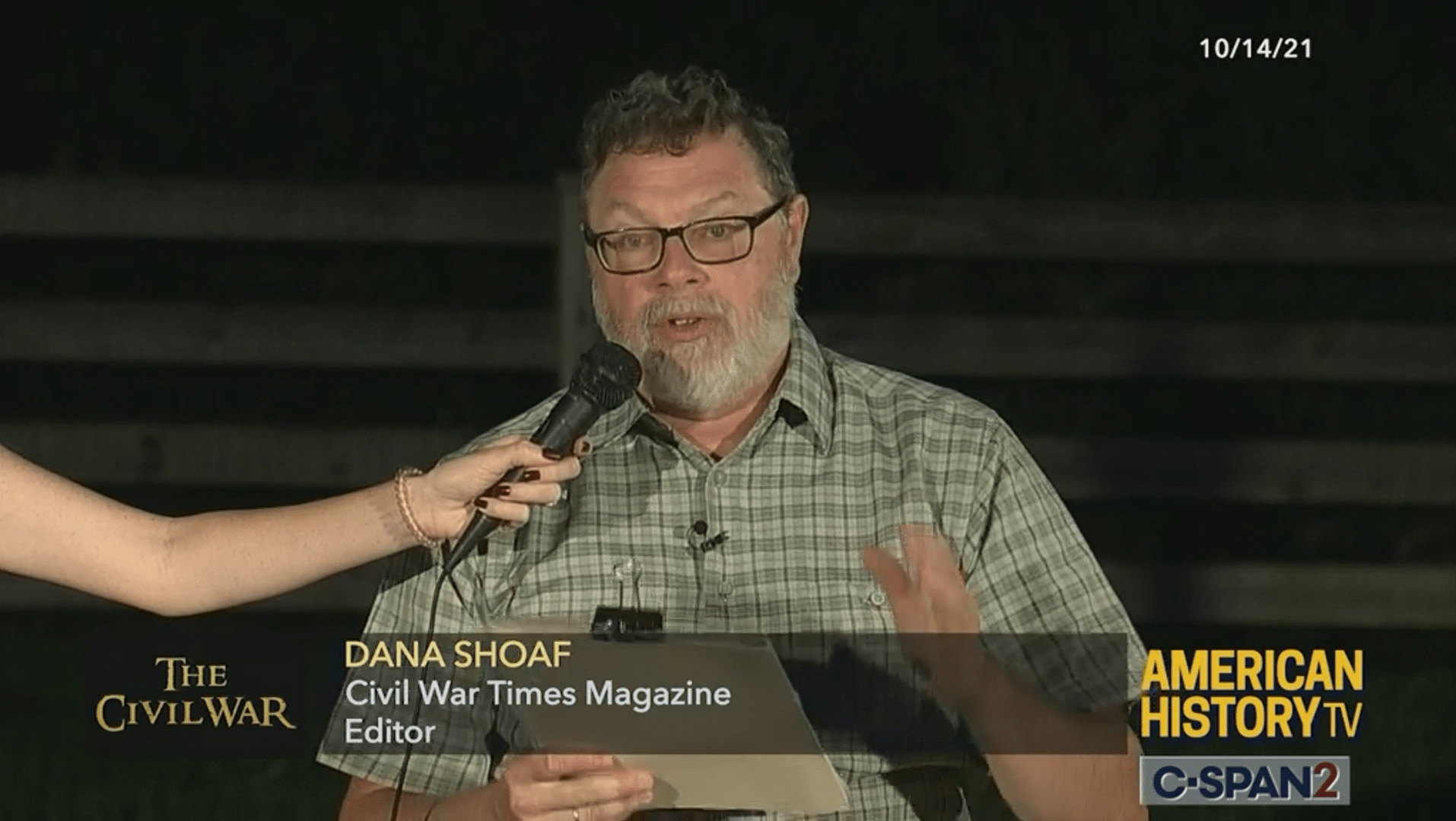

Like Dana Shoaf, historian and editor of the Civil War Times Magazine found Nevin’s diary at the John Hines Regional History Center in Pittsburgh, Elijah V. White, a Confederate cavalry officer, stumbled upon the lost Union soldier by chance.

Purely By Chance

John I. Nevin was a 28-year-old teacher in Sewickley, Pennsylvania, when the Civil War began. He enlisted in the Union Army and was commissioned in the 28th Pennsylvania Volunteers Regiment as a Second Lieutenant under General John W. Geary earlier in the war. As he goes through the uncertainties of 1861, the former Pittsburgh newspaper editor keeps a diary of his experiences. Unfortunately, some of his entries were missing. However, a good chunk of the intact pages was about his service during the war.

Very early in the war, Nevin was among the soldiers tasked with going to Loudoun County, where they would march down Leesburg Waterford to surveil the area. When they were ordered to move, Nevin was unfortunately sick. So he remained behind at a house in Harpers Ferry. Nevin decided to drag himself out of bed the next day and follow his regiment, feeling annoyed about being left behind—plus the fact that he didn’t want to miss the war.

He could not find his comrades as he ascended to the summit and described the eerie silence around him as “that warlike had passed.” He later confessed in the pages that he was lost.

“The Leesburg Valley lay peaceful and still in the bright warm sunshine that I now felt certain that I had for some time suspected that I had lost my way. Yet, I felt but little concern. We had not met any of the enemies since we had crossed (Harpers Ferry) upon the pontoon bridge that now stretched like a thread across the bright Potomac. Our pickets extended far beyond the spot where I stood. Over the valley I had quitted and our detachment was going into. I could look back and see other detachments in Harper’s Ferry, like thin black threads marching into the town. I sat down on a large rock to rest for a few moments and consider what to do.”

Shoaf explained that at this point, Nevin had already become a sort of tourist who sat over the rocks, admiring the view.

Nevin continued: “How glorious it did seem to me. What a moral sublimity was added to the natural beauty of the scene. The Yankee army was still marching into the town caring with it what destinies? What terrible errands? What consequences to reach the enemy? Who can tell even at this moment? The bright sunlight glances fitfully back from the burnished bayonets of some regiment as it crosses that black thread of a bridge while the mellow strain of its band faintly fills the air.”

Unfortunately, the moment of tranquility of this lone soldier abruptly changed when he heard a rustling noise and “saw men in some coarse gray overcoats with Sharps carbines in their hands.” He was so enraptured with the view, as well as lost in his thoughts, that by the time he noticed the enemies, it was too late for him to escape.

COMMENTS

There are 0 Comments on this article.

You must become a subscriber or login to view or post comments on this article.