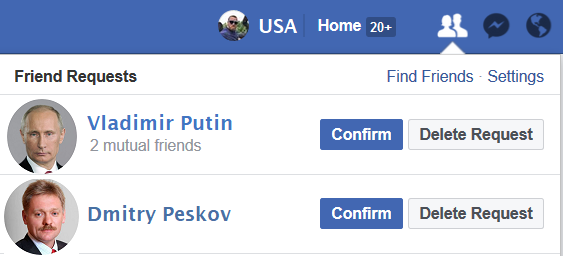

The recent revelation that Russian entities funneled money into marketing on social media platforms like Facebook in order to create dissent within the American population, particularly regarding the 2016 presidential election, has made waves on social media, and for good reason. With many Americans continuing to counter concerns about Russian meddling as either non-existent or inconsequential, the discovery that foreign interests are willing to invest millions of dollars into influencing internal politics should serve as an indicator that these practices are not only effective, but commonplace.

For those within America’s intelligence community, this wasn’t a revelation at all. We’ve been well aware of how successful these kinds of operations can be for decades. After all, we’ve done our fair share of them ourselves.

The thing about international diplomacy is that it’s always required a “do as I say, not as I do” mindset, especially when it comes to intelligence operations. Every once in a while, a story will break about a Chinese spy stealing plans for a Defense project, and we as a nation gasp as their audacity – while American intelligence agents operating all over the world shrug and wonder if it was poor trade craft or a leak that got that guy burned… hoping the same doesn’t happen to them. The common axiom, “all’s fair in love and war,” isn’t exactly right – it’s more like “all’s fair in international intel and psy-ops as long as you don’t get caught.”

The United States has been complicit in a number of high and low profile regime changes over the years, and throughout, we’ve justified those actions by using cause and effect rationale to paint a picture of justification in the interest of our own security. That isn’t anti-American sentiments creeping past my patriotic seeming exterior, it’s an honest and objective assessment of America’s foreign policy. It isn’t that we’re bad guys, it’s that, when it comes to global conflict, there are no good guys and bad guys, there can only be “us” and “them.” No matter how elevated you may feel on your moral high ground, it doesn’t actually offer a superior firing position.

Sometimes, in the interest of national security, the American government (often as a compartmentalized portion rather than as a whole) chooses to cross the lines we’ve drawn in the sand as we proclaim our moral superiority. Sometimes these are military operations, sometimes they’re propaganda campaigns, and chances are, sometimes they exist within the digital sphere… just like Russia’s. Again, it’s important to recognize that, as Americans, we see many of our own violations of international decency as a necessary ugliness, in the interest of continued American prosperity. It is, however, equally important that we appreciate that same mindset is permeating throughout the Russian government as well.

As Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, came to power in 1985, he brought with him ideas of loosening government restrictions on individual rights (an important tenant of Glasnost) and incorporating elements of capitalism into the Russian economy intended to steer it toward a more functional model like that currently employed by China. These reforms, which would ultimately lead to the end of the Soviet Union, were not just casually observed from American shores, they were ushered along by a concerted public effort, coupled with a number of undercover campaigns, initiated by Jimmy Carter and later further emboldened by President Ronald Reagan, who ran on a platform that included a strong current of anti-Soviet rhetoric.

Reagan, in particular, delivered an influx to military spending, which led to new and improved weapons platforms, capabilities, and defensive strategies. In effect, Reagan, for the first time since the start of the Cold War, saw the first significant leap ahead of Soviet military capabilities, including in America’s missile defense strategies, which meant the long-standing tradition of “mutually assured destruction” was no longer quite as assured on the American side. These advancements, coupled with a policy of economic isolation championed by the United States, led the, now far more liberated, Soviet citizenry to become extremely critical of their government.

Outside the public eye, the CIA began probing Russian defenses using aircraft that flew unannounced routes over the North Pole toward the Soviet Union or that penetrated protected airspace briefly near Asia. These flights were not written down to maintain secrecy, according to CIA documents that have since been released, and were not intended to convey any actual intentions to the Soviets. These flights, which commenced in the early days of Reagan’s administration, were for no purpose other than to unnerve Soviet defense officials as America began to take the lead in military capability. Aircraft weren’t the only ones playing this game either.

According to published accounts, the U.S. Navy played a key role in the PSYOP program after President Reagan authorized it in March 1981 to operate and exercise near maritime approaches to the USSR, in places where U.S. warships had never gone before,” the CIA states. “These exercises reportedly included secret operations that simulated surprise naval air attacks on Soviet targets.”

These behaviors, some of which seem to closely parallel recent Russian behavior around the world, were only a part of a massive coordinated effort to go to war with the Russian ideology, because actual combat operations would have been too costly, in terms of dollars and human life, to conduct. Now, as Russia works to regain its foothold as a global power, it has continued in the Cold War tradition of matching public posturing with underhanded efforts to destabilize and weaken its opponent. From our perspective, that makes them bad guys, but objectively, this is simply one facet of war’s natural progression.

So what does all this objective historical analysis really mean in the scope of today’s challenges? Certainly not that we should permit Russia to continue to work to influence American’s perceptions of their own country, president, or government. Embracing a foreign nation’s psychological campaigns would be paramount to surrender, and even politely ignoring it results in defeat, just ask Gorbachev. The intent behind this (admittedly broad stroked) jaunt back through American history also isn’t meant to point out that America is “just as bad as” anyone else, or to justify another nation’s bad behavior by comparing it to America’s own. That concept is inherently flawed, because in the grand scope of things, “bad behavior” (in terms of efforts to manipulate foreign politics) is often a matter of perspective.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Instead, the idea behind drawing a comparison between Russia’s recent efforts at election manipulation and our own history of usurping leaders with unfriendly intentions is to show that war is ongoing, even when shots aren’t being fired. Russia isn’t going to stop trying to meddle in our elections, though they’ll likely begin to adjust their methods until they find one that rests quietly below the surface of our collective perception once again. The United States isn’t going to stop anytime soon either – because doing so would leave the development of the world just outside our borders to fate, and when it comes to the wellbeing of hundreds of millions of Americans, to do so would be irresponsible.

What we need to do, as increasingly privy American people, is combat foreign influence campaigns the good old-fashioned way, while America’s defensive infrastructure continues to root them out. The intelligence game continues to thrive because the “bad guys” will continue to develop new ways to win, while our “good guys” try to figure those ways out and counter them. Back in World War II, doing your part in the war effort included buying war bonds and building a freedom garden in your yard. Today, it means looking at the crap you see on your Facebook newsfeed with a critical eye, and considering the sources they came from.

Looking back at our collective history objectively and saying, “yeah, we’ve all played this game,” might mean some may have trouble bridging the gap between their perceived American moral high ground when it comes to these types of endeavors and the reality that we’re embroiled in continual combat with another global power, just one in the communications realm rather than the physical one. Reality has a nasty way of not caring about our moral sensibilities in that regard. Likewise, we can use our understanding of history, and how successful America’s psyops campaigns were in places like the Soviet Union, to help us to better understand and counter modern foreign efforts to do the same to us.

We, as a people, may have a habit of pointing at the man in the White House, or the thousands of Americans tasked with protecting us from foreign influence as those at fault, but the real soldiers on the front lines of this fight… are us. Russian propaganda being marketed through social media only works as long we click, read, share, and believe the messages they’re sending.

Russia produces content, and pays to market it on social media – like they’re producing bullets for a gun. They’re paying up front to get the bullets to us, but that doesn’t force us to shoot them at our friends. You decide what you share. You decide what sources you trust. You can win this fight for all of us.

Modified images courtesy of Wikipedia

COMMENTS