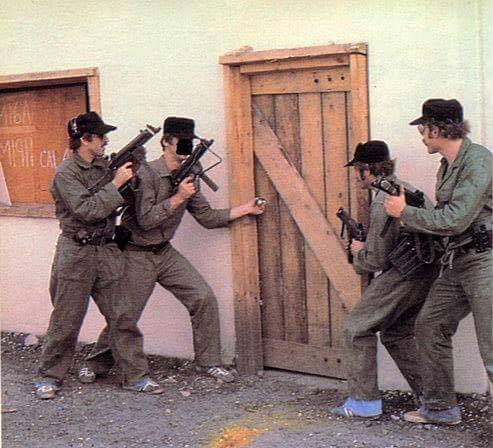

Another precarious situation unfolded when three Det A members were rolled up in the British sector of Berlin. In 1974, a training mission was devised between Det A and the Berlin Police Counter-Terrorism Unit, which would test Det A’s capability to conduct sabotage operations and the German police’s ability to respond. The Special Forces men were to attack a local waterworks, but the scenario was canned as the Germans knew the Det A men were coming and snuck police officers into the facility. A battle with blank fire ensued and Det A was repelled from the water plant. Another Det A element in a nearby ambush position decided to withdraw as the mission was compromised.

“As we [were pulling] our little red Fiat out of its hiding place in the woods, two VW buses full of the Berlin Polizei came upon us and began to chase us,” Staff Sergeant Bob Mitchell described. The three Det A soldiers got trapped in a cul-de-sac next to the British officers’ housing complex and engaged in a mock firefight with blanks against the Germans, but the Americans were overwhelmed and captured. The British provost-marshal witnessed the entire episode and believed that the Americans were British officers and that the black-clad German policemen were members of the IRA. Heavily armed British military police showed up, but by some miracle did not kill anyone — soon realizing that it was just a training mission.

“The provost marshal was so pissed that he had us all arrested and taken to the Olympic stadium to be put in jail,” Mitchell said. “Eventually, the commanding officer of Berlin, who was a three-star general, had to officially apologize to the Brits so that we could be released.” The incident was also reported in the local media that described the sabotage training and subsequent simulated firefight. One newspaper joked: “For the first time in war history, the British have ended a battle between Germans and Americans.”

At times Det A was also tasked by the CIA to dig up old caches in Germany left over from World War II. They discovered weapons, food, and ammunition, as well as medical supplies that needed to be replaced since they were well past their expiration date. Some caches could not be accessed because the Germans had built gas stations or other buildings over them. In other instances, Det A would bury caches at the direction of other parties. “It was a ruse,” Wild said, describing one technique used. “We would erect tents, usually a GP medium, put up barbed wire and telephone lines, making it look like it was a company headquarters. We would stay there for a few days, making it look like it was an exercise, but we were digging a hole under the tent to bury the cache. After we were done it would look just the same as when we got there.”

Tradecraft was also a challenge in a city packed full of foreign espionage agents and a citizenry that lived in a constant state of tension. “I have never seen a city so contaminated with load signals,” Warner Farr remarked. A load signal is a sign left in a public place that an intelligence handler leaves for his asset to see when walking past it later. It signals a meeting at a prearranged location. “When we would go to set up a drop, it was hard to find a place to mark because every damn pole in the city had marks all over it.” To avoid confusion, Farr would use circular paper reinforcements that he would stick on a wall or other surface, since they were distinctive next to the dozens of chalk marks left by other spies in Berlin.

Clandestine communications via radio were among the most difficult tasks Det A had to manage in Berlin. Antennas had to be camouflaged and disguised in an urban environment, sometimes even rigged inside buses or cars. While staying in a hotel, Gerald “Paco” Fontana of Team Six set up a 109 radio to send Morse Code, grounding the radio to two water pipes. “As I started sending Morse Code, all the lights in the hotel were flashing the code that I was sending,” Fontana said. The radio was sucking up enough power to dim the lights. The team quickly left and hotel rooms were not used as safe houses afterward.

Under the Four Powers Agreement, there were not to be any elite troops stationed in Berlin, but of course, the British Special Air Service, U.S. Special Forces, and the Soviet Spetsnaz were all present. “It was known within our circles, but officially we were not there,” Charest said. Ironically, the Spetsnaz element in East Germany probably had the same mission as Det A: to act as a stay-behind unit to conduct sabotage operations if NATO ever decided to charge across the steppes towards Moscow.

The Four Powers Agreement also stipulated that Russian and American troops could cross into each other’s territory if under supervision and in uniform. Det A members did this regularly, wearing class A uniforms with conventional Army shoulder sleeve insignias. Wild said that, during the late 1950s, “almost every day someone from the detachment went to East Germany from Checkpoint Charlie in a staff car driven by an MP and accompanied by a staff officer.” They had a very specific route to drive from which they could not deviate.

By the 1970s, Det A members could get out in East Germany and walk around while in uniform. Since the dollar had such a great exchange rate in East Germany, the Special Forces soldiers would take the opportunity to eat a gourmet meal for just a couple of bucks.

When asked about the infamous East German Stasi police, Warner Farr laughed and said, “We used to have lunch with them. There was a restaurant in East Berlin, called Ganymed, next to a canal. It was renowned for being the Stasi place.” On one visit the Stasi sat at a table next to the Special Forces men, loudly complaining that the Americans would come to East Berlin and consume all of the good food and wine. One of the Det A team leaders named Wolfgang Gartner stood up, turned around, clicked his heels, and said, “Gentlemen, let me introduce myself. My name is Wolfgang Gartner, I was born three blocks from here, and I will eat here any time I damn well please.”

While in East Berlin, the Green Berets cased their targets, knowing that they were being watched by the Stasi and Russian KGB. A few Det A members even infiltrated into East Berlin wearing civilian clothes, using the public transportation system, seeing how far they could push their limitations. In East Germany, they were usually followed and under surveillance. They would have to act as if everything were normal and behave like they were just G.I.s making a run over to East Berlin to take advantage of the low exchange rate to buy goods that would be expensive on the other side of the wall. Back in West Germany, there were enemy agents watching them parachute onto drop zones for training, keeping watch over Andrews Barracks, and occasionally tailing them around the city.

Continued in part III.

Editor’s note: This article was written by Jack Murphy and published in 2017.

COMMENTS