many of the higher-ups in the chain of command rejected any notion of elite units — as some still do. So, on October 15, 1943, the 29th Ranger Battalion was deactivated and the highly trained men were all sent back to their parent units.

LTG Lesley J. McNair, the chief of Army Ground Forces preferred building versatile conventional units instead of specialized units for special operations. Permanent Ranger units, he feared, would constantly seek unprofitable secondary missions to justify their existence and absorb too many of the Army’s better junior combat leaders. These arguments would continue to be heard well into the 1980s until the Special Operations Command and the Special Forces Branch were instituted.

General George Marshall, however, listened to his field commanders and in March 1943 ordered the formation of at least one Ranger battalion to replace the 29th.

The 2nd Ranger Battalion would later storm the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc on D-Day while the 5th Rangers would take part in the assault on Omaha Beach. BG Norman “Dutch” Cota, the assistant division commander of the 29th Infantry, would utter the famous line that is now part of Ranger lore.

Major Max F. Schneider, commanding the 5th Ranger Battalion, met with General Cota while the assault infantry troops were pinned down under murderous German fire. When Schneider was asked his unit by Cota, someone yelled out “5th Rangers,” to which Cota replied, “Well then Goddammit, Rangers, lead the way!”

And the training that the officers and men of the 29th Ranger Battalion received from the British Commandos wasn’t wasted. When the green assault troops of the 29th hit the beaches in Normandy, the combination of German fire and their lack of experience would result in men freezing as soon as they hit the shore. But those Ranger veterans sprinkled among the infantry units would indeed lead the way.

COMMENTS