What’s Your Trouble, USS Squalus?

At 12:55 p.m the Sculpin, the sister sub to the Squalus found her buoy and then dropped anchor. The trapped submariners’ spirits rose because they could hear the propellers above them.

Sculpin’s commander, Lt. Warren Wilkin, got on the phone. “Hello, Squalus. This is Sculpin. What’s your trouble?”

LTJG Nichols responded: “High induction open, crew’s compartment, forward and after engine rooms flooded. Not sure about after torpedo room, but could not establish communication with that compartment. Hold the phone and I will put the captain on.”

Then Naquin got on the line. “Hello, Wilkin,” replied Naquin when, suddenly, the cable snapped.

The Falcon didn’t arrive with the diving bell until early next morning, May 24. When she moored directly over the sub shortly before 10 a.m., the sky had cleared and the sun had come out.

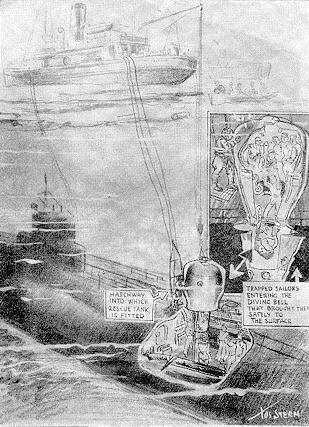

A rescue diver descended the 240 feet in the inky water to land right on top of the Squalus about three-four feet from where the diving bell needed to attach to the crew’s escape hatch. He stomped on the hatch to let the crew know he was there. The men enthusiastically banged on the hatch in response.

It took 40 minutes to lower the cable the diving bell would come down on and another 22 for the diver to attach it to the Squalus’s escape hatch. The water pressure at that depth made the simplest of tasks extremely hard to perform.

Momsen and the other rescuers were about to try tactics that had never been used before.

“Where in the Hell Are the Napkins?”

At 11:30 the diving bell was lowered from the Falcon. It took about 30 minutes for it to reach Squalus. The rescuers soon made a watertight seal on the escape hatch. The two sailors in the diving bell opened the hatch and handed down some hot soup for the USS Squalus’s crew. The sailors, never lacking sardonic humor, asked, “Where in the hell are the napkins?”

The first seven men, judged by Naquin to be the weakest, were loaded into the bell. They broke the surface just after 2 p.m. On the next trip, the sailors, knowing the unpredictable New England weather, thought to put more sailors in the bell to speed things up. Shortly after 4:00 p.m, the bell surfaced again, this time carrying nine sailors. Another nine men came up shortly before 6:30 p.m.

The fourth and final trip loaded the final eight men, including commander Naquin, into the bell. They began their ascent but around 8:15 p.m. at 160 feet, the bell stopped. The wire was fouled so they were forced to cut it and let the bell go to the bottom where they’d reattach a cable. Finally, the crew was able to lift the diving bell up. That last trip taking four and a half hours. All 33 survivors made it to the Falcon and safety.

A Historic Success

Through the display of amazing courage and intrepidity of everyone involved the operation was a success.

On July 30, 1939, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Arthur Fiedler, performed a memorial concert for the USS Squalus victims at Little Boar’s Head in North Hampton, NH. The concert was broadcast nationally.

For their actions during the operation, four officers and men would receive the Medal of Honor, 46 others decorated with the Navy Cross, and one awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

In September 1939, the Navy was able to raise USS Squalus off the ocean floor. It recovered the bodies of 25 of the 26 sailors who had drowned; one sailor had made it out of the sub but never made it to the surface. His body was never recovered.

In 1940, USS Squalus has recommissioned as USS Sailfish and served in World War II sinking seven enemy ships. Her conning tower resides in Portsmouth Navy Shipyard as a memorial for sailors lost in combat.

COMMENTS